Bradley Rubenstein: Let's start with the most obvious questions first. Seattle is, from my point of view, way out there. I've known a couple of museum curators who moved there specifically because it was, to quote one of them, "not a suburb of New York." How relevant is that to you? You definitely have a thing going on there -- your work, your gallery, your whole approach to what an art world is -- that is different than here or even, say, London or whatnot. There is a fuck-you-this-is-what-we-do thing going on.

Robert Yoder: Yeah, we do what we have to do, but so would anyone with a brain and a back. There is always this haunting image of Seattle being the last vestige of the Wild West, but I think that is romanticizing something that may not exist. My favorite description is “We're a Town that Thinks It's a City.”We don't have hundreds of galleries and dozens of museums to feed our individual needs, so we find what we want, and if we can't find it, we make it. I'm sure that happens in other cities. I've never thought of Seattle as being any different than anywhere else I've lived -- at least not in a way that affects my work. As I've gotten older, my approach has become more of a fuck-you, but that is probably because at the end of the day, there is just not that much to lose, but so much to gain.

BR: Obviously your work reflects that kind of attitude! Let's go back a little bit. Tell me a little about your background.

RY: Well, I was born and raised in Virginia -- southern Virginia, practically North Carolina. I moved to Seattle for graduate school and stayed. School was always about craftsmanship. My BFA was in metalwork/jewelry, and the MFA was in fibers. Both allowed me to make sculpture in ways the sculpture departments weren't interested in. Those classes really instilled an appreciation for detail and the power of material. That was twenty-six years ago.

In the early '90s, I got really sick, had some surgery, and followed up with radiation treatments. That period was pretty awful, but I did gain a lot from it. It slowed me down, and I started paying attention to things. I had the sense I was just outside my body. That feeling is kinda with me at all times now -- just some endless disconnection.

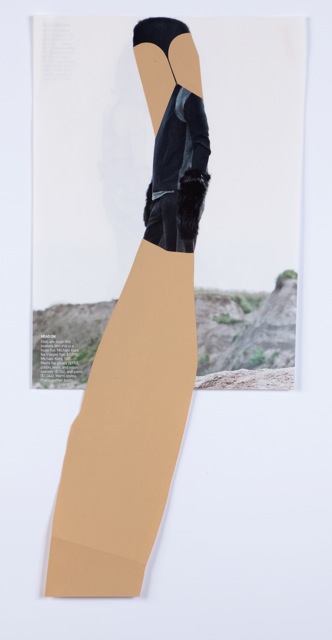

(right: "Dry Ship," 2010, collage, 12 x 9.5 inches)

(right: "Dry Ship," 2010, collage, 12 x 9.5 inches)

BR: That is relevant background material. That is exactly the way I would describe your work: being outside your body. You paint and collage things on paper. The paintings are related to bruises, skin, etc., and the very nature of collage is surgical. Do you see your work as being autobiographical?

RY: There is some weird notion of anonymity that I'm trying to maintain. I'm pretty withholding, and my disconnection lets it feel natural. (Call the shrink now.) I guess I don't purposefully think in terms of autobiography, although there have been a few veiled self-portraits along the way. For me they seem more like an extension that has a better grasp on nuance and blatancy. I think of the paintings as if they could yield under slow and steady pressure, sucking in your hand, then arm, then whatever else fits. The imagery forms, only to fall back. This back and forth area of being and not quite being is the address for my indifference. Seems too simple to say, "I pour my soul into them," or some other bullshit. When I'm painting I feel like I'm pulling things out more than pouring in.

Thinking in terms of skin and bruises, well, skin and bruises are just plain sexy, and all the paintings have an undercurrent of sex in them. The skin is the first contact, and the next thing you know, you're getting sucked in. The paintings are usually about specific people I know, but it is just barely them. Like when I paint my friend Carl, I know he has a scar, so I paint the scar. I can see it, so it becomes a portrait of Carl. Nobody else can see it, but should that matter? The collages are similar but rarely about anyone in particular. They tend to be more about covering things, hiding things. The surgical aspect in them is purely editing, it relates back to the tedious (read: anal) hand work from my craft education.

BR: You make the work seem connected in a way that I hadn't seen at first. I saw the paintings as being something that was added on to, and the collage work as something that things were taken away from, both getting to a point, but by different paths. It is interesting that the element of craft is so integral to both processes. We can come back to this in a minute, but I want to bring in another aspect of your work, which is the gallery. Do you see that as relating to your work, or is it something else entirely? You are very specific with your shows, and how you present the work is very precise. The context, the catalogs you do -- all that becomes important.

