A screenwriter bursts into his agent's office. "I have a great idea for a new picture," he enthuses. "We do a remake of The Wiz, only with white people." Clichéd Hollywood joke, sure, yet spot on, with regard to current received ideas of making art. The Reboot, Redux, the Remix -- pretty much any fucked-out form of production -- has replaced genuine individual expression. Part Matisse, part von Sacher-Masoch, part Mary Shelley, the work of Nicola Tyson draws from a wide range of inspiration while managing to pull off that most important feat in art, remaining uniquely her own.

Tyson is exhibiting her recent paintings and sculptures at Friedrich Petzel through November 5, 2011.

Tyson's drawings in the early '90s, were simple, small, black and white, mounted in groups. Abstract heads and bodies floated in little boxes, resembling a strip of film or a contact sheet. They had a cinematic quality that, at that time, resembled the work of Cindy Sherman. Like Sherman, Tyson created images that related in some ways to Leonardo da Vinci’s physiognomic caricature studies. Grotesques, but of a psychological sort, as if she were trying to describe what these characters felt like on the inside. Her early paintings elaborated on some of these ideas, with figures that combined an imaginary anatomy with references to bondage and mutant sex, like a cross between Salò and Alien: Resurrection. The critical response of the time compared her work to Francis Bacon, perhaps because of her stage-like settings, but this seemed off the mark. Where Bacon created literary, somewhat obscure theatrical tableaux, Tyson dove deeper into the psychology of her subjects.

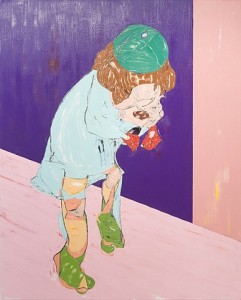

In the early twentieth century, Fritz Kahn created a series of books describing the physical body through visual metaphors drawn from industrial culture -- factory lines, combustion engines, refineries, etc., that sought to give a visual depiction of a new psychological understanding of the modern human being. Sigmund Freud, too, tried to describe new ways of comprehending the internalized being trapped in the body. Tyson combines elements of both in her recent paintings, working in a particularly British tradition of satire. In Figure with Sphinx (2011) she stages a tableau straight out of Oedipus. Figure with Pigeon (2011) has a gnome-like creature wrapped in swaths of cloth (resembling something out of Victoria’s Secret, but shredded) and the titular pigeon, resting on a hot-water bottle. It brings to mind other figure-with-animal compositions with weird twists, such as Titian’s Portrait of Charles V with Dog. In Figure Creeping (2011, above) Tyson refers back to the eighteenth-century caricaturist James Gillray, who described his work as "Mock Sublime Mad Taste" -- which pushes the satirical impulse toward something more anarchic, much like Malcolm McLaren and John Lydon would with the antics of the Sex Pistols 200 years later.

In a second gallery Tyson presents a series of small sculptures on plinths. The traditional presentation contrasts with the contingent feel of the pieces themselves. Fabricated out of self-hardening modeling compound, the diminutive works bear the fingerprints and marks of their creation. Highly abstracted, though not abstract, the little creatures resemble white swans, preening, laying eggs, and sleeping. One swan has been cast in bronze and patinated black -- making the whole of the group resemble some small puppet-show staging of Swan Lake. They project an eerie psychological element, with their immediate handmade facture -- they sway between being Degas-like studies and the work of mental patients. Hauntingly and ephemerally beautiful, they bring to three dimensions what the paintings can only show one facet at a time.

We ultimately come to identify with Tyson's project. We believe in the sincerity and depth of her probing; she penetrates the fine line between what can be seen (the exteriority of the subject) and what can be shown (its interiority). The promise of her earlier work is being fulfilled; we are now given the story, as well as the actors. As her homunculi lurch and creep across the canvas, we are drawn into their heads, and by proxy into Tyson. That ends this strange, eventful history, second childhood and mere oblivion.