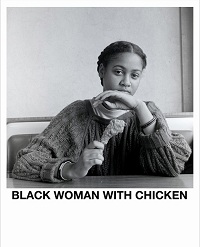

It happens quickly -- discomfort in a public place -- and it is a very effective element to control, as you will experience with the work of Carrie Mae Weems. Early on in the exhibition at the Frist Center for the Visual Arts, Carrie Mae Weems: Three Decades of Photography and Video, Weems confronts her audience with her AINT JOKIN’ series from 1987-88. Here she combines images and text that project racial stereotyping with works such as "Black Woman with Chicken" [left] and "Black Man Holding Watermelon." In another piece nearby we see a vintagepolitical drawing of Abraham Lincoln looking a bit disheveled, seated in a room filled with props and papers positioned above the question: WHAT DID LINCOLN SAY AFTER A DRINKING BOUT?. The answer-box nearby reveals: I FREED THE WHAT?. The exposure to this, and other bits of appropriated hurtful humor will surely prompt an uncomfortable feeling in most viewers as it flies in the face of current, 'public' trends toward universal political correctness.

On an opposite wall in this same first room are Weems's FAMILY PICTURES AND STORIES (1978-84), which shows, through photographs and an audio track by the artist, her nuclear and extended families as they raise children, work, gather for an extended family photo, or just have fun in her hometown of Portland, Oregon. This juxtaposition of these first two series mentioned above is not coincidental, as the starkly contrasting worlds of perception and reality meet to represent this physical and psychological battleground.

CONSTRUCTING HISTORY: A REQUIEM TO MARK THE MOMENT (2008) records staged reenactments, with Atlanta residents and Weems's Savannah College of Art and Design students. The resulting photographs, which mimic life-changing events ranging from the assassinations of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King to the death of one of the four Kent State students, are set in an interior space that includes lighting stands, camera tracks and black-out fabrics in the picture plane. One would assume that Weems is opting for a more Surreal or dreamlike statement that for one, evokes the initial disbelief many of us felt as the knowledge of such horrible events originally worked their way into our daily lives. It's that feeling of the initial shock tempered by disbelief that is more precisely what is at play here.

Cornered (2012), which consists of two video screens that converge in one corner of a room, shows two lines of protest made up of pro and con de-segregationists responding to Boston's 1965 Racial Imbalance Act. On each side is one key figure that taunts the other with stare-downs and dares. The only sound is Samuel Barber’s "Adagio for Strings," which greatly enhances the viewer’s already heightened alarm. Since you cannot hear what they are saying, you are left to imagine their words and thoughts, making this gut-wrenching scene even more turbulent.

Also in the same room is the series SLOW FADE TO BLACK (2010-11), which depicts out-of-focus images of African American women of stage and screen, an homage to the stars who once inhabited the front lines of the entertainment field such as Nina Simone and Josephine Baker -- two of the many great personalities that now are lost in our collective memories.

On an opposite wall hang two stunning photographs printed in a tondo format of children enjoying simple pleasures as their minds fill with daydreams. May Flowers and After Manet are from the MAY DAYS LONG FORGOTTEN series taken in 2002, and they show Weems’s strength when it comes to photographic richness and flawless composition. Just beyond these two works is the entrance to a room that holds the series FROM HERE I SAW WHAT HAPPENED AND I CRIED (1995-96). All of the photographs here are appropriated, and were originally intended to depict the pictorial profiles that supported the basis of racism back in the day. The text, phrases such as YOU BECAME A SCIENTIFIC PROFILE, A NEGROID TYPE, AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL DEBATE, and & A PHOTOGRAPHIC SUBJECT that Weems has etched into the glass gives each subject some form of identity, and in doing so, restores a modicum of dignity. The rest is a nearly unbearable reminder of a past covered with the blood and sweat of the people these photographs attempt to represent.

