I could never fathom why some folks in the past didn't take to the French. I, for one, was already a Francophile by my late teens. Locale: the Bronx in the '60s.

Since then, Cocteau, Sartre, Collette, and de Beauvoir, in battered paperback formats, have found permanent residence on my shelves, which have since been shuffled along to another borough. (If you look hard enough, you'll also find a Céline or two. I know. I know. He moved in before the Cancel Culture arrived.)

All of which reminds me of being 20 and finding myself meandering without direction through the arrondissements de Paris, stopping only to imbibe a bit of caffeine at Les Deux Magots, as I awoke to all of the possibilities of l'amour that might one day greet me.

Sadly, one-night stands aside, l'amour has mostly sidestepped me, but that is not France's fault, so I will not forgive D.H. Lawrence for saying of the country that gave us Camembert: "I would have loved it—without the French."

Nor Billy Wilder:" France is the only country where the money falls apart, and you can't tear the toilet paper."

Nor Fran Lebowitz arguing the French are "Germans with good food."

Philistines all.

This brings us to the 29th Rendez-Vous with French Cinema presented by Unifrance and Film at Lincoln Center. Twenty-one features that until now were unseen upon our shores. "Is there a theme that unites these descendants of Breathless, 400 Blows, and The Mother and the Whore?" you ask. Why not turn again to Jean Cocteau, who remarked, "Between the life we live and the unlived life is the love we have never formed."

These features often showcase an assemblage of characters fighting to keep their "form" of love alive as the powers-that-be seek to break up their families, beat them into submission, tempt them into selfish immorality, or go bonkers with their genetic makeup.

Take Auction/Le livre des solutions. Pascal Bonitzer, who co-wrote the screenplays for Paul Verhoeven's tongue-in-cheek Sapphic nun-fest Benedetta (2021) and Catherine Breillat's steamy May/December romancer, Last Summer (2023), here delves into a modern art-world dilemma: who is the rightful owner of a work of art when the rightful owner is long deceased?

As director here, Bonitzer fashions a caustic look at a highly regarded auction house's underpinnings, creating a landscape where virtue is not a ready resident.

The tale begins with André Masson (Alex Lutz), a seasoned auctioneer, being made aware an Egon Schiele painting, one missing since 1939, is supposedly hanging in the home of an innocent working-class chap (Arcadi Radeff). Masson's first reaction is disbelief. When the work's authenticity is established, he knows what the sale of such a work can mean to his prestige and his company's bottom line, but can he sign up the owner? Of course, but what happens when it's discovered the work was looted by the Nazis from a Jewish family whose heirs might still be alive in the good ol' U.S. of A?

Engrossing, timely, and with a lead character whose motto is "being hated is good for the job," Auction doesn't exactly argue there's more to life than just cash flow. Nor does the film insist for quite a while that leading a well-balanced life with more than a dollop of romance is ideal. But by the end, Auction does make a rather strong case that there are moral ways of winning, ways that just might take a little more effort on everyone's part.

If you're in the mood for more light-hearted fare, Nathan Ambrosioni's Toni takes a fatherless family of five and reveals how les enfants terribles' growing pains affect their fortyish mom, who's experiencing quite a few aches of her own. What might seem overly familiar plot-wise is really quite entertaining, thanks to the scintillating Camille Cottin as the fretful maternal figure. You'll recognize Ms. Cottin from Netflix's Call My Agent!, the witty cult series that gained extreme popularity on our shores during the Covid era.

Some background: Toni, who became a pop star as a teen due to her manipulative stage parent, happily gave up fame for motherhood. But now, with a dead husband, little cash on hand, two teens readying for university, a Christmas tree dropping all its needles, a coming-out or two, plus the never-ending laundering, dusting, and cooking, Toni realizes she wants more. Maybe the time has come to carve out some me-time. But without any skills, will the workforce welcome her? Maybe she can attend a university herself. How about becoming a teacher? But what can she teach?

Her own mother laughs heartily at the notion. Toni's brood looks dismayed. "What about us?" they question. Oh, no! Has life really bypassed her? Has she paid too high a price for caring too much about everyone else for too long?

With solid comic timing sprinkled with momentary angsts and cosmic tribulations, you wouldn't be surprised if Michelle Obama was an inspiration here. After all, the former First Lady is the one who instructed, "I want [children] to see a mother who loves them dearly, who invests in them, but who also invests in herself. It's just as much about letting them know . . . that it is okay to put yourself a little higher on your priority list." That's Toni in a nutshell.

