Andrew Heard 21st August 1958 - 9th January 1993

The artist Andrew Heard was a combination of contrasts, contradictions and charm. Although his large immensely detailed canvases referenced quintessentially English topics, it is a testament to their brilliance of construction that the viewer didn't need to know who his subjects were in order to be engaged by them. Usually British actors, comedians and neglected television personalities held centre stage. It helped, enhanced and enriched the viewing experience if you knew them, but as he was more successful in Europe, the references were secondary to the visual impact of the work. Heard had more recognition in Germany where his paintings sold well via the Friedman-Guinness Gallery in Frankfurt, he also exhibited at Turske & Turske in Zurich, where the essentially English comic Arthur Askey held little in the way of a visual translation abroad. His work was initially monochromatic and stark but developed into a cavalcade of color. Andrew Heard's pictures are layered, complex and deeply emotional, littered with references both subtle and profane. The term exquisite could be applied to many of his works. They remain a gift to the eyes.

Heard was born in Hertford on August 21st 1958. He initially graduated in 1979 from the University of London with a degree in Art History, the year in which he entered the Chelsea School of Art. Whilst working as a waiter at the legendary Blitz Club he encountered the artists Gilbert & George, presenting them with a bottle of wine as a token of his admiration, but scarpering with nerves before he'd taken the time to uncork it. This brief commotion instigated a friendship which lasted till his death; he even featured as a model in some of their work, "Shame" being one notable example.

By 1983 he was living in West Berlin and later shared a studio in Garden Walk with the poet and artist David Robilliard (1952-1988). Just round the corner from Old Street tube station, it was a remarkable space occupying two floors of an old warehouse, the ground being the work area and open plan, whilst the first was roughly divided with plaster board partitions into room-like spaces. Needless to say it is now a luxury apartment block whose redevelopment was advertised in the national press. No aspiring artist could now live in such cold yet spacious luxury. There was a huge walk-in safe in the far corner of the first floor, although he managed to drill a hole in the door Andrew never succeeded in cracking the lock. It was like living with a mystery, one that intrigued and frustrated him in equal measure. He and Robilliard organized parties and exhibitions there. They were a combination of extremes. Andrew's mediative and considered contemplations were at the other end of the spectrum to David's didactic and spontaneous paintings. An odd artistic pair they both achieved much beneath the lingering and encroaching shadows of mortality It was an organic and youthful time, and with hindsight a sadly brief flowering of artistic freedom. David Robilliard died on 3rd November 1988, the opening night of Andrew's Cork Street show, Gilbert & George in attendance by his hospital bed. Andrew's painting "That's All Folks" was dedicated to David, adding a subtle, sad poignancy to the Warner Brothers cartoon caption that it celebrated with sorrow. It was a return compliment to David's poem:

A LITTLE POEM FOR ANDREW HEARD

You don't often see a goat on a London bus and if you did there'd be a lot of fuss.

