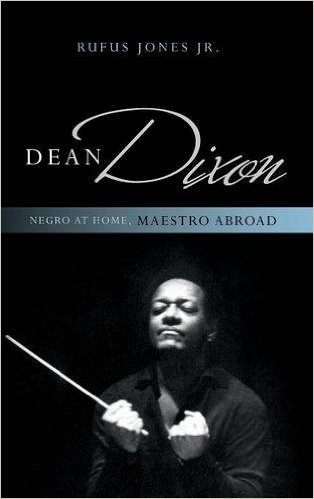

This is, I'm pretty sure, the first book-length biography of conductor Dean Dixon (1915-1976), the first African American to conduct the New York Philharmonic, and his story is so interesting yet largely unknown that it makes for a fascinating read.

Born and raised in New York City by immigrant parents (from Jamaica and Barbados), he started playing violin when he was three, at his mother's instigation, studying technique with a Russian teacher; by nine, he was playing on WNEW. He was also encountering racism; one prospective teacher cut off his lessons after Dean's second appearance, apparently because the building's residents didn't want a black child there.

Dixon was a good enough (if sometimes reluctant, it seems) student that he was consistently accepted into progressive, integrated schools. Once he determined to make music his career (after his mother was persuaded not to push him into studying to be a doctor), he passed an audition with Frank Damrosch to enter the Institute of Musical Arts.

Dixon's mother did, however, insist that he study to be a music teacher, as that seemed to offer the promise of steady work. It resulted in double the workload, but also set him on a path to form his own Harlem-based orchestra. He also got into the graduate programs at Teacher's College and Juilliard -- and attended both, simultaneously.

In the wake of the 1939 Marian Anderson/Daughters of the American Revolution contretemps, Eleanor Roosevelt lent a promotional hand to Dixon as well, which allowed him to lead his orchestra outside of Harlem for the first time in 1941 -- a concert which was attended, partly because of Mrs. Roosevelt's presence, by NBC's Music Director and the head of RCA, resulting in Dixon being hired to conduct the NBC Summer Symphony in two nationally broadcast concerts. His success at these concerts led to a regular-season engagement leading the NBC Symphony and a summer concert slot conducting the New York Philharmonic. And he was still in graduate school.

You would think this describes the start of a highly successful career arc, but that's not how it turned out. He got more guest appearances (one with the Philadelphia Orchestra soon followed), but no permanent conducting jobs, and he was unable to continue to financially support his Harlem group. Dixon then founded the American Youth Orchestra. Between that, his music-appreciation classes both in the city and on radio, and the lack of permanent conducting positions, he found himself typecast as more of an educator (the "baby specialist," as he put it derisively).

By this point, Dixon was married with a family to support. Lacking an American conducting post, he took an offer to go to France for two concerts with the French National Radio Orchestra near the end of 1949. Europe wasn't working out much better for Dixon until December 1951, when he stood in for the ailing Igor Markevitch at a Helsinki Orchestra concert radio broadcast, conducting Sibelius's Fifth Symphony (among other works). The composer heard the broadcast and praised the performance, and Dixon was invited to meet him, which he did. In Helsinki, Dixon also met the woman who would become his second wife.

Not only did the number of guest spots Dixon was offered shoot way up after he'd received the Sibelius seal of approval, he got a recording deal as well, and in 1953 he finally was hired as a principal conductor, of the Gothenberg Symphony Orchestra in Sweden. He remained a resident of Europe for the rest of his life, better received there (and in Australia, where he also got a conducting post) than in the U.S.

Heroes are supposed to be simple, not complex or flawed, especially not in the age of gossip columnists, but as the ancient Greeks had already noticed millennia earlier, heroes do have flaws, and Dixon was not perfect. He had three wives, his time with them (which is not to say the marriages) overlapped, and he did not treat his first wife well post-divorce. Jones does not ignore these facts, but he does downplay them to a certain extent, preferring throughout to keep the book's focus on Dixon's career. He thus notes that Dixon's lack of appearances in the U.S. after his move to Europe were, at least for a while, partly because he turned down invitations, ostensibly because they didn't fit his schedule, but really because he could be in legal trouble if he returned to the U.S. while being sued by his first wife for being delinquent in his alimony and child support payments. At first his delinquency is excused by pointing out his still-precarious financial state, but this non-payment issue persisted into a period during which Dixon owned two homes in Europe. Kudos to Jones for including some discussion of Dixon's legal difficulties with this issue and acknowledging the connection, but we do not get any explanations or documentation of Dixon's emotions regarding his marriages and the endings of two of them. When the legal situation was resolved --not by Dixon paying off the debt, but by a friend of his doing so for him -- suddenly Dixon's schedule did allow him to accept relatively short-notice guest conducting invitations in the States, including a triumphant return to New York in 1970 at the helm of the Philharmonic for a summer concert.

I could criticize Jones's talents as a writer -- the book's tone is sometimes a bit gee-whiz -- but first, he's a conductor who wrote this book because he saw the need for this biography and nobody else was doing it, and second, I'm guessing he deliberately kept it at a reading level that young readers could be comfortable with, and that non-musicians could understand, in order to get this story out to the masses. Despite Dixon's regrettable issues with his first wife, his life is an inspirational story of a man overcoming the linked adversities of poverty and racism to rise to heights in his profession that no black man before him had reached in the United States, and within that framework, Jones tells the story well, and certainly more thoroughly than anybody before him, which is why this book is both needed and recommended.