At what point does imitation become homage? Does “homage” even figure in when the hallmarks of a genre master’s style become tropes, and supply a well of motifs for young filmmakers to dip into, even though they may have no idea where those tropes came from? They’re not nodding to the masters so much as breathing the air that they provide. And in this age where the parameters of plagiarism have become hazy, is it invalid for those young filmmakers to use those tropes to craft a personal statement?

These thoughts came to mind while watching Somnium, a new film that presents itself as psychological horror, but gets at something much more interesting.

Starry-eyed smalltown Gemma arrives in LA to become an actor. She takes a job in an experimental sleep clinic called Somnium, which promises to literally make their clients dreams come true. Clients sleep in sensory-deprivation pods while Somnium technicians mine deep-seated dreams of success either to be achieved, or to implant the belief that they have already been achieved (Gemma questions the ethics of the practice: “Does it actually change their reality or just their perception of it?” and her coworker Noah replies, “What’s the difference?”)

Gemma goes about her life, working, auditioning, and in flashbacks relives her breakup with Hunter, a talented but unenterprising musician. Strange things start to happen to Gemma at home and at work: suspicious noises, ominous shadows, and a menacing pale figure.

Depressed and lonely, Gemma finds an angel in the back alley of an arcade: the mysterious Brooks, who offers to guide her budding career. Is he a talent agent or a devil? Alone in the nightshift, she discovers odd selfie videos of Noah, who appears in them to victimize women in Somnium’s sensory deprivation chambers. Additionally, there is the prospect of an “accelerated dream program” called Cloud Nine that forces clients to confront desires and motives.

Writer/director Racheal Cain cites Wes Craven as an influence—and one can see it, especially in The Nightmare on Elm Street—but David Lynch is clearly the template. Though set in the present day Somnium has Lynchian flourishes of the past: furtive meetings in diners, outdated computers, boyfriends styled on James Dean. Gemma gives a stunning audition á la Mulholland Drive. Gemma’s apartment contains a dark hallway which suggests a portal to hell, as in Lost Highway. A bar band is even named “Twin Peaks.”

Which is not to accuse Ms. Cain of imitation, or even homage. She uses familiar tropes, established longer ago than she’s been alive, to tell a story that questions her own motives as an artist. Gemma is her surrogate. Why want celebrity? At what cost? Why is Gemma so willing to sacrifice what she loves and debase herself in order to get fame? Ms. Cain comes to some unique and intriguing conclusions in Gemma’s trajectory.

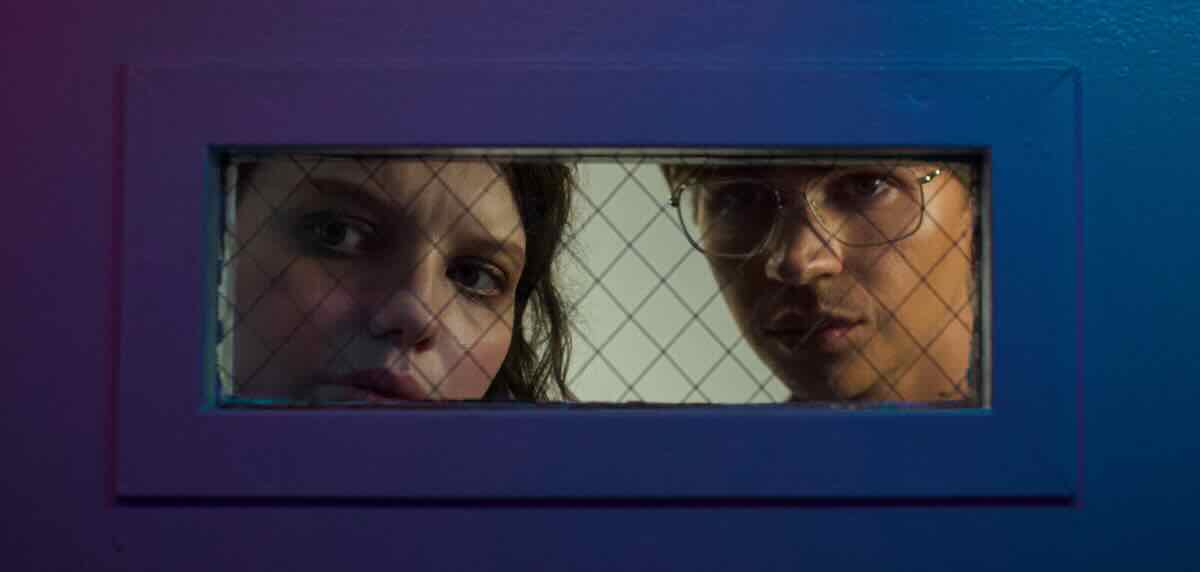

As Gemma, Chloë Levine gives a layered performance, going convincingly from innocent to desperate. As comically innocent as she appears in LA, in flashback she shows realistic passion with her boyfriend Hunter, played by an equally fine Peter Vack (Ms. Levine’s voluptuous features contrast nicely with Mr. Vack’s lean look). She is uncertain in her growing reliance on the punk-coiffed and hedonistic Brooks (played by Johnathon Schaech; good to see him again) who challenges her to become her true self. Will Peltz as Noah and Clarisa Thibeaux as Olivia, Gemma’s enigmatic coworkers, also do admirable work.

Besides her well-chosen actors, Racheal Cain’s vision is ably realized by the production design of Olivia McManus, the score by composer Peter Ricq, and Lance Kuhns’ cinematography.

Ms. Cain’s direction is succinct. She lingers on settings for a few beats more than usual after characters have left the frame, allowing us time to fully consider what we’ve seen. Is it innocuous or sinister? She peppers her horror-centric scenario with big questions: are we following dreams or are dreams following us?

Am I reading too much into this? I don’t think so. Ms. Cain has said the idea for Somnium has been simmering for years. Either way: if Racheal Cain followed the David Lynch tropes just because they’re there, she artfully honors the canon. If they bubbled up from her subconscious, even better. Maybe they came to her in a dream.

_____________________________________________________

Somnium. Directed by Racheal Cain. 2024. From Untold, Rabid Rabbit Films, and Allred. 92 minutes.