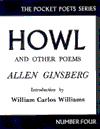

Allen Ginsberg's "Howl," published in Howl and Other Poems in November 1956 (the fourth item in the famous City Lights Pocket Poets series), is the most influential and iconic poem of the past half-century.

It went into the world with a wonderful introduction penned by fellow New Jerseyite and poet William Carlos Williams, who did as good a job as an establishment poet could of preparing an unsuspecting world for the force that was about to realign it: "Literally he has, from all the evidence, been through hell. On the way he met a man named Carl Solomon with whom he shared among the teeth and excrement of this life something that cannot be described but in the words he has used to describe it." And, "He avoids nothing but experiences it to the hilt. He contains it."

The poem is dedicated to Carl Solomon, whom Ginsberg met in a New York mental institution and with whom he had a relationship. (Some sources say they met when Ginsberg was institutionalized after an arrest, in lieu of jail; others that it was while Ginsberg was visiting his mother, Naomi Ginsberg -- for whom he would write the brilliant and heartbreaking "Kaddish" -- while she was confined.) All of the poem operates, on one level, as an indictment of Solomon's institutionalization; on another, that institutionalization and the reasons for it are an indictment of U.S. society.

Ginsberg in the first section compiles an epic list of non-conformists and their acts; the implication is that Solomon is considered mentally disturbed merely for being different, for not fitting in. This section also reads like a list of casualties, though some would say of their own overindulgences rather than of society; the wisest reading could perhaps be that society first provoked the overindulgences and then aggravated their results. The much shorter second section, written stoned on peyote, is an indictment of the ultimate source of our insistence on conformity: the worship of money (Moloch) and the resulting waste and destruction of all else: "Moloch whose mind is pure machinery! Moloch whose blood is running money!" The third section, also relatively brief in comparison to the first, returns single-mindedly to Solomon's predicament with repeated declarations of solidarity ("I'm with you in Rockland"). "Footnote to Howl" then caps it all with a statement of the holiness of all, from "The tongue and cock and hand and asshole" to "the groaning saxophone"; the bop apocalypse" to "forgiveness! mercy! charity! faith!"

That Eisenhower's smugly complacent U.S.A. was shocked and outraged is no surprise. That Fifties Father Knows Best world (already suspicious of Ginsberg merely for being Jewish) certainly didn't expect words such as "cocksucker" in its poetry, or proudly open homosexuality, or lawlessness or drug use or especially rampant rejection of capitalism. A verse such as "who copulated ecstatic and insatiate with a bottle of beer a sweetheart a package of cigarettes a candle and fell off the bed, and continued along the floor and down the hall and ended fainting on the wall with a vision of ultimate cunt and come eluding the last gyzym of consciousness" certainly wouldn't even strike most readers of the time as poetry (though The New York Times praised it).

Inevitably, there were repercussions. In March 1957, the second printing was shipped from England; U.S. Customs seized part of it. After that, City Lights had it printed in the U.S. to take it out of Customs' jurisdiction. When Customs didn't take the case to court, San Francisco authorities injected themselves into the situation. City Lights owner Lawrence Ferlinghetti and bookstore manager Shigeyoshi Murao were arrested on obscenity charges, with the line "who let themselves be fucked in the ass by saintly motorcyclists, and screamed with joy" cited.

Judge Clayton Horn rejected the prosecution's case, writing, "I do not believe that Howl is without even 'the slightest redeeming social importance. The first part of Howl presents a picture of a nightmare world; the second part is an indictment of those elements in modern society destructive of the best qualities of human nature; such elements are predominantly identified as materialism, conformity, and mechanization leading toward war. The third part presents a picture of an individual who is a specific representation of what the author conceives as a general condition. . . . "Footnote to Howl" seems to be a declamation that everything in the world is holy, including parts of the body by name. It ends in a plea for holy living. . . ."

The guidelines Horn laid down became precedent that allowed other material to be published in the U.S. In a way, Ginsberg -- and Jack Kerouac, Gregory Corso, William Burroughs, and others who came to be know as "The Beats" -- presaged the Sixties' counterculture and its freewheeling pursuit of perception-expansion, though in some hands that devolved into mere hedonism. Similarly, in the hands of lesser poets, Ginsberg's long-lined discourse on taboo topics disintegrated into formlessness and cheap shock value. But Ginsberg was tying together a number of schools of poetry -- Blake's ecstatic metaphysicality, Williams's colloquial rhythm, Whitman's long singing lines -- and dealing with serious topics in a nuanced way. The audacity of the construction of the poem's first section is that it is a single sentence of 2,146 words -- and yet it is laid out in such a way that it has absolute clarity even when Ginsberg is using words as they hadn't been used before ("unshaven rooms," for instance).

That many have imitated the cadences and use of language in the famous opening of "Howl" --

-- does not lessen the great value of the original. That the concerns of the poem remain relevant shows both the universality of Ginsberg's spectacularly personal vision and the rut our society has, if anything, dug itself deeper into over the past five decades.