Saints, Sinners, and the Collective Unconscious is riveting. Mr. Lombardi is an artist with an intimate understanding of history in regard to religion and popular culture. After careful viewing of the 30 works in the exhibition, I was compelled to research the titles of the works because they seemed to hold the key to unlocking Lombardi’s intentions. I focused on the works in the Saints section of the exhibition because I found their cryptic iconography most intriguing. The research of the saints depicted in Lombardi’s work opened up a new route for me to access the works’ meaning.

Saints Francis of Paola (2016-2017)

Lombardi started this piece (below) in 1964 when he was first getting into painting as a ten-year-old boy. He came back to it fifty years later. He first painted the oceanic backdrop and later added the white bearded seaward traveler dressed in the robes of a friar. A year later he added the pitchfork wielding demon that helped bring forth the final touches that resulted in this very beautifully biblical painting. I found this piece particularly intriguing as it immediately caught my eye. I lingered at this piece without a word, utterly taken back far longer than I would have anticipated. This was due largely in part to the aesthetically pleasing symmetry to the piece. A gust of wind can be traced from the lower left corner to the upper right corner of the frame. Everything from the ocean, to the sail, to the sailor’s beard is taken by this relentless wind.

Our sailor appears to be either sailing through rocks or trapped between them. These rocks can represent a deeper allegorical meaning. I see these rocks as mistakes and missteps along the path of uprightness and kindness. The rocks can represent the inner turmoil and history of the observer. They can represent any and all life complicating issues. The demon is always ready to pounce if the skiff crashes into the rocks. The demon is equally as ready to send the sailor along by sending a wave his way.

The title got my attention and it forced me to search into the meaning behind it. I was immediately brought to a wiki page that gave me a report of the life of one Saint Francis of Paola. He was a merchant friar but was never actually ordained as a priest. Saint Francis founded the Roman Catholic Order of Minims in the 16th century. A legend told of how he was refused passage on a ship that was to take him across the Strait of Messina to Sicily. Being that he still needed to cross, it is said that he laid his cloak on the water and tied one end to his staff as a sail. He then sailed across with his companions following in a boat. Perhaps that is what Lombardi is depicting being that no actual boat, or even skiff, is visible.

Saint Joseph of Cupertino (2016)

I was not quite sure what to make of this piece. I was first taken to think of the Space Race being that the backdrop is a splash of space exploration. The description of materials used points out that the backdrop was actually a vintage game board from the 1960s. A daring astronaut stands defiant and willing to embrace the dark void of outer space. Rockets are being launched into orbit past an already established satellite. The scene may have appeared science fiction to the audience of the time but looking through modernity the scene appears to have been rather a tactical use of propaganda because at the time the U.S. was competing with the U.S.S.R. to be the first to have a manned mission to the moon, being that the Russians where the first to send a satellite and a living being into space. This could have served as the piece; however, Lombardi has also included a seemingly Franciscan friar with a space helmet on his head. The friar appears to be floating and his arms are able to move in a circular rotation. I was first given the thought of Copernicus and his radical discoveries including how the earth existed in a heliocentric solar system. However, being that Copernicus was not a friar, I was then led to the thought that the Roman Catholic Church denounced the discoveries of Copernicus and would have called these theories blasphemous.

The title is where I found most the intrigue, however. A search led me to a Saint Joseph of Cupertino that lived from 1603-1663. Joseph of Cupertino believed that he could levitate when stricken with potent fits of ecstasy. This led him to be a victim of the Spanish Inquisition being that levitation was akin to witchcraft. He was moved to three different friaries for observation. Perhaps Lombardi is suggesting that Joseph of Cupertino entered into the wrong profession and his fits of levitation could have been more appreciated in an arena that dealt in cosmology.

Saint Kateri (2015)

Saint Kateri (2015)

Lombardi demonstrates an enthralling scene that represents an allegory of peace and the bridging of cultural divides. This is apparent in how a tree with the face of a woman seems to float over a river to connect the two sides of land. A bird hovers above the tree. There are barren trees on both sides of the river as if no life can be sustained there. The tree has the face of a woman, quite literally. This contradicts the infertile land with a depiction of a fertile woman. Lombardi goes even as far as depicting a humanoid head and hair in the form of leafless branches that grows down like a shock of hair. The head of the tree is on the left bank of the river and the roots are on the right. The tree has two distinct marks like the bark has been shaved off, as if the tree is scarred.