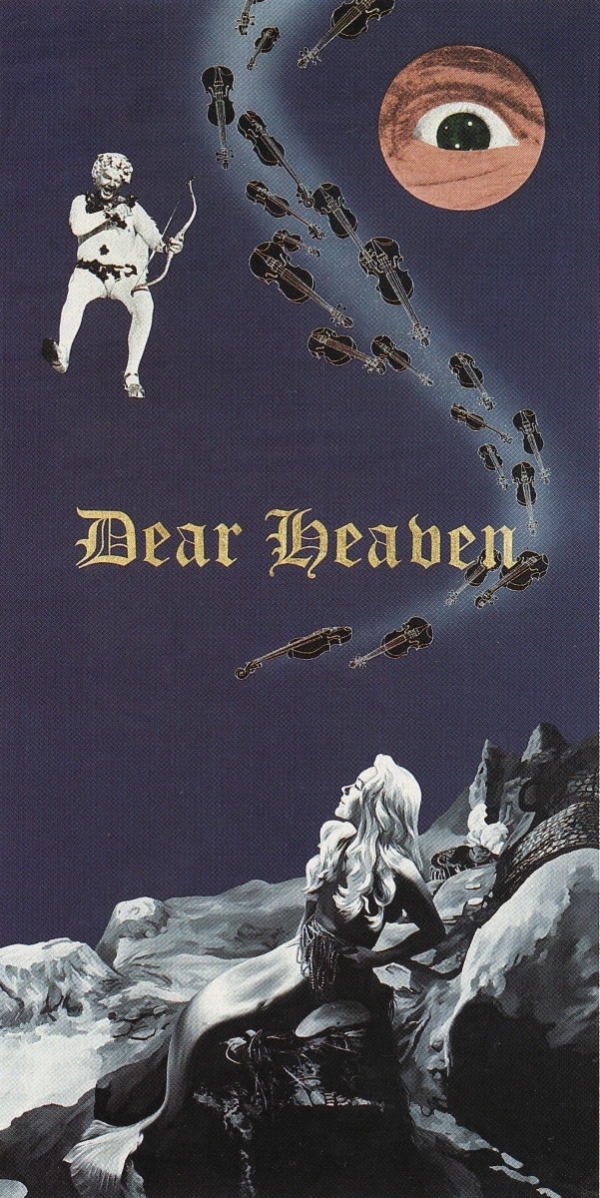

Most people wouldn't recognize the eye of Kenneth Williams as a leering moon in the picture "Dear Heaven" (image left) accompanied by Benny Hill dressed as a cherub taking aim at a mermaid from a largely forgotten black and white comedy of the 1950s. In this way, Andrew Heard harnessed and shared his interior world into a cohesive and evocative visual statement. His very personal obsessions would prick the curiosity of the viewer and inform them in the way that Morrissey's album sleeves still do. Andrew greatly admired The Smiths. He reflected in a 1990 interview with the art critic and poet Adrain Dannatt: "What I'm doing in art is in some ways paralleled by what Morrissey is doing with The Smiths. Their songs were based on observation, very human, very straightforward, and witty as well."

Morrissey was aware of Heard, but the two never met. Andrew however was quite aware of the eccentricity of inherent in his work and its methodology and myth making. He once wrote to me that he'd been up in bed reading a 1958 copy of TV Times which made him confess that he realized he really was a rather strange man. His letterhead was adorned by a bowler hat, a reference to his love of Terry Thomas, that utter embodiment of eccentric Englishness, and also a casual link to the skinhead mythology of A Clockwork Orange. Add to that Max Miller, Norman Wisdom, Margaret Rutherford, Joyce Grenfell, and host of major and minor English stars of the '50s and '60s, and there was an elegiac nature at play, re-inventing the past as a means of explaining the future.

