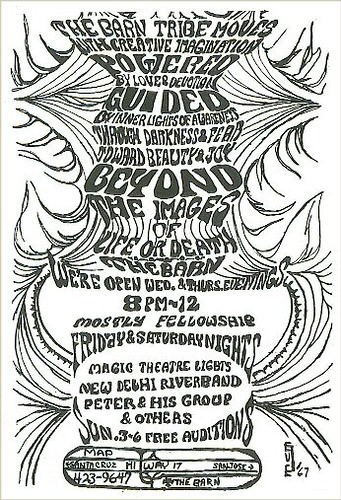

A few weeks ago, I went to the Other World show, sponsored by CultureCatch.com and DLO, at Great American Music Hall in San Francisco. The show featured my friend Gary Lucas improvising with computer/video performance artist Luke DuBois. I'm old enough to remember the "light shows" of the late 1960s/'70s, having lived in the hotbed of psychedelic visual/psychotropic/musical experimentation of that period. In fact, The Barn, promoted by psychologist Leon Tabory, (Neal Cassady's friend and psychologist) in nearby Scotts Valley (at that time a rather strange little place whose main attractions included an exhibit of strangely twisted "prehistoric" trees, several giant "dinosaurs" that could be seen from the highway, and an overly cheerful little "Santa's Village") was our town's very own cauldron of social/tribal experimentation via LSD and other substances, and a destination for such shamans of the eye and ear as The Grateful Dead, Country Joe and the Fish, Janice Joplin, Led Zeppelin (it is rumored), and Captain Beefheart (1965).

In my own writing, I turn obsessively to issues of time -- our immersion in it, and the seeming impossibility of grasping it. Attending this collaboration between Lucas and DuBois ended up being for me a meditation on past and present mind-bending experiences and temporality.

Light shows of the 1960s/'70s used overhead projectors, stage lighting gels, and various liquids and oils poured into glass containers set on the projectors, which were then rocked by hand and manipulated to go with the music. DuBois, however, uses state-of-the-art computer technology and software to create his "real-time phonography" performances. Differences between the two modes are obvious, but what struck me was the ability of the video artist and guitarist to evoke shifts in my experience of time. Both artists are composers, and I was curious to see how Lucas' music would play off of the visuals, and vice versa.

Lucas' guitar playing, hooked up directly to the computer, itself produced the imagery, with (apparently) some changes added by DuBois; the effects were immediate and spontaneous. Keep in mind that Lucas has played for Leonard Bernstein (debuting on electric guitar in Bernstein's "Mass" in Vienna), Rod Serling (that's right, Mr. Twilight Zone), and Captain Beefheart. One of my favorite pieces is his adaptation of Bernard Herrman's juggernaut soundtrack for Psycho. Unlike many musicians who utilize the psychedelic effect, Lucas does not necessarily "expand" one's mind in gentle ambient swirls, although he's quite capable of that; even playing solo, he is just as likely to shake things up, and he has the skill to do so in unexpected ways. When I walked in, he was playing a series of jagged, crunchy riffs that were peeling out angular shards all over the large screen behind him (his music has been described by some as tactile, almost chewy).

He has claimed at least one of his influences is literary: the Vorticists -- not so much Pound, but Percy Wyndham Lewis, of Blast fame, whose modernist journal was a product of the disorienting shocks of World War I, among other things. Lewis has written, "The New Vortex plunges to the heart of the Present; we produce a New Living Abstraction. Vorticist painting combines Cubist fragmentation of reality with hard-edged imagery derived from the machine and the urban environment, to create a highly effective expression of the Vorticists sense of the dynamism of the modern world." Lucas' guitar playing is astounding in his ability to produce driving, machine-like rhythms, drones, and hums--industrial aural landscapes--that melt momentarily into darkly disturbing, or sublime surreality: the heavy metal of the '70s recalling its literary roots in Mary Shelley's "Frankenstein" and Henry Adams's "The Dynamo and the Virgin." His re-working of Kraftwerk's classic "Autobahn" is an example, morphing into "Flight of the Valkyries." Wyndham Lewis would be pleased. Lucas' intent, however, goes beyond mere shock. While he has claimed that "vorticism...was based on the still center...intelligently observing the chaotic flux all around you," he also wants "...To prick the innards of another nervous system and hopefully hotwire that system to feel total ecstasy or pain or wonderment. To give people an orgasm. To make rich and strange paintings in sound." I much prefer this painful/beautiful reach into strangeness, rather than the current crop of hyperrealism in the media and films that attempt to make the "strange" as mind-numbingly "real" as today's latest war-mongering polemic.

By the time Lucas began fingering the lush bluesy chords of "Bra Joe from Kilimanjaro", the screen had turned black and white, taking on the shadowy graininess of silent movies. Luke DuBois performed his own considerable magic, as time-lapsed images of the guitarist appeared like ghosts of old rock posters or film clips, gently solarized. My recall of the order in which these songs emerged is admittedly faulty, as I began to wander in the aural dreamscape. Somewhere in there, I remember the chords of "Grace," the beautiful music Lucas wrote for the late Jeff Buckley, once a member of Lucas' band Gods and Monsters.

Soon the image of the guitarist, behind the actual guitarist, deconstructed itself into multiples, creating a meta-perspective of Gary that was reminiscent of Andy Warhol's portraits, but conveying a broader sense of the artist existing in multiple time-frames, some moving slower than others (or at least that's the effect it had upon me), some sped up -- lending an bizarrely nostalgic sense of time escaping one's grasp. It echoed Lucas's own work with old modernist films, live performances of the soundtrack he composed for the classic silent horror film, The Golem, (based on Gustav Meyrink's gothic novel) as well as soundtracks for Rene Clair's En'tracte (1924) and Fernand Leger's Ballet Mecanique (1924).

A curious difference between the liquidity of the old light show and the new technology is the computer's ability to mimic the drawn line, so that many of the images take on a graphic, hand-written quality; imagine drawn lines moving across a page, speeded up in time-lapse. One of the recurring motifs that I experienced (and I suspect it was purely subjective) was that of a written gesture recalled from time, momentarily fixed, then multiplied hundred-fold, whether it was a line scumbled across the screen, or the familiar gesture of the guitarist drawing his hand down over the strings -- becoming many, part of the larger human act of creating and communicating.

With the looping, rippling notes of "Strong Seed" (from Lucas's CD Skeleton at the Feast), the music became more recognizably "psychedelic." Accordingly, the angularity of images began to scatter like raindrops, taking on a distinctively "liquid" appearance, glimmers of light flaring on a cosmic river, or circling around a whirlpool--seemingly coming full circle in my mind--touching upon those first liquid moments on the overhead projector's screen in The Barn, in Winterland, The Fillmore, or the Avalon Ballroom. Time folding back into itself. Similar, yet undeniably different.