I was intrigued from the onset of observing this piece and my initial thoughts where of a link between nature and man. Perhaps the barren land is a representation of over industrialization and the death of natural ecosystems. As with the other pieces within the Saints exhibit, the title’s had the most impact on me. I again made a search and discovered that Saint Kateri was Indian woman of the Mohawk tribe and was born in 1656. She died at the age of twenty-four. During her youth her village was struck with smallpox. This killed a lot of members of her family and left her face scarred. Saint Kateri took a vow of celibacy and was baptized in the Catholic Church at nineteen years old. Pope Benedict XVI canonized her in 2012. The depiction of the tree is can be meant as an allegory for Saint Kateri. This is apparent in how Lombardi calls on the notion of the reverence that Indians had for nature and the reference to Kateri’s scars in the form of the shavings on the trunk of the tree.

She was widely denounced from her tribe for accepting Catholicism; perhaps this is why Lombardi has placed her roots on one side of the river and her head on the other. I’m led to believe that Saint Kateri provides a bridge over the waters of turmoil for Indian and American relations. Perhaps the backdrop is a desolate wasteland because it was the victim of years of strife and genocide. Perhaps Lombardi is suggesting that now, in a more civilized contemporary age; we may be better able to bridge the cultural divide to seek a more everlasting peace.

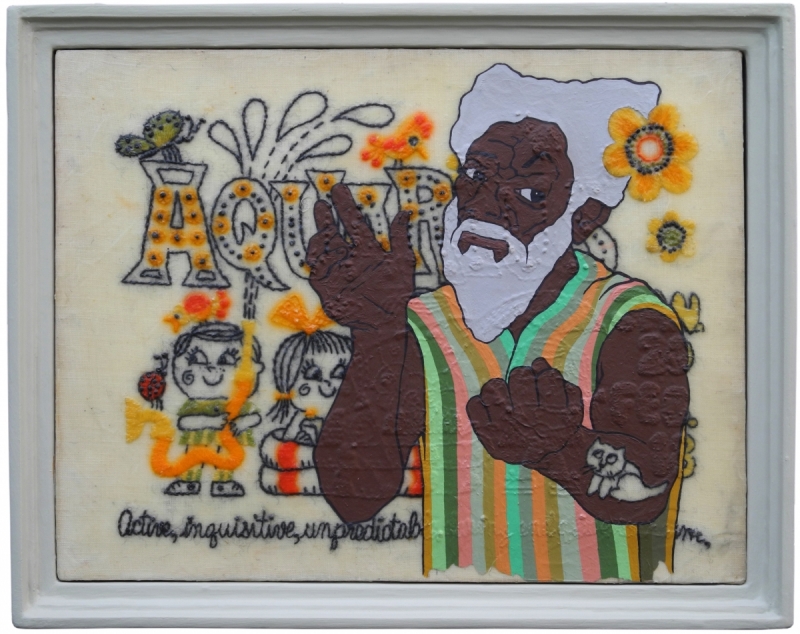

Saint Moses the Black (2015-2017)

I was initially unsure what to make of this piece. My eye was first drawn to the old, gray and bearded, black man. The old man is wearing a multicolored pin striped sleeveless shirt. His right hand is open to the observer and his left is clenched in a fist. There is a small cat that appears tattooed on his left forearm. I’m led to the thought of equality and openhandedness from his posture and attire. Perhaps his shirt could represent the rainbow flag of equality. The piece truly comes alive when consideration of the materials used arises. The backdrop is a salvaged needlepoint and the painting of the old man was captured with acrylic paint over the face of it. With consideration of that I’m led to believe that perhaps this could be a depiction of the potential needle-worker. The needlework itself is impressive. It holds a picture of two cartoonish children. There are flowers all around. (Image at top of page)

What I found most intriguing was the title. After a search I was led to believe that the old man is yet another depiction of the saint for whom the title is named. Saint Moses the Black was a physically imposing man born in the year 330 CE. He had been a servant of a government official in Egypt and had been discharged for theft and suspected murder. It would seem that Moses the Black was indeed a thief and after a string of robberies sought sanctuary with a sect of monks. He eventually repented for his sins and joined the monks’ devout society. Stories tell of his generosity, his strength of both pious practice and character.