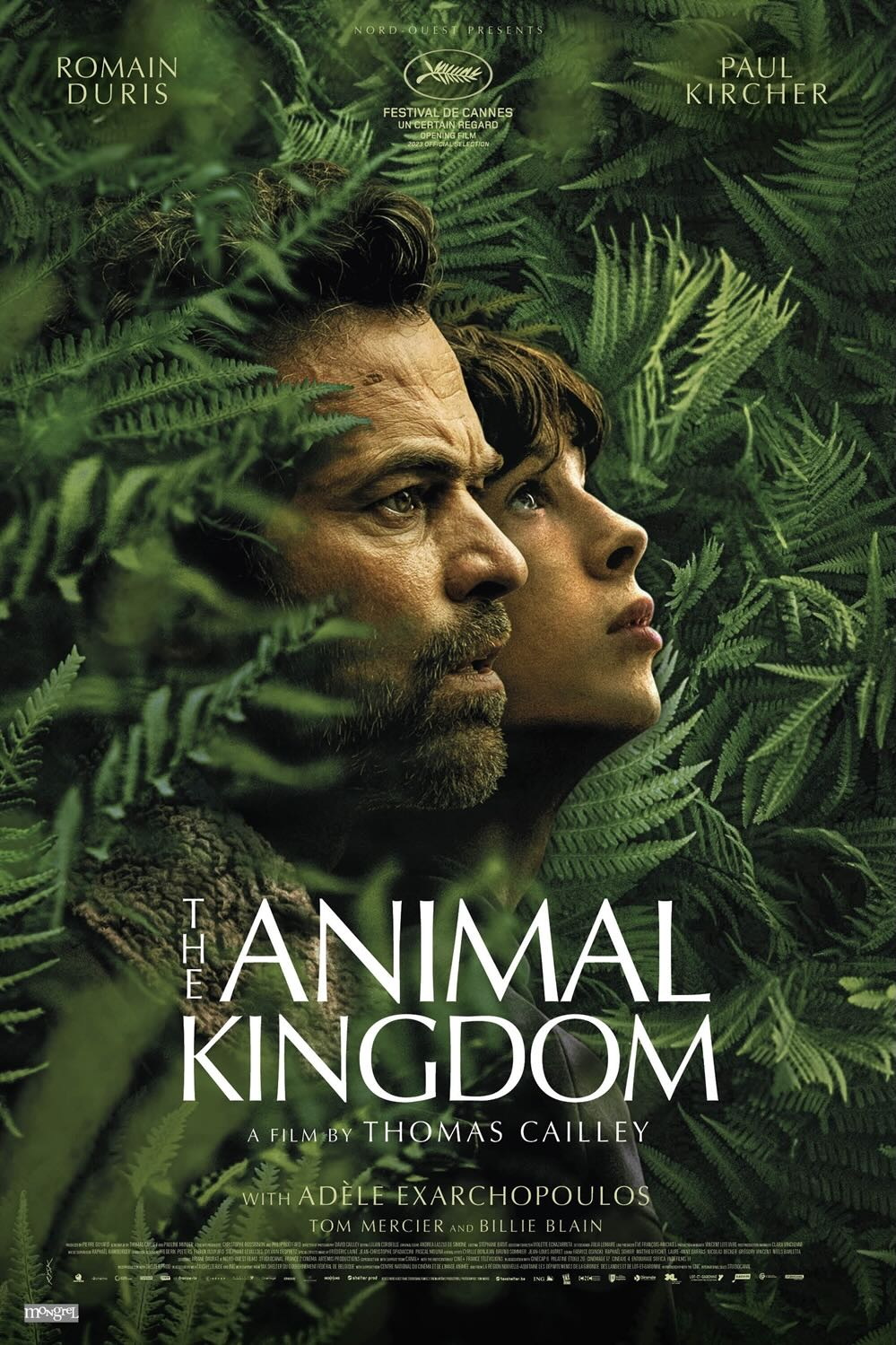

There's no nutshell, however, that can contain one of France's most highly awarded sci-fi, epidemic-inspired offerings. Boasting more than a twinge of Cocteau's whimsey within its carryings-on, Thomas Cailley's The Animal Kingdom has already garnered 25 nominations and awards, including Best Motion Picture, Best Director, and Best Visual Effects from various festivals. Here is, at heart, a love story between father and son that begins and ends in a car with the eating of potato chips.

While stuck in traffic on the way to visit his wife in a hospital, François Marindaze (Romain Duris) berates his son Émile (Paul Kircher) for feasting on the aforementioned salty snack.

François, while lighting a cigarette: "Eating is like talking. It defines you as a human being. Even better, it defines how you exist in the world."

Émile: "And eating chips means I don't exist?"

This chat then melds into the difference between disobedience towards a parent and committing transgressions against a system, but before this philosophical combat can rise to another level, there's an attention-grabbing incident on the road ahead of them. A "man" with giant wings has burst through the back doors of an ambulance and is trying to escape "its" guards.

