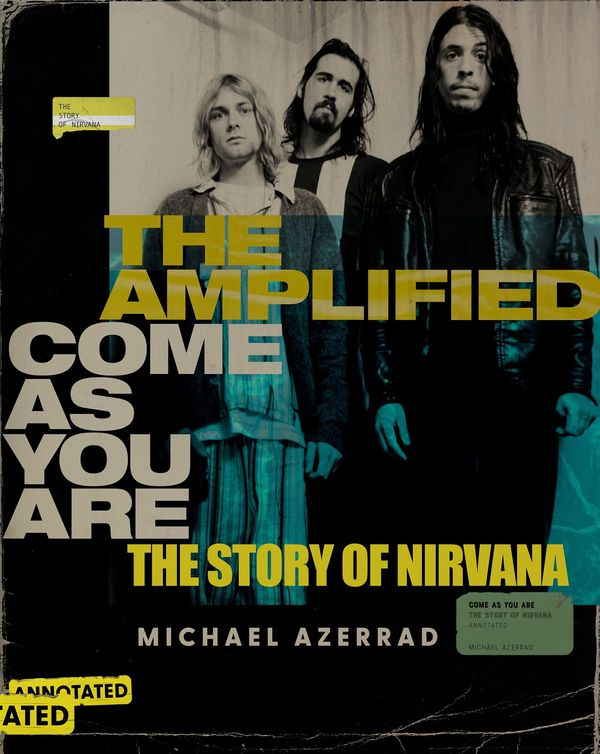

Michael Azerrad: The Amplified Come As You Are: The Story of Nirvana (HarperOne)

Is it okay to review a book in which I am thanked? And the author's been a friend for over four decades? Maybe if I reveal that stuff up front, like I just did…

Come As You Are: The Story of Nirvana was originally published by Doubleday in 1993 -- the year before Nirvana leader Kurt Cobain died. Azerrad had interviewed the members of Nirvana for a 1992 Rolling Stone cover story, and Cobain had approved of it enough that later in '92, when he and wife Courtney Love wanted someone to write a Nirvana book, they approached Azerrad, who of course said yes. There was some time pressure -- the book, it was eventually decided, had to be released in conjunction with the release of Nirvana's next album -- but Azerrad was nonetheless able to interview loads of people involved in the lives of the Nirvana members (including a whopping twenty-five hours of interviews with Cobain alone) and delivered a tome which has appeared on multiple lists of the best books on rock topics. In an age when rock albums regularly get expanded in anniversary editions, why not do the same thing with a rock book?

There are two ways of documenting a band: in the moment, or in retrospect. The Amplified Come As You Are is the best of both worlds. Anyone who follows Michael Azerrad on social media can see that he is strongly committed to making sure that assertions, received wisdom, etc. be fact-checked against reality, complete with citations. It turns out he's just as hard on himself. This thirtieth-anniversary revamping of what was the very first book on Nirvana ends up being about twice as long as the original version, and a lot of that additional length comes from Azerrad correcting himself. Much of what he is correcting comes from Cobain confabulating for comic effect or to pre-emptively stave off potential criticism (often deploying a tactic which Azerrad calls "smokescreening by exaggeration"), and flat-out lying about everything from his taste in music to details of his love life to, inevitably, covering up his heroin use. Courtney Love is guilty of image-burnishing as well, but is less of a focus, and Azerrad deliberately avoids detailing the many anti-Courtney stories while acknowledging that they're out there. She comes off as a complex person, intelligent and driven but undiplomatic, alienating people with her blunt behavior.

Most painful are the frequent foreshadowings of Cobain's suicide. Azerrad -- who calls himself an idiot multiple times -- writes, in one of the new bits, "It's excruciating to come across all the references to suicide in this book. But things like that can be difficult to see when you're right in the thick of it." Azerrad spends a considerable amount of space taking advantage of hindsight, which leads to an acute analysis of Cobain's psyche, especially his feelings of inferiority, the ways in which his self-defeating behavior reflects his ambivalence and his difficult youth, the ways in which he tries to have it both ways regarding ambition and approval, and the frequent foreshadowing of his demise.

Azerrad especially reproaches himself for his handling of the heroin topic. His most self-critical passage might be this one: "When Krist said, 'I was afraid of what I might see,' he probably spoke for a lot of people around Kurt: avoid confrontation, just get on with things, and maybe the problem will just go away. That's denial. I did that, too -- I was dimly aware that Kurt was doing heroin more than he admitted; I just didn't want to dig into it. It would have jeopardized my book. And I feared the wrath of their management and legal team… It would have betrayed the trust Kurt had for me -- but was it really trust? Or was it faith -- faith that he could play me, or at least that I would look the other way? Was it my place as a journalist to rat him out? Did I even know how to deal with such information responsibly and constructively? I just kept writing my Nirvana biography and left out the more sensational 'Kurtney' stuff."