I believe Lombardi intends this old man to be one such Saint Moses. I see a direct correlation in how Saint Moses’ hands have been arranged to how he is thought to have died. Differing accounts say that he died peacefully by the side of a fellow monk or that he was martyred when a group of robbers ransacked the monastery he called home; killing Saint Moses and a group of monks that stayed behind with him to allow the others to escape. Both accounts place his death in the year 405 CE at the age of seventy-five.

see a link in his hands to his death because it is unknown if Saint Moses died peacefully with an open hand or by the sword with a clenched fist. Perhaps even the jagged bumps that appear on the paint that portrays Moses skin can be a testament to the struggles of Saint Moses’ life. I can say without hesitation that I do not truly know why the well-painted portrait is on the needlework of the children. Perhaps it is because of the three words that appear in the lower left of the frame, “active, inquisitive, unpredictable…” the rest of the words are illegible. Perhaps these words sum up what it means to be a child, but maybe these characteristics belonged to Saint Moses the Black. A story tells of how he did not always play by the code of conduct but remained a pious monk through out. Perhaps Lombardi is suggesting that these characteristics are how life should be lived.

see a link in his hands to his death because it is unknown if Saint Moses died peacefully with an open hand or by the sword with a clenched fist. Perhaps even the jagged bumps that appear on the paint that portrays Moses skin can be a testament to the struggles of Saint Moses’ life. I can say without hesitation that I do not truly know why the well-painted portrait is on the needlework of the children. Perhaps it is because of the three words that appear in the lower left of the frame, “active, inquisitive, unpredictable…” the rest of the words are illegible. Perhaps these words sum up what it means to be a child, but maybe these characteristics belonged to Saint Moses the Black. A story tells of how he did not always play by the code of conduct but remained a pious monk through out. Perhaps Lombardi is suggesting that these characteristics are how life should be lived.

