Sandra Lee Eula: Two Waters (Seeds in a Wild Garden)

It's an April day, actually Palm Sunday, and my mind is on how the warm sun and cool air meet on the surface of my skin, creating a brew of sentimental storm of dawn and departure. The morning's gauzy mist lifted to reveal lines--lines from my window panes, yellow lane dividers, disappearing train tracks, and sinuous subway lines that deliver me to the Brooklyn Botanic Garden's front step to witness artist Sandra Eula Lee’s Two Waters (Seeds in a Wild Garden).

When I arrive, Lee escorts me through a side entrance zigzagging through a swarm of visitors. Wearied by the endless winter, the drowsy crowd reminds me of cicadas abandoning their molted shells, emerging from their dark tunnels finally to serenade the spring and summer. Everyone's skin appears tickled pink, perfectly content under the canopy of the cherry blossoms and magnolias in bloom. We enter the sultry-aired Tropical Pavilion and then again descend into the Steinhardt Gallery, which even though underground is full of light. Right away I notice one of Lee's sculptures, the one to the far left, in the sunken center of the space, because it too is radiating a puff of light. I force myself to ignore it and begin my walkabout at the wall. Lee leaves me as I launch into a journey with her thoughts through garden photographs of Korea, China, and the United States.

These garden images are not your typical Town & Country spreads of sculpted topiaries, lush lawns, and dreamy flower beds; they are edgy and editorial in a way that make you look deeper before flipping the glossy page. The photos are contemporary and yet at times feel vintage, some of a few decades past, and others centuries old. Taken just a year or two ago on her travels in Korea and China, ironically it is the lines that give away the photos' age. These are different lines – not laugh lines, wrinkles, or crow's feet that come with life experience; rather, these lines are of a new generation and appear in the background in the form of scaffolds, construction fencing, and truck routes. Simultaneously, these lines communicate connection and interruption, development and destruction.

In the first photo, "View from Busosan, Korea," taken in 2010, Lee expresses this dual epoch-like quality by visually slicing the photo in half, with the top portion in color and the bottom in black and white. It takes my eyes a few moments to notice this and when I finally do realize the dissection, my curiosity is piqued. I need to know more about this location. From atop a hill, Lee captures a frame that includes an unknown male figure slightly slumped over a pier hovering over a body of water. He is faceless, but the contours of his back read like a broken asana pose, tense and pensive as he stares from this seemingly serene point of nature across to a construction site of yellow trucks, dirt roads, and cleared land. A clash of color, sound, and culture create a harmonious composition; the water separates and connects bodies but also holds and carries sprawling emotions.

Adjacent to this photo, spilling out from the corner of the wall onto the floor, is a pile of vibrant green rocks and rubble Lee collected from construction sites during her trips overseas. Tucked within the airspaces, Lee fits green rubber gloves, tubes, wire, and glass, building upon the concrete mass and softening the landscape. Sparingly scattered on top like confetti are pink, yellow, orange, and blue nails resembling wildflowers in a meadow. While traveling abroad and living in New York City, Lee began to notice a cross-cultural behavioral pattern – a need to paint things green to mimic nature. This piece, entitled “Seeds in a Wild Garden,” is actually Lee's starting point of the exhibition. Hand-selecting these rocks and debris, collecting them, traveling with them, laboring over the pieces, composing and then deconstructing the materials, Lee's process is one of a true gardener while at the same time redefining the concept of the garden.

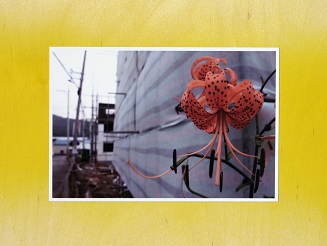

A collection of photos along a yellow horizon line continues this concept of encountering nature in unexpected places but placed with intention. Simple images of a temple plant in its own sacred space in a square container and circular opening become complicated thoughts of earth and heaven. Circular vignettes of potted plants around a concrete column in the middle of a sidewalk in China intermingled with graffiti and street signs and more containers in between clothes lines of intimates become just as powerful as the temple plant. One photo of a spotted tiger lily with its petals arched completely open exposes its curled stamen wanting to give life to its barren environment. Even though the flower is small in comparison to its blurred urban background, its purpose is clear. The Pursuing the Horizon series ends with a photo of a mother and child looking out from a pier into reflections of trees and sky in the water.

I move toward the sunken center of the room that holds three architectural models Lee has composed, again out of collected construction materials. I feel like the figures in Lee’s landscape photos, gazing at what is being constructed from a distance. The railings around the space separate me from these three floating pavilions and I become the viewer from the outside rather than inside. Each structure is unique and indicative of native land.

After viewing the exhibition I make my way back to Lee and ask her to tell me more about the first photo that is cut half in color and half black and white. "Where is this?"I ask her. She explains that it is a historic site in South Korea and goes on to explain that it is not so much the history of why she photographed the site but of the encroaching construction on the this natural site. The Korean government has mandated a controversial $20 billion restoration project known as "Cleaning the Water"to supply clean water and stimulate recreational opportunities along the river. But the public responded with anger and opposition because they saw it more as a business scheme and propaganda to build a canal that would destroy the natural rivers. I still needed to know more of what happened here and why it was historic. "This site has a postwar legacy that after the Third Battle, the Korean royal kingdoms had come to an end. The maidens had no hope and nothing to live for because of the defeat so they jumped to their deaths from this pier into the river. It represents the end of the royal lines."I think back to the tiger lily and how it understood its existence.

Before leaving the gardens, Lee asks if I have time to walk to the Japanese Garden. Out into the spring day strolling with the crowd, I ask Lee about her family. She tells me of her Korean heritage and how initially she had travelled to Korea to learn more of her family history and try to connect with relatives that had been lost and unknown to her. We share immigration stories and walk through the Japanese tea house to look out over the pond and hills with blooming azalea and cherries. Lee shares some history of the garden’s design and how a few elements, such as the gate, are not so traditional because it was constructed by immigrant laborers who interpreted the landscape through different lenses. Reflecting ourselves, the landscape lines change and our need to relate to what surrounds us becomes stronger as we struggle to survive. Even under the most difficult conditions, it becomes an urgent task to create a garden.

Sandra Eula Lee's exhibit has traveled from China to New York and will be back at its starting point in Seoul, Korea in June at the Alternative Space Pool.