When James Agee noted in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, "You never live an inch without involvement and hurting people and fucking yourself everlastingly," he could have been describing the highly self-destructive Truman Capote to a T.

Best remembered today for the romanticized film adaptation of his novel Breakfast at Tiffany’s -- the Audrey Hepburn starrer -- and for his acclaimed mega-seller "non-fiction novel," In Cold Blood (1966), Capote is what might have happened if Fran Lebowitz had been born an effeminate gay boy with literary ambitions.

If you arrived too late on the planet to have been enamored by Capote's antics -- he did die in 1984 after all -- fear not. The joy he wrought and the outrage he often elicited is captured in Ebs Burnough's deliciously wry new documentary, The Capote Tapes.

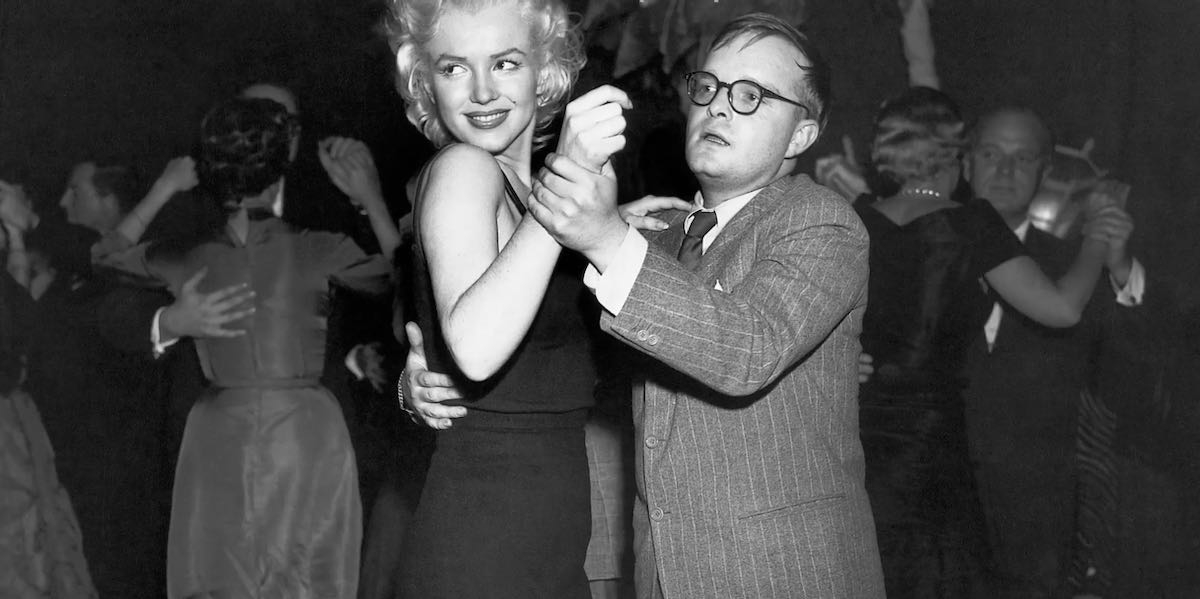

The inspiration for this project was the discovery of hundreds of hours of taped interviews that the late journalist George Plimpton conducted for a projected bio of Capote that was never to be. With these reel-to-reel chats with the likes of Lauren Bacall plus new remembrances (e.g. Dick Cavett), a plethora of photos, snippets of TV interviews, and random found footage, Burnough chronicles Capote from his early abandonment by his mother to his mail-clerkdom for The New Yorker. Then it’s on to his immediate fame on being published. That takes about fifteen or so minutes. What follows is Capote's embrace by the "Beautiful People;" his mingling with Marilyn Monroe, Mick Jagger, and the like; his trysts, some with married men; the film adaptations; plus his continued battle with homophobia.

Poor Truman! The gent, who was once America's most famous living author, never had the option of hiding in the closet. His whole being screamed "Queer!" at a time when gaining gay rights could not even be imagined. One "fan" even described Truman's first book, Other Voices, Other Rooms, as "the fairy Huck Finn." From his mincing presence to his immediately identifiable voice to the characters in his books, he did in fact take on the world . . . and his mother who never approved of his sexual bent even on her death bed.

As writer Colm Toíbín recalls on-camera, Capote finally accepted his identity to a degree. Toíbín imagines Truman saying to himself: "Well, this is who I am. You're the local gay. There has to be one, and I am he."

But was he an activist? A really brave soul? The Capote Tapes will probably convince you of that, although you might deem that the writer comes off as a highly flawed queer warrior, one running about in high heels made of steel. Clearly, there are no doubts about his literary talents. These are championed in the documentary as they are in The Gay & Lesbian Literary Heritage: "Capote's writing, especially the fiction and more direct autobiographical work, helped establish what might be called the quintessential homosexual writing style of the period, with clear links to the work of Tennessee Williams, for example." (You might also want to check out another acclaimed documentary that came out this past June, Truman & Tennessee: An Intimate Conversation.)

Capote, though, would have preferred a comparison to Proust, especially with his uncompleted novel Answered Prayers, chapters of which were printed in Esquire. This final work, as this documentary incisively displays, lost him most of his favorite socialite friends (e.g. Babe Paley) and appeared to increase his drinking and drug use, if in fact these pastimes of his could be increased. As an interviewee here notes, the book was "an early template for reality TV."

Apparently, for years and years, on yachts and off, the Housewives of the Rich and the Mighty told all of their darkest and most entertaining secrets to this puckish author, and then they were completely flummoxed when he wrote up these confidences with only the names changed. One blueblood even committed suicide because of Prayers. Hadn't they all read F. Scott Fitzgerald or Nathanael West? If you want your peccadilloes safeguarded, save them for your shrink or your priest, not your queer beard.

Happily, Burnough's film is not just satisfied with delving into Capote's psychological makeup ("What makes Truman run?"), his lovers, his lies, his "Party of the Century," and his friendly gropings, but also with what is it to achieve early fame in our society? What is it to be a serious writer?

"What was his special gift?" Norman Mailer is asked by Plimpton.

"Sentences," the uber-heterosexual writer replies. "He wrote the best sentences of anyone in our generation."

Mailer also recalls going into an Irish bar midday in New York City with Capote, one that was packed with beer-drinkers who all turned silent and stared at the sprightly elfin figure sauntering past them to a table in the rear. Mailer noted his own adrenaline was pumping away. He was expecting some nasty name-calling incident to occur along with possible fisticuffs. Capote apparently was unaware of the effect he was having, or he was so used to it and didn’t care. Nothing, however, happened, and the two major literary figureheads of their time just talked away for an hour or so to Mailer's surprise.

Truman often nonplussed his pals. One day he told a lovely member of high society that he loved her. "I love you, too," she responded.

"People don't love me," he retorted. "I'm a freak. People are amused by me. People are fascinated by me. But people don't love me."

Capote was both right and wrong.

(The Capote Tapes is having its World Premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival. Ebs Burnough’s doc will then open in New York City and Los Angeles on September 10th and within other markets a week later.)