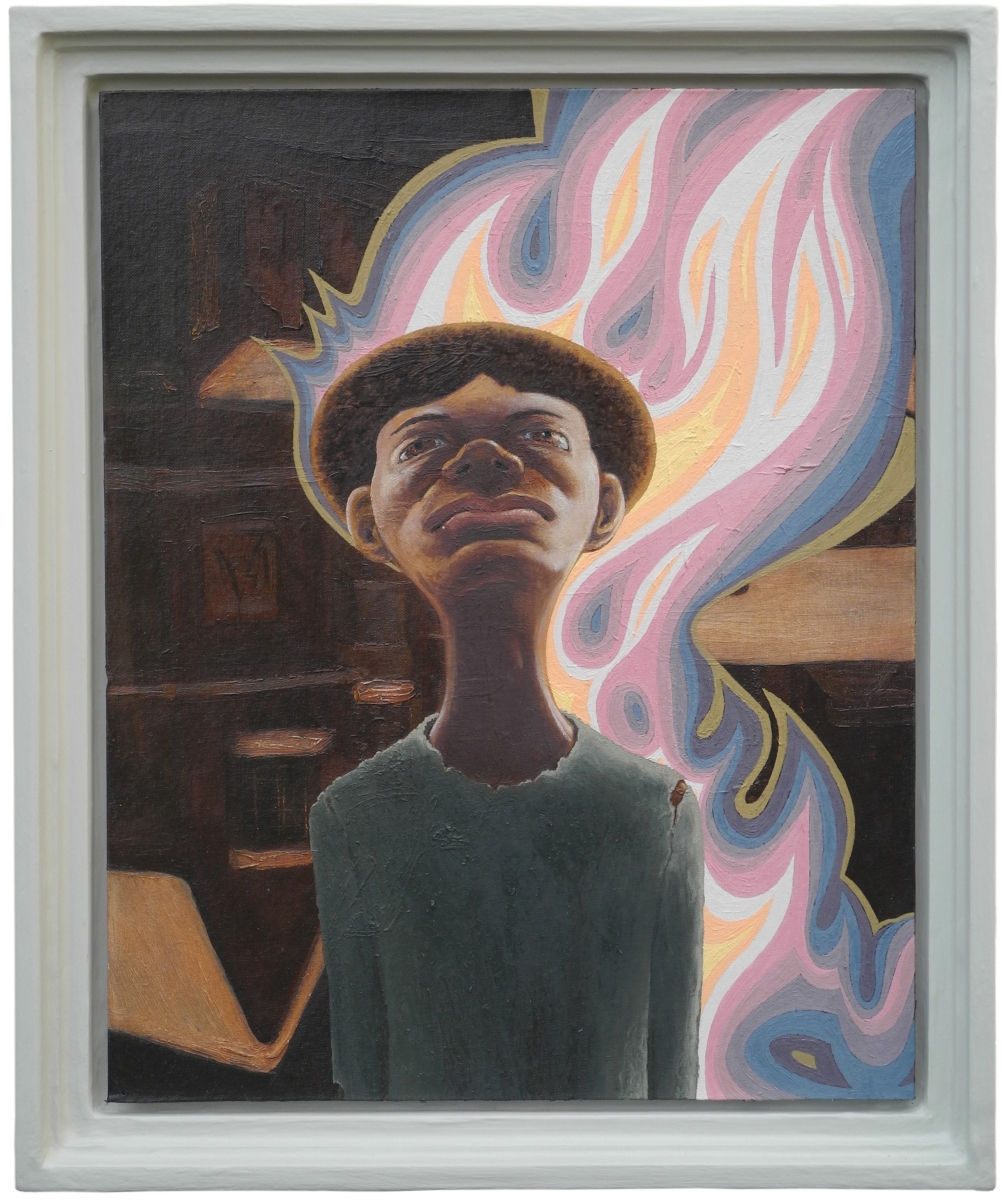

Saint Kizito (2016)

This piece has a flare of destruction, death, cleansing, and even rebirth. My initial thought was of something evil and I was puzzled by it being in the Saint exhibit and not the Sinners because surely arson is a sin. I went even as far as to feel a conjuring of the devil. I got this feeling because of the seemingly small black child standing in front of the roaring flames of what looks like a room, perhaps a library, on fire. I thought of demons and hellfire because of Christopher Marlowe's Doctor Faustus, in which Mephistopheles, an agent of the devil or perhaps the devil himself, first appears to Faust as a small black dog. The very same character interaction that inspired Led Zeppelin's "Black Dog." The seemingly small black child made me think of the small black dog because of the flames of the fire and my association of fire with the notion of demons dwelling in hellfire and brimstone. I thought it was interesting because Mephistopheles first feigned weakness by appearing as a dog, I thought perhaps it was being called upon again as someone also non-imposing: a child.

Lombardi has again incorporated recycled materials and, like Saint Francis of Paola, used previously painted pieces as the backdrop. I was given the sense of rebirth for this reason and that there is a depiction of fire, which has qualities of reincarnation, particularly in mythology featuring the immortal phoenix. Fire is thought to have cleansing properties in that it is a very powerful tool of destruction, thus I am puzzled as to why this piece is also a saintly theme.

Like the other works in the Saints exhibit, the title has greater meaning. A search revealed that Saint Kizito was a thirteen-year-old Ugandan martyr that was burnt alive in 1886, shorty after being baptized into Catholicism, by King Mwanga II of Buganda. Upon searching the context of the title, the fire makes sense. This is the most powerful and gripping piece in my humble opinion because of its depiction of courage in the face of certain death. Now having been provided with a historical framework I am left with a total reverse of thinking because I am currently feeling that the child was not the bringer of fire, he was the one burdened by it, destroyed by it. This piece was originally one of my favorites but now makes me sad when I call back to it. I feel a sense of almost shame that I was assuming evil in the child. Perhaps the old proverb is correct after all, you can't judge a book by its cover.