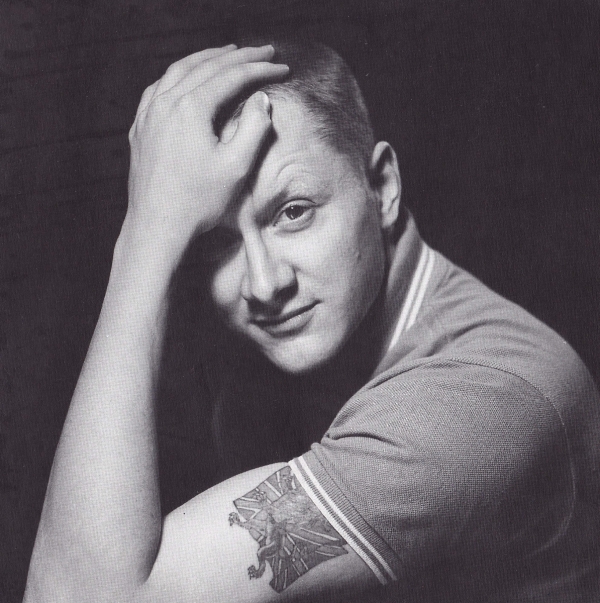

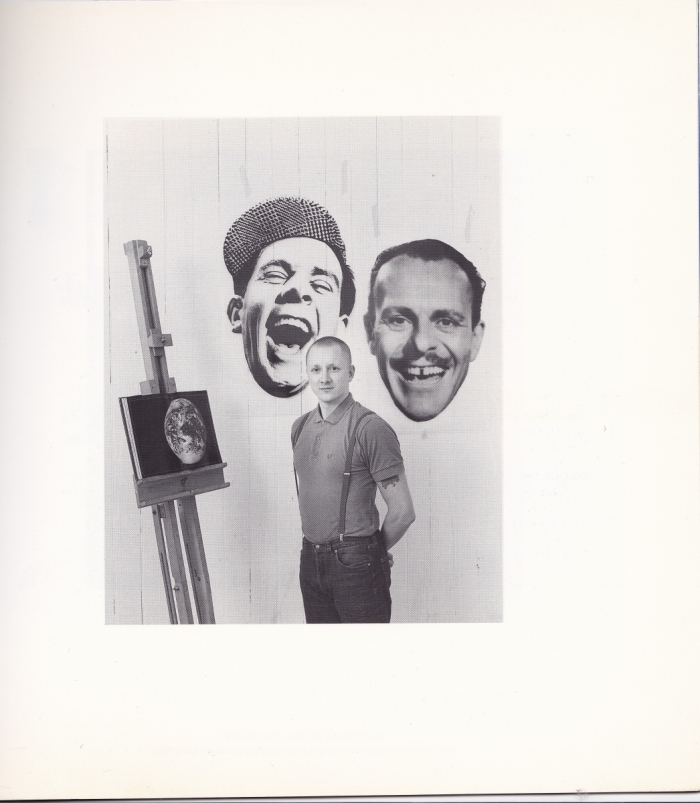

Andrew Heard wasn't merely a merchant of nostalgia. Via his great love and affection for images and colors that held echoes of his childhood he created an expansive and intoxicating world. There is great humor and pathos in his manifestations and he was continuing in the footsteps of the likes of Peter Blake, Pauline Doty, and early era David Hockney. He was essentially a pop artist, an English Warhol since his paintings also contained slogans from advertising campaigns of the yesteryear, and were often a mix of painterly technique and screen-printing, whilst referencing cinematic cliches. His art reveled in the status of the outsider, which he enhanced by his physical appearance as a skinhead. He had honed that look to perfection, the braces, the jeans, the shaved head, all in utter contrast to his impeccable manners, his soft-spoken nature and his chosen mode of transport, his pride and joy, a vintage TR7 sports car. Seeing him step out of it was a rather jarring, almost comic confection. Despite his meticulous nature, and having pulled off a very good line in downward mobility, tattoos and all, he had little time for the pretensions of the art world he had to inhabit. Once, in another letter, he was bemoaning his rather frustrating dealings with a lady who was determined to have her own way. He archly informed me that I had to remember that she was from the "Art World" where if something means nothing it therefore has to mean something! He was also a regular contributor to the letters page of the Evening Standard, usually on the decline of the British manufacturing industry in general, and of British cars, in particular. He managed to straddle this patriotic aspect of his nature with a profound sense of irony.

Nothing was too low brow to be included in his paintings. He referenced everyone from the Kray twins to such cult television classics as The Avengers, Ealing Comedies and the Carry On series of bawdy smut. He even sent flowers to the hospital where one of their major stars, the camp and effete Charles Hawtrey, whom he had included in the paintings, was dying, and adored Barbara Windsor, another Heard subject along with Sidney James. By delving into the past his work created subtle symphonies for the present day to dwell upon. One of his most evocative and haunting works -- "Happy Ever After" -- a tondo that features the boy from the Pears Soap advert looking skywards. Against a classic English country lane background whilst staring up at bubbles, each one containing a forgotten television personality, it is both wistful and melancholic. An achingly powerful image and one that deserves greater recognition. Although his career was in ascendency for much of the Eighties, by the time of his death in 1993 life had taken a dark and distressing turn. One of his galleries had gone into liquidation which resulted in the loss of many of his paintings and he was dealing with the infirmity brought on by his HIV status. Had he survived into the era of Blair and Blur he was the perfect visual advocate for "Cool Britannia." The round canvasses he created in his final years are a perfect cohesion of his vision and ability, and remain strikingly wistful and startlingly unique. For all their lingering tenderness, they possess inevitable intimations of mortality. At his memorial show amongst those in attendance on the opening night were David Hockney and Gilbert & George. His painting "Lovechild" (below) is a metaphor of gentle fragility; moths and flame and a fading innocence.

Andrew Heard tirelessly and successfully promoted the work of David Robilliard in the years after his friend's death. Nowadays Robilliard is rightfully recognized as an important and ground breaking talent, having recently had a major retrospective at the I.C.A in London, whilst Heard's reputation is almost entirely forgotten. There is talk of a show in London sometime soonish but apart from the occasional picture in a group exhibition, and a small exhibition in Germany last year, organized by the gallery owner Rob Tufnell, his work is a treasure trove that awaits rediscovery as a reward to those who have never encountered it, especially in his home country, where his references could easily be de-coded. Despite the use of nostalgic images there is nothing dated about his artistic output. It is witty, vibrant and enchanting, and very much like the man who created it. Given his montage and magpie outlook Heard would have been an inspired participant in the digital revolution, which would have suited him perfectly. A few years after his death a major gallery turned down a proposed exhibition of his work because the gallery felt it was too sad, a perfect case of getting the point whilst missing it completely.

