After ten years in New York, Pia Lindman is experimenting with community building and constructing a sustainable and poison-free house in a small village in Finland. Her practice is moving further toward workshops and collaborations and engages with questions of health and individual as well as collective bodies. Last August, she started as Professor of Site and Situation Specific Art at the Finnish Academy of Fine Art -- an opportunity to develop further her ideas of art as workshops and research.

Bradley Rubenstein: Tell me a little more about your background. I know you have moved around a lot. Where are you originally from? What made you decide to become an artist?

Pia Lindman: I am originally from Finland. After high school I studied architecture in Helsinki, and in six months I realized that neither my fellow students nor the professors were concerned with making environments more livable or with simply facilitating happiness. I switched to fine arts, thinking naïvely that I could share these goals with artists. Now, after a few years of experience, I realize I cannot "build" happiness and then impose it onto people. I am still concerned, though. So, I try to be in dialog with other people, to understand what I can facilitate -- more dialog, I guess. I have also found artists and architects who are concerned with the same things that I am. Thus far, I have chosen to continue to function as an artist rather than an architect, because I feel I have more free range as to what I can do.

BR: You have worked in the United States and Germany for many years now. Do you still think of yourself as a Finnish artist?

PL: This is a complex question. If with Finnish artist you understand the common stereotype often promoted by Finnish cultural personalities and institutions themselves as THE "Finnish" artist -- one that finds inspiration solely in (Finnish) nature and his or her own subjectivity – then I am not a Finnish artist. However, my ethical grounding for any work that I do has clear connections to me growing up in Finland. Growing up in Finland can mean a lot of things, also things that are similar to someone growing up in another part of the world. So, even though I experience my background as particularly Finnish, I do not think that "Finnishness" is a unique condition or propensity. Yet, I have a knowledge and sensibility that originates from there.

Another stereotype about Finland that Finns like to define themselves by is in design and architecture: the purity and beauty of the pristine Finnish nature is reflected in Finnish design and architecture. The natural purity of Finnish form makes the design livable and beautiful for everyone. This is why Finnish design is so world-renowned.

I spent many years struggling with issues of aesthetics and ethics -- building an argument for my own approach, which is based in social context and interaction. My own naïveté in the beginning of my architectural studies reflected the utopian ideas of purity and beauty purported in Finnish design and architectural discourse since the turn of the century. My reactions against this discourse, as well as my own initial naïvety, have been formative for my art practice.

BR: You seem to have moved from pieces that focus on yourself and your body to works that are primarily about social constructs and relationships. Is this a fair assessment? Why this direction?

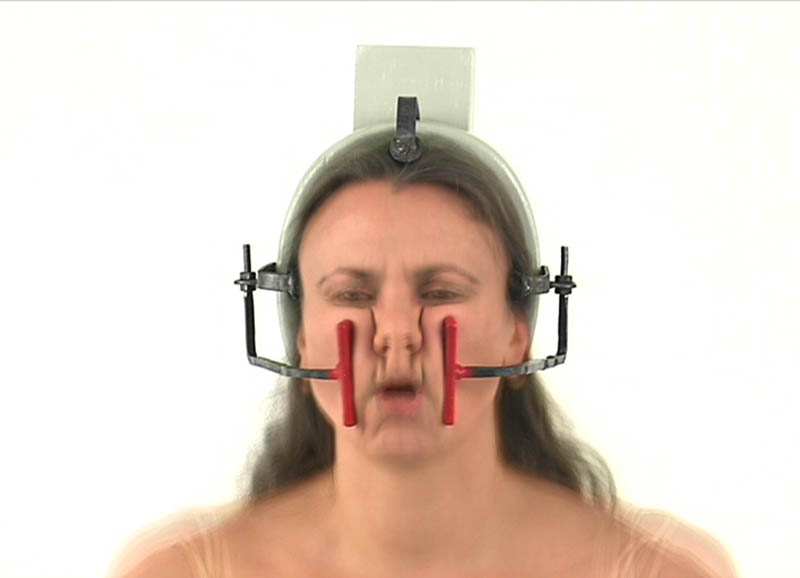

PL: Before, I moved toward work that involved the audience in my "events," rather than just me performing. There was a time for me when I sorted out my take on feminism. This is why in my art I focused on my body, partly as a cultural artifact and partly as a tool or organism over which I could take command. I was looking for ways through my body to alter cultural codes. This bodily investigation has been another important part of the grounding of my current work. Assessing the importance of culture in human interaction, I also realized that architecture participates in giving the premises for this interaction. So, it has been clear to me since then that my work situates itself in the intersection of architecture, social context, and culture. The form follows this equation.