It is important to note that this is Carrie Mae Weems's first major museum retrospective -- an exhibition long overdue -- and the Frist Center for the Visual Arts should be commended for taking the initiative, for doing the hard work of amassing the art, and for so respectfully mounting such an important exhibition of one of our most important living American artists. Carrie Mae Weems: Three Decades of Photography and Video ends on January 13, 2013.

Elsewhere in Nashville

The backbone of Nashville’s art scene is its impressive not-for-profit spaces. In addition to the Frist Center for the Visual Arts there are the Tennessee State Museum, which I did not get over to see this time around, the Cheekwood Botanical Garden and Museum of Art, the Parthenon and the Carl Van Vechten Galleries at Fisk University.

The Parthenon in Nashville was built as the centerpiece of the Tennessee Centennial Exposition in 1897. It now stands, having been rebuilt in the 1920s and '30s with more permanent materials, as the lone structure in Centennial Park. Today, it primarily functions as a museum, featuring a permanent collection of 19th and early 20th century American paintings that were donated to the museum by James M. Cowan. One of my favorites here, Winslow Homer's "Rab and the Girls" (1875 [right]), is beautifully executed using ever so slight touches of paint that suggest hints of surface texture. This technique, combined with the casual immediacy of the composition hints at the future American Social realist painters of the 1920s, '30s, and '40s. Another is Elliot Daingerfield’s "Leda and the Swan" (n.d.), which is executed with strategically placed shimmering touches of paint. In looking at this piece, I am immediately reminded of the magic achieved by another great symbolist painter, Odilon Redon. Another popular attraction at the museum is the monumental sculpture of Athena, a 42-foot tall, mostly gold-covered statue that is as true to the lost original from Athens, Greece, as scholarly conjecture will allow.

Cheekwood Botanical Garden and Museum of Art is the former home of Nashville's Cheek Family, developers of Maxwell House Coffee. Today, Cheekwood holds a number of great works of art. One room of the museum is dedicated to Nashville native Red Grooms, and features the whimsical and willowy mixed media installation Mr. and Mr. Rembrandt (1971). Most important is the room

dedicated to the sculptures of William Edmondson. Edmonson was the quintessential outsider. Never having learned to read or write, he lived a life filled with manual labor jobs and quiet bachelorhood. In the mid-1930s, and fifteen years before his death in 1951, Edmondson claims he was commanded by God to begin creating tombstones for his people. Using Tennessee limestone, he proceeded to carve works such as the mindfully, albeit awkwardly proportioned "Eve" (c. 1936), the playfully simple pairing of "Bess and Joe" (c. 1935), and the incredibly Modernist minimal abstraction "Critter" (n.d. [left]) -- a group of works of art that I will likely never forget. Another unforgettable aspect of Cheekwood is the incredible vista that overlooks the gardens.

Over at the Carl Van Vechten Galleries at Fisk University is The Alfred Stieglitz Collection of Modern American and European Art. The four pieces that stand out in this sea of great art are: Diego Rivera's "Le Sucrier et les Bougies"(Sugar Bowl and Candles) (1915) -- a rare and most profound nod to Cubism by the artist; George Grosz's "Street Scene" (1933-34) -- where the artist employs a wet on wet watercolor technique that remains fresh and fluid as the day it was painted; "Red Tree and Sun" (1929), an oil painting by Arthur Dove that reveals an atmospheric fracture and a gray black sun, a vision that one might experience right before losing consciousness; and finally, Marsden Hartley's oil on canvas titled "Landscape #19" (1909), which features swirls and scrapes of color that abruptly adjust the natural forms of land and sky, and where a tree bends its limbs downward as if to say "Marsden, we give up, we are moved by your vision and we bend to your will."

Nashville -- it's not just great music.

Image info:

Carrie Mae Weems. Black Woman with Chicken from Ain't Jokin', 1987-88. Gelatin silver print, 20 x 16 in. International Center of Photography, New York, Gift of Julie Ault, 62.2001. © Carrie Mae Weems

Winslow Homer, Rab and the Girls (1875), oil on canvas; photo credit: Gary Layda

William Edmondson, Critter, Limestone, Museum acquisition by Cheekwood Collector's Group