RY: The gallery was a long time coming; I had been thinking about it for maybe five or six years before it happened. I think the economic collapse was just the thing I needed to push me. There was a lot of support from friends, especially from my partner George, and from Charlie from Ambach & Rice (LA). I thought running a low-maintenance gallery would create some perfect diversion that hopefully a few like-minded types would enjoy. I'm humbled by the relative success in the short time it has been open, and that success has pushed me to work harder at the shows. I don't think it relates to my paintings except that I'm a happier person, and that probably spills into the studio somehow.

I couple the artists in each show because I see some tenuous connection between their work and then just let them do what they want. Sometimes I just want certain things the artists create, like just their drawings. I have to have slight control with the show because of the logistics of exhibiting in my living room, so sometimes the really big stuff just can't show. Mike Simi has a gigantic mechanical sock puppet that is made from those arms that build cars. It's goofy funny and would just crash through to my basement -- as if it would even fit through the front door.

Anyhow, the show design has to fit the work, or I should say, has to fit my idea of the work. One of the hard things for an artist is to give up control and let someone else hang the work. I resisted for a long time myself. I finally got it one day, and it was a revelation. When you let someone else hang it -- too high or too low or in the corner or whatever -- you get the opportunity to see your work new again, maybe even see what a stranger sees in it. It's not being evil or controlling, but I do think it is important to do this to artists, especially younger ones who are always dead-set on the proper way and order to hang their pictures.

The catalogs are important for the artists so that they have some written record of the show. A written essay by a learned person about your work isn't something you get everyday; these things are important. I think a lot of what I'm doing with the gallery is the fantasy stuff I always wished my galleries did. Keeping with my withholding tendencies, the gallery website is pretty minimal: no résumés, no endless thumbnails of every artwork, just an image, some text, a news page, and a contactpage. The Facebook page has more if you want it, and besides, everyone knows how to Google an artist.

BR: In a lot of ways all this ties together, I think, to your work. It shows a level of interest in how art is created and also presented -- very detail-oriented -- which I think is reflected in your paintings and collage works. It also seems like you must absorb a lot of information from working closely with all of the artists and writers with whom you end up working. Is this at all true?

RY: It is, and I do absorb a lot, but not only from the artist and writers. Lately I've noticed I'm paying attention to things I never really cared about. Once, when I was in Wyoming a few years ago, the sunrise on the mountains did this thing that was completely the opposite of everything I had learned about atmospheric perspective. It was unfuckingbelievable. Since then, I just let go and let whatever happens, happen. When an artist lets me see something in myself that I never knew had been there all along, well, THAT is the shit. That moment is great. That is when this whole new gate opens and so many things make sense.

(right: "Head On," 2010, collage, 17 x 8 inches)

(right: "Head On," 2010, collage, 17 x 8 inches)

BR: Do you see your work coming from any specific historical thread? Do you have any specific affinities or influences from past art that you can point to?

RY: Not with any clarity; I have favorite artists but they tend to make very different work than I do. When I was a kid I saw my first Duane Hanson, and I still remember how it creeped me out, but I couldn't stop looking at it. Possibly because it was a full-on naked dude, but probably because it was so unlike anything I had been raised to think of as Art. Later in 1982, the Good as Gold show at the Renwick Gallery in D.C. affirmed the fact that low or base materials can be equally as important and beautiful. I'm glad I got to see those shows at those times; something probably sank in from them.

BR: You have a show coming up next month in New York City.

RY: Yes, the show will be at Frosch&Portmann in the Lower East Side and will be up the month of November. Pulse in Miami will also feature new work. There will be several oils on panel and some collages. I'm most excited about some combinations that introduce relief -- basically painting on a shelf. It is a stretch to call it sculpture, but it is working in that direction.

BR: Can we get a little preview of what the new work is all about?

RY: Well, it seems I'm always thinking about loss and how that crushing melancholy just seeps into every action and thought. So these paintings are depressed; they have a gloomy libido that is ready for failure. The show title is Beautiful William, which I totally stole from a Handsome Family song about a guy who goes missing. I've been listening to a lot of shoegazer music lately, and all that downbeat has me thinking of the paintings as sadcore.

BR: Sounds ominous. But we can't say we weren't warned.