BR: Some of your work involves an investigation into the relationships of different cultures to physical hygiene. What is it about this subject that interests you?

PL: Body and gender politics for one. Even more than just that, I am interested in how these politics are played out in spatial arrangements -- architecture. Also, politics of leisure and pleasure interest me. They are always part of our cultures of corporeality.

BR: As a painter I am reasonably aware of when one of my paintings is finished -- either it looks like what I had in mind, or I stumble upon an image that I find interesting enough. Your work usually involves constructing an object of some sort, then there is an activity or performative element, and then sometimes the piece lasts for months during an exhibition. When is it "done" for you? Is that even important?

PL: Usually, when I start working on a site -- that can be a social situation, or a specific place, or both -- I do a lot of background research. I find out what discourses about the site or in the site would be something I want to work on. It is important to me to decide to realize a project under the specific conceptual premises that I work out. That is the beginning. The ending may or may not be defined. For my mental health, it is sometimes good to close a chapter, but it may not be necessary for the piece itself.

I engage and live somewhere, and that will always result in learning about that place. Oftentimes, it will also lead to projects. I learned about Joyce Kilmer Park on Grand Concourse in the South Bronx because I participated in the AIM seminar at the Bronx Museum of the Arts, visiting the museum and park weekly. That is why I decided to do a piece there, relating to the specific situation in the park. Of course, making a piece is a continuous learning process regarding the place.

BR: You made the Mastress project in an investigation into sexual practice -- more or less an attempt to find a tool for better girl-on-top sex; and your Hybrid Sauna was your attempt at recreating a traditional Finnish bath in the United States. Is a component of your work an attempt to build something for yourself because of a personal interest that then turns into something larger in scope or concept?

PL: I have to have a personal relationship to the site or situation that I am working with. Taking my point of departure in my personal reactions, I develop concepts further in an effort to engage a larger context, before I actually take the step to realize something.

BR: We have talked about books and literature before. I know you like to read a lot. Have you read anything of particular interest to you lately?

PL: While on vacation in Finland this summer, I read a novel titled Minä, Olli ja Orvokki by a Finnish author, Hannu Salama. Hannu Salama wrote this book in 1967, after he had served a year in prison for his earlier book Midsummer Dance. He had been sentenced to prison for blasphemy. Both novels contain some swear words and snappy remarks about God, but what must have been most difficult to swallow for many Finns at that time was his direct depiction of the life and bitter sentiments of the disempowered working class in Tampere. Minä, Olli ja Orvokki has a crude atmosphere of acerbic class war, including a devastating Civil War. It is an atmosphere I recognize from my childhood and growing up. I think about it now as a traumatic social condition in which bloody murder was hushed up by a whole community, in shame of murder ever having been possible. What affected me the most in the novel, however, was the pervasiveness of a macho culture embedded in Finnish society in the form of alcoholism and misogyny. I wonder how much this machismo must be part and parcel of the trauma. Reading this book reminded me of my past as part of a society with its own specific past. It was insightful but painful.

Currently, I am reading Margaret Atwood's After the Flood. I have just bought an old farm in the South of Finland together with some friends, and we have started to build an ecological village. Fully aware of the risks involved in an enterprise such as this -- that is, forming a company with friends, building together, sharing an ideology about sustainable living, and community building -- I thought I should learn from Atwood, who seems to have mapped out some of the pitfalls.

BR: What usually inspires a new idea for you?

PL: For instance, reading Salama or Sassen and pondering over the issues they bring forward to me causes the accumulation of a body of knowledge, including emotional knowledge. Of course, the knowledge builds up in various ways: lived experience, news, other peoples' accounts, or simply observations. When I have a site, that is something more specific to attach this knowledge to, I will start having ideas. A site may come to my attention by my own accord or by someone else. Many times an institution invites me to do something on premises defined by them. I do a lot of research about the premises, and I usually find a site there that I can relate to.

BR: After Public Sauna you created an exchange program for museum guards. Can you tell me a little more about it?

PL: I worked a year at P.S.1, earning minimum wage guarding my own piece there, Public Sauna. During this time, I came to know many of the guards there. I noticed how the specific culture of guarding varies from country to country, even museum to museum.

Cultural exchange usually is a privilege of the educated classes. Cultural exchange among the working class seldom happens other than as a necessity, which is the result of displacement by labor markets. Yet, cultural exchange among academia is quite free of radical renegotiations. The languages of academia are usually shared among educated people. Knowledge and ethical standpoints, however different, are still usually based on certain shared premises. Talk of a harmonious global village is a redundant dream as long as we only promote cultural exchange on the levels of academia.

