Prince didn't give a fuck what anybody thought about him.

You could say that's just what he wanted us to think, but his actions back up my assessment. Over and over he made choices that went against conventional wisdom. In the process, he built a counterintuitive career that made him a superstar, loved by the masses but also respected by such unimpeachable icons as Miles Davis (who compared Prince to Duke Ellington).

Saxophonist, composer, and musicologist Allen Lowe wrote yesterday, "As we pay tribute to Prince and others like him who have died recently, it's just a little too easy to repeat the clichés that describe them as expressing our generation, our history, our current world. In truth, as Richard Gilman said many years ago, what makes an artist great is not so much that he or she is of their time or a part of history but rather that what they give us is an alternative to that history. I do get worn down with the clichés of social significance; what made Prince great was really, as Gilman also said, that he was able to tell us the next things that we would be seeing hearing and thinking, even before we knew what they were. In this way he was very much like Bird, or Beckett; or Picasso, Haggard, or Ayler: A predictor of the future, or least of one particular kind of a future, in which radical changes in means and modes of expression were really confirmation of our own changing and ever-expanding consciousness."

If you're worried about what people think about your music (or any art) -- if you choose to do what's expected and safe -- you won't come up with something those people haven't heard before but discover they wanted to hear without knowing it until they hear it. Prince understood that. There's a scene in the middle of his movie Purple Rain where the club owner tells Prince's (semi-autobiographical) character, The Kid, "Your music makes sense to no one but yourself." And in truth, a lot of Prince's music seemed unusual, even weird, in the context of early '80s pop music norms. Consider that when he opened for the Rolling Stones at the L.A. Coliseum in 1981, he got booed off the stage after three songs, with some audience members throwing food at him and shouting homophobic slurs.

As the latter point suggests, Prince was flouting more than musical norms. Prince was the first African-American pop artist to flaunt an androgynous image in front of predominantly straight audiences. He dressed outrageously, whether in just bikini briefs or in ruffled shirts with purple suits or in a tight-fitting toreador suit. In an era when most male-fronted bands, especially R&B bands, didn't have female members except as backing vocalists or dancers, Prince's band The Revolution was integrated in race, gender, and orientation -- both guitarist Wendy Melvoin and keyboardist Lisa Coleman are lesbians, and though this was not openly proclaimed until later, the intro to "Computer Blue" flirted with a lesbian scenario.

Despite all the opposition he encountered, Prince believed strongly in his musical instincts. Even at the beginning of his career, he held out for a deal that would give him complete creative control and allow him to self-produce; only Warner Brothers' Lenny Waronker was willing to grant that freedom. When in Prince's eyes Warner Bros. reneged on their deal by refusing to let him release albums as often as he wanted to, he protested his treatment and left the lucrative safety of the major label in favor of life as an indie artist. Writing "slave" on his face and changing his name to an unpronounceable symbol brought ridicule. But since Prince didn't give a fuck what anybody thought about him, he stood his ground. The result is not just a legacy of superb albums that lives on after him, beloved by millions, but the more tolerant and diversity-friendly culture in which we live nowadays. - Steve Holtje

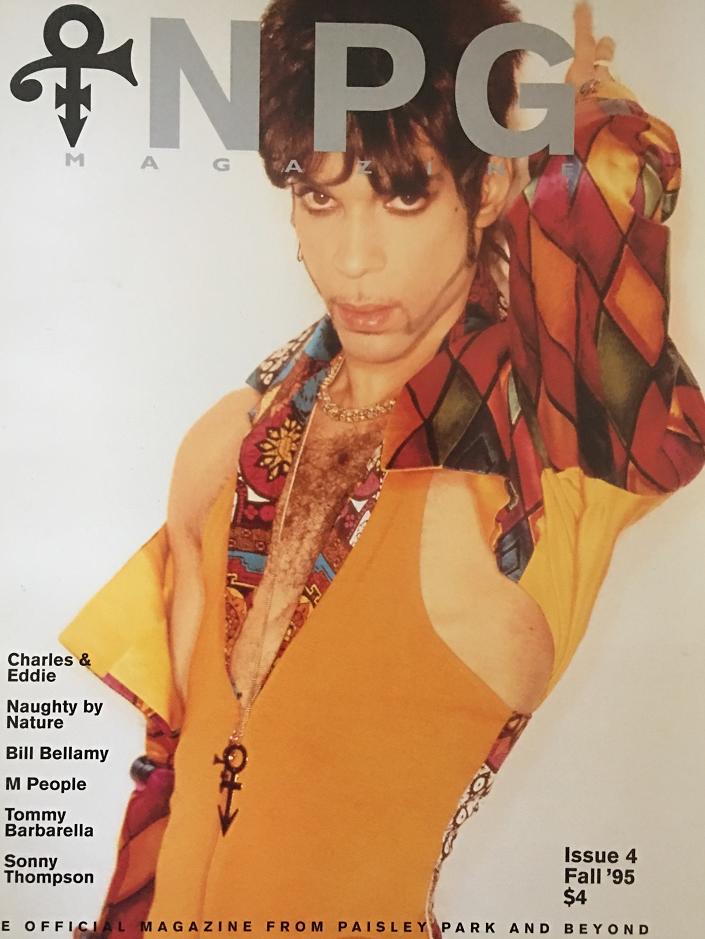

Mr. Holtje is a Brooklyn-based composer, poet, and editor. He worked under CultureCatch founder Dusty Wright on Prince's official mid-'90s magazine NPG. The art above is one of NPG's covers.