On the other hand, Azerrad did get a fair amount of heroin discussion into the book, and he sometimes called out Cobain, as in this passage: "'I can't stand people who don't confront anyone,' Kurt says, seemingly oblivious to the fact that he himself is a prime offender in this regard." He also included Cobain making horrible threats of violence against some journalists who had offended him, and though Cobain apparently had no problem with those quotes being included, Azerrad clearly realized that they did not display Cobain in a favorable light (he refers to the "undeniable creepiness of the answering machine tapes"). One of the things I got from reading this new edition is a new appreciation for how well-rounded a portrait (warts and all) Azerrad delivered; true, things were even worse than he realized, but he still included much more negative information than most rock biographies done with the cooperation of its subjects deliver. (But not "authorized"; that is generally understood to include the subjects' right to control the text, whereas Azerrad's contract specifically disallowed that.) Yet he had to struggle with some difficult decisions: he had been told that Cobaine cheated on the urine tests he had to submit in order to keep daughter Frances Bean after Children's Services had taken her away from the couple, but he left that out of the book because "I was just not going to pursue it and perhaps be responsible for them losing their child again, maybe for good." I have never, in my three-decades-plus time in music journalism, had to make a decision with even a hundredth of the possible impact of that.

It's not all angst, though. Azerrad has a sardonic sense of humor that often comes out in passages such as, "So the real villains weren't people who never touted punk ideals -- it was the opportunists, the poseurs who hitched themselves to the indie community but didn't emulate its values. The villains were also those who originally embraced those ideals and then betrayed them. Someone had to police these people." It's no wonder that he shows sympathy for Love, who has a somewhat similar (albeit more overstated) sense of humor -- though he also, at one point, remarks on a quote of hers, "Actually, it's not penitence if your only regret is that you got caught."

Azerrad occasionally talks about the nuts and bolts of songwriting/music-making, such as Kurt's use of polytonality (using chords outside the key of the song), without getting especially technical even while explaining it well. Another example is how Cobain picks words that sound good sung more than working on making the lyrics make sense. This focus on picking words with vowels that work well in particular musical contexts is something that Burt Bacharach goes into detail about in his autobiography (which I highly recommend) -- that Cobain, barely musically educated and having learned songwriting through a combination of paying attention to others’ songs and seeing what worked in his own trial-and-error self-education, figured out by himself.

Do I find some faults in the book? Yes. There is a story about using a guitar drop-tuning, in which the lower of the two E strings is tuned down a whole step to D: "For 'Blew,' Kurt tuned down to what's called a 'drop-D' tuning, but before recording the song, the band didn't realize they were already in that tuning and went down a whole step lower than they meant to, which explains the track's extraordinarily heavy sound." This doesn't quite make sense. First, it's unclear whether Kurt or "the band" (Kurt plus Krist) erred. More to the point, when listening to the recording, it's clear that both bass and guitar are tuned down even further than another whole step, C, as they are both playing low Bs, so both bass and guitar were tuned down. That cannot have been an accident. It also is revealing that the guitar part is all riffs, no chords -- Cobain perhaps didn't want to (or couldn't) deal with figuring out chords with one string tuned differently than usual. Instead, this story seems like Kurt making up an entertaining explanation instead of going with the more mundane reality of the situation -- a tactic that Azerrad calls out repeatedly in the "amplified" sections of the book.

There are also contradictory passages regarding the Vanity Fair/Hirschberg article: "Hirschberg couldn't confirm either statement because they weren't true: Kurt was on record -- in my Rolling Stone cover story, for instance -- as saying that he'd started doing heroin long before he even met Courtney." And again: "…various factual errors throughout the piece would seem to compromise Hirschberg's accuracy. For instance, she wrote that Danny Goldberg was a vice president at Polygram Records, when in fact he was a vice president of Atlantic." Three other errors are mentioned in the same paragraph. But later, in one of the new passages, Azerrad refers to Vanity Fair as "a major magazine with a diligent fact-checking department."

But obviously a 618-page book that only contains two inaccuracies has a pretty good batting average. Even Homer nods, as the saying goes.

Or three: Azerrad states that Lemonheads' It’s a Shame About Ray is merely "a decent album." I know that the following Lemonheads release contained the group's biggest hit, but It's a Shame About Ray is by far my favorite Lemonheads record to put on. De gustibus non est disputandum. I kid, I kid.

But enough of my frivolity. A final, post-Cobaine-suicide, chapter was added to a reprint of the original book; I had never read it until now. Anybody who can get through it without shedding tears is probably too dispassionate to have appreciated Nirvana's music. But the most stunning thing about the book in its present state is that it seems like it would be a good read even for someone who doesn't care about Nirvana, because as now presented, it is a fascinating examination of a band's rise and demise; life and death, personality flaws and mistakes and the ways in which someone in the public eye deals with them; the psychological journey of that band's leader, and for that matter of the other players; the intricacies of the music business at a crucial turning point; and the tricky issues a journalist must face in the moment and the later reflections on those issues. Even, I would say, the psychological journey of that journalist: Azerrad is unabashedly emotional at times, especially in the last few chapters.

Given the time of year, this book will make for an excellent stocking-stuffer -- if it's an XXL stocking.