BR: Along the same lines, it seems that your teaching has taken a more forward position in your activities. Can you talk a little about that as well as what role it has in your work as a whole?

PL: Ever since the first sauna projects (Hybrid Sauna in Cambridge, MA, 1999, and Public Sauna in New York, 2000) my work has often taken on forms resembling workshops. With Poison and Play I worked specifically with the idea of workshop as an artwork. Hence, for instance, Lazy Climbers, a workshop I created together with an acrobat, Katja Echterbecker, to teach adults to climb trees.

In August 2011 I started as Professor of Site and Situation Specific Art at the Finnish Academy of Fine Art. I love teaching and I thrive on the two-way feedback I have with art students. I take it as a great opportunity to develop further ideas of art as workshops and research.

BR: International curators travel around the world. Art travels. Can you give a little backstory to your recent project Poison and Play?

PL: In 2006 I discovered I was poisoned. It was a horrible experience, but it pushed me to pay attention to parts of my body that I had previously ignored. I was able to feel organs in my body that you're not supposed to feel, such as my kidneys, my liver, and I still feel my pancreas. My intestines were so irritated that they cramped when someone lit up a cigarette. I was really sick and couldn't eat anything sensual in food: no salt, oil, or sugar -- just white rice, boiled carrots or beets, and water, and sometimes not even that, for two years. I also smelled and sensed everything acutely, for example, someone frying an onion miles away.

This experience put my body and my mind into a hyper-sensitized condition, forcing me to make very clear choices in my life. Suddenly it wasn't so important to be a famous artist any more. It was more important to survive and be happy. I also learned that happiness is not hedonistic, but the very key to life. If you are unhappy and sick, you are not going to get better. Happiness sustains life, which is why we need to play, hence the title. It's for this reason that we bought the farm in Finland.

BR: You were also interested in color theory -- an interesting tie-in to an otherwise conceptual piece.

PL: My healer told me that exposing myself to the color green, either by seeing it or through my skin, for example, green light on my skin, would help my body to heal. I also heard about a study that was published in Germany about how people in the countryside are happier than people in the city, because they are exposed to the color green. This news was hilarious, because when I was sick I was drawn to the color green. I bought green sheets, green shirts, green cups and mugs, everything was green, green; I couldn't resist it. And this was well before I visited the healer.

I am interested in the effects that color has on the human mind and physique, and the colored hammock provided a perfect color chart. In researching for this project I looked at Paul Klee's fascinating color chart. Klee was a visionary who saw color as this hugely sculptural space, where the blue becomes a cone that curves -- very spacey and futuristic. The idea is that in the middle the cone is thick and dense and at the edges it gets thinner and narrower until you have three colored shapes, the yellow, the red, and the blue, chasing each other in this wild circle of motion. When you create the cross sections anywhere on that circle, you get a certain color. The other part of the three-dimensional model was the white and black with the gray in the middle. I was intrigued with the shape of these colors and thought, "What if this shape was a hammock, twisted, into a parabolic shape?" I wanted to make it physical with a model. But, if I were to exactly replicate the Klee model, then these hammocks would be suspended in the air in a way that you couldn't actually lie in them. There would have to be a centrifugal force to throw you into that horizontal movement. So I took that idea and developed it further.

BR: You yourself have become something of a healer with your most recent performance, Kalevala treatment. That seems to relate to a lot of what has interested you in the last decade.

PL: I passed my first exams given by the Finnish Folk Medicine Association, moving from a novice to an apprentice in Kalevala treatment. Kalevala is the Finnish epic. It's the unwritten story of Genesis conveyed through songs, orally transferred from generation to generation, as was the Greek, the Icelandic, and the Native American Genesis. This oral tradition of Kalevala had songs that were entire descriptions of human anatomy, of medicine and herbs used for certain diseases, how to farm, when to do what or how to find certain things in nature, and so on. These songs contained all the knowledge of that society. This is why this treatment is called Kalevala, because it is a tradition transferred by generations through practice. It's not one type of massage. The long translation of the name is: Finnish traditional limb correction according to Kalevala. If you have problems in your spine or knees they can be treated in a very soft way, manipulating the body to correct itself. Osteopathy is similar, but, in addition, Kalevala invigorates the metabolism and deals with the meridians and the neural system, so it works on multiple levels.

Last summer I decided to work with other people's bodies, but I didn't know what form it would take. I had a dream where I saw living people's bones through their flesh. I immediately knew this was what I had been looking for.