Very few have pored over a face as does Antoine Roquentin in Sartre's Nausea:

I lean all my weight on the porcelain ledge, I draw my face closer until it touches the mirror. The eyes, nose and mouth disappear: nothing human is left. Brown wrinkles show on each side of the feverish swelled lips, crevices, mole holes. A silky white down covers the great slopes of the cheeks, two hairs protrude from the nostrils: it is a geological embossed map. And, in spite of everything, this lunar world is familiar to me. I cannot say I recognize the details. But the whole thing gives me an impression of something seen before which stupefies me: I slip quietly off to sleep.

So what's in a face? What can one's physiognomy tell us? Or more to the point, what do our attitudes towards others' features reveal?

"If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face -- forever," Anais Nin instructed.

To be blunt, we seldom notice the visages of those around us with any concern. Can you recall the looks of your taxi driver, delivery boy, store clerk, or hotel maid? This becomes more problematic when we blur the faces of a whole ethnicity or an entire economic class. When members of a group lose their individuality, they can lose their rights -- and their lives. The Holocaust, anyone?

Supplying further credence to the point, in the more recent past, Ronald Reagan noted, "Welfare recipients are a faceless mass waiting for a handout." If they're faceless, why deal with them?

Delving more into the psychology of why many of us walk through life with blinders on, James Baldwin wrote: "In the face of one's victim one sees oneself."

All of which brings us to a tiny art exhibit, Holly Wilmeth's "Faceless Portraits," at the Art Print Photo Gallery in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico.

All of which brings us to a tiny art exhibit, Holly Wilmeth's "Faceless Portraits," at the Art Print Photo Gallery in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico.

The Guatemalan-born photographer, whose work has been published in National Geographic Adventure and Time, here focuses her lenses on the impoverished at work and play in Cuba, Mexico, and Morocco.

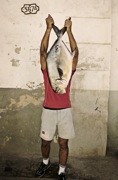

Each person pictured is both identified and obscured by his trade. A player of a double bass is hidden by his instrument. All you see are his legs and hands. The same with an accordionist.

In "Dye," the worker's red-tinged palms are held out to us blocking his face. Another's mask consists of huge tobacco leaves. In "Nurse," shot in Havana, a woman is clutching Latex gloves and syringes in their unopened wrappers where her eyes and lips would have otherwise been viewed.

Regarding each, it's hard not to project empathy upon these laborers. Especially with "Fish" (image, top left), in which a man, who at first looks like a young boy in dirty shorts -- his hairy legs are the giveaway -- is clasping what might be a huge flounder by its tail. Especially here, the anonymity seems painful. "Am I more than I wield?"

An added sense of poverty is detailed in each subject's chosen background: peeling walls, weeds, and dirt-encrusted doors. Yet there is a vibrant beauty in these photographs as well: the barrages of reds, whites, and aqua, plus the interplay of graffiti, make the eye happy while the heart laments.