Jerry Tartaglia: Is What Was

A few weeks ago, Anthology Film Archives did what it has done so well for decades. The venerable East Village institution spotlighted a director, Jerry Tartaglia, who has spent his life creating nonmainstream films that explore queerness, pornography, Nazis, AIDS, evil, love, homophobia, religion, the relevance of gossip, self-identity, and sexuality. But that apparently isn't enough karmic territory for Mr. Tartaglia. With each celluloid (or video) frame he seems to ask, "What is the essence of cinema? And what is filmic truth?"

In Is What Was (2008, 23 minutes, video), while exploring the exhibits at the Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp, a locale just north of Berlin where many gay men were tortured and slaughtered, the director notes, "In truth, Cinema cannot create the past. Cinema can only reveal what exists in the present."

But what is "the present"? When the film was shot, edited and first screened? Or is it "the present" of the viewer perceiving the work? For example, can Alain Resnais's Night and Fog, the classic 1955 Holocaust documentary, be viewed in the same manner today as it was when it was first released?

Yes, Mr. Tartaglia is mentally challenging, but never less than relentlessly entertaining.

Is What Was opens with a young man photographing a prisoner's uniform encased in a plastic box. There's a close-up of the sewn-on Pink Triangle and the unknown victim's assigned number, 45874. Then a flashback to 1933 as "Das Lila Lied" (The Lavender Song), a gay anthem of sorts, plays:

We are just different from the othersThose who love in boredomWith their uptight moral codesThey could experience a thousand wondersBut they choose banality. . . .We're children of another world.

Suddenly the film stops. Tartaglia is not satisfied. He has decided to redo his film. With white letters flashed upon a black background, he explains:

"This opening is not viable for several reasons. It is a failed attempt to recreate an imagined situation rather than portraying reality. The initial design of this film involved the documentation of sound and image to examine the formulations of Queer Identity, rather to create the imaginary. The Holocaust and the anti-gay hatred and persecution of the Nazis is not imaginary. It is what was. That hate is still alive today in America, albeit in a state of remission."

The film then begins again with a tour of Sachsenhausen from its exterior to its interior. We view drawings of the Nazis persecuting homosexuals, hanging gay men from poles by their wrists that have been tied behind their backs. Then we see the actual wooden poles with their long spikes that held the torturous ropes in place. There are three posts in a row situated in an otherwise long, empty courtyard. The only sound: church bells ringing.

A flash to the director in his editing room: "I want to make a film that doesn't rely on words." Then his camera swirls about a room at Sachsenhausen, which might be where deceased homosexuals were either examined or live ones were experimented upon or castrated.

A cut to Tartaglia pointing out that "queer history is uncovered through gossip and an unmediated image." For centuries, in fact, homosexuals and their contributions, let alone their existence and persecution, were expunged from mass consciousness by both historians and the Church.

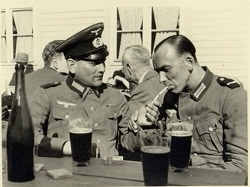

What follows are a dozen more snapshots of joyful Nazi soldiers at play. A homoerotic tinge seems apparent in the camaraderie viewed. Projection or reality? How can unrepentant killers appear so gleeful, and innocent, and at ease? "A positive, pleasant, and polite exterior can mask the most horrific internal reality," the text on the screen spells out.

From here on, Tartaglia comments on the cultural amnesia that plagues our generation, on the bravery of such early gay activists as Karl Ulrichs and Magnus Hirschfeld, and how there's a similar foundation for both the Nazi persecutions of gay men and the current American homophobia. Then he defines "evil." And there's more.

Is What Was is a short, brilliant documentary that illuminates while spurring on thought along pathways that you might not have ever previously considered pursuing. Happily, Mr. Tartaglia's genius is reflected in numerous other films and videos that are equally as accomplished, and thanks to the Anthology Film Archives and its support of his artistry, his work will consistently find new audiences.