(Pronouns play an important part here because you must decide whether a human who is turning into a creature loses the humanity engrained in his cis-pronoun.)

For father and son, this event isn't all that shocking because Émile's mom, Lana, has already started transitioning into something rather ursine.

What follows is a rather awe-inspiring adventure that continues in a small French town, where folks who are "infected" are being transferred. Yes, some rather nice souls who have mutated into octopi, praying mantises, lizards, and so forth are suddenly finding themselves the victims of extreme bigotry. Hate speech first, guns next?

And if that isn't enough, what if you are a teen lad ready for romance and discover you are growing claws and fangs? There are matters that breath mints can't resolve.

Beautifully shot while perfectly cast and helmed, Animal Kingdom is an exuberant example of humane cinema at its best. At Cannes, Cailley explained that the idea of the film "spoke to me because it allowed me to touch on subjects that interest me, namely the body, our relationship to difference, the issue of passing on the worlds we want to pass on, but also the relationship we have with everything that's alive including things other than our fellow humans."

Moving on to Michel Gondry's The Book of Solutions, this wackadoodle tale of the world's least-talented director can't help but remind you of the trans-Atlantic furor over the Gallic fondness for a certain comedian. The New York Times' Agnès C. Poirier stated this lack of cultural agreement best in her 2017 article, "Why France Understood Jerry Lewis as America Never Did." She writes: "While some Americans felt embarrassed by this contortionist comic, the French embraced Mr. Lewis's humor as both an abstract art and social satire of American life."

In Solutions, director Marc Becker (Pierre Niney) pilfers his unfinished film from its producers after they decide to cast him off the project. He scuttles to the remote countryside, along with his harried editor and assistants, to create a frighteningly incomprehensible masterwork that spurs on mass slumbering.

The archetypal Jerry-Lewis moment here is when Becker, whose knowledge of music is minimal, tries to record his film's score with a ragtag bunch of musicians without a rehearsal, let alone a score. Physical, reverberant goofiness conquers the moment with low-comedy stylings. Not surprisingly, Mr. Becker might just become a town's mayor before the end credits roll. (Surprise cameos: Sting, and if my notes are correct, George Clooney.)

Other fest highlights spotlight French star Virginie Efira in three roles in two offerings. Is she France's Meryl Streep? She certainly has enough award nominations and winnings to be in the running. Add to them her memorable crucifix manipulations as a nun shocking the crowds during the Black Plague, and you have enough reasons to tack her poster on your bedroom wall.

In Delphine Deloget's emotional wringer of a tale, All to Play For/Rien à perdre, Efira is Sylvie, a late-night bartender with two sons, the youngest of whom burns himself cooking up a batch of fries while she's off maneuvering drunks about. That is a no-no for the Child Welfare folks. So, for the rest of this engaging, no-holds-barred look at the working class and their battles with the State and with themselves, Sylvie tries to regain custody of her child, who has a fondness for a live chicken.

Valérie Donzelli's Just the Two of Us has Efira playing twins Rose and Blanche. Rose, rather strong-willed, doesn't have much of a story arc, but Blanche is a whole other story. This school teacher falls for the attractive, intense Grègoire (Melvil Poupaud), who isolates the naïve gal, slowly trying to control her every move. Extremely jealous, he calls her up every hour to discover her whereabouts. He stalks her, impregnates her, uses the child as leverage, screams, and eventually gets physically abusive. No wonder Britannicus is quoted: "I even loved the teardrops I made her shed."

By the end of the Two of Us, I checked myself for black-and-blue marks. But have no fear; by the end of every Efira feature, the heroine is able to walk down the hall or up the road with her head held high . . and no neck brace on.

Also of note is Robin Campillo's latest feature. You might be familiar with his takes on France's ACT UP movement (BPM: Beats Per Minute (2017)) and the problems that arise with loving a male hustler (Eastern Boys (2013)). With Red Island, he recalls his childhood in Madagascar in 1971 as the French were packing up their final colonial base on the island to the glee of the native inhabitants. As one notes: "Have you noticed whenever a white guy sleeps, we breathe more easily."

Campillo employs a French child's gaze to observe his parents' petty jealousies, the community's racist reactions to interracial coupling, and the anger of the Madagascans: "For twelve years, we have been independent but under France's thumb."

Most memorable scenes: prostitutes in rebellion, a household battles a wasp in its bathroom, and the final shot of a white family's attempt to take a photograph of themselves in a land where they were so "happy."

(The 29th Rendez-Vous with French Cinema was produced by Unifrance and Film at Lincoln Center. This is an annual event. To check up on all the offerings of Film at Lincoln Center, check out the organization's website: https://www.filmlinc.org/)