Gilbert & George once wrote:

"Andrew's belief in himself as an artist of England resulted in a unique body of pictures that are as English as fish and chips. (A favorite supper of his.) Andrew was a public-school boy with lower-class aspirations, dressing as a skinhead, behaving as a gentleman."

One Sunday afternoon whilst we were returning from Brick Lane Market where many of the vendors would simply discard what they hadn't managed to sell, I picked up an old annual from the 1930s laden with sepia photographs. After a quick flick through the pages I put it back on the pavement. Andrew enquired why I didn't want it? I just shrugged absently saying I'd lots of things just like it and didn't need another, but maybe he should take it as there might be something there he could blow up on the photocopier and turn into a painting. I instantly realized how dismissive those words sounded, and began an apology, but he just smiled and said: "I think you rather know my working techniques a little too well!" As we approached Garden Walk he suddenly knelt by a small patch of earth exclaiming with genuine delight. "Oh Wow! They've come up!" He was gently stroking some crocuses in bloom. "I planted these!" he explained and then looked at his skinhead regalia and sighed knowingly, "I guess that wasn't terribly butch!"

He once related a comic tale very much at his own discreet expense. Having saved vouchers he'd managed to secure a weekend break for two at a hotel on the South Coast of England. In the middle of the night there was a fire alarm and the building had to be evacuated. Outside on the lawn the guests were assembled as an inventory was undertaken. When it came to Andrew's booking the manager called for "Mr. and Mrs. Andrew Heard." After a second or two of understandable hesitancy, Andrew stepped forward exclaiming "That's us!" The guests looked round to see him accompanied by Chris Hall, his partner, sometime model, and at over six foot tall an imposing if somewhat menacing figure who'd graced the cover of Italian Vogue. Their embarrassment was saved by an apparition appearing in the supposedly empty hotel's doorway. It was an elderly woman who'd finally made it out on her walking aid to utter the immortal query: "What's going on?" Had there been an actual fire she'd have been cremated.

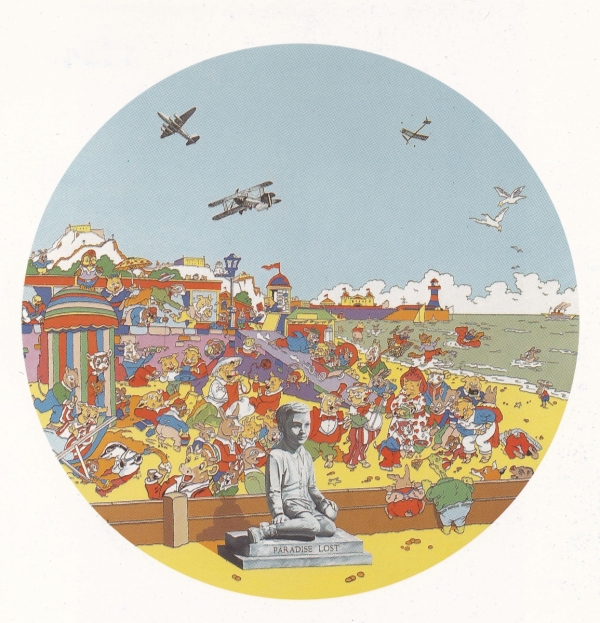

Twenty-five years on from his demise his intelligence, wit and artistic talent remains a tangible loss, both to those who knew him, and the wider world, but in order to be reassessed and valued afresh one needs to first of all be remembered. An artist of importance with a talent to amuse Andrew Heard remains a profoundly unusual individual. He was "Pop" but with a sense of history and tradition, nostalgic without falling foul of sententiousness, and a purveyor of an Englishness in decline without subscribing to exclusivity. There lies the essence of his creativity. It was, and remains a visual prayer to a fading past, and one that he deserves to emerge from in order to inform and remind us that we are all products of it. In the painting "Paradise Lost" (above) there is a cavalcade of cartoon fun on a beach, a wonderfully colorful pean to childhood vivacity and imagination, but eventually the viewer's eye is drawn from the comic book dynamic to a statue of a small boy with his hand resting upon a ball, as frozen and as static as the background is chaotic with delight. The painting is a parable. We cannot recapture the former happiness, the innocence of childhood, can only try to remember it as best we can for there is no point of return. That subtle directness encapsulates the work of Andrew Heard. Modernity with an almost Victorian morality at its core, and a profound feeling of elegy and a narrative of sorrow. Few artists possess such an intelligence and power.