Making its American premiere after originally opening in Lisbon at the National Theatre D. Maria II in 2016 under the direction of its author, Mickaël de Oliveira, The Constitution marks the first production of Saudade Theatre, an organization dedicated to introducing Portuguese theater to an American audience. While saudade refers to a profound nostalgia or melancholic longing for something or someone absent, the company's challenging debut play represents the product of addition rather than absence: in Saudade's words, a "meeting between an European aesthetic and the American theatre culture." With The Constitution, this cross-cultural conjunction produces complex results from a simple premise.

The elegantly spare conceit of Oliveira's play is that four people have been locked in one building together for six days (a perhaps Biblically allusive span of time) with the charge to write a new national constitution. They have been chosen by the government for this task following, the audience is told in a prologue, a period of great sociopolitical upheaval caused by the 2008 financial crisis, started right here in the United States. They are allowed no books, reference materials, or outside contact; whatever is produced will be entirely the creation of the minds of these three men and one woman. The chosen four, Diogo (Diogo Martins), Filipe (Filipe Valle Costa), Pedro (Pedro Carmo), and Maria (Maria Leite) are actors, actors about whom we don't know much besides that Diogo once belonged to the Communist Party and that Filipe and Maria once had an affair. Such opacity seems appropriate in a play in the first section of which Filipe suggests that Diogo pretend that he is in a Brecht play, to "first embody and then disembody" and "if you can't be yourself, just be some other crap, a character from beginning to end." The audience is also told at the start that what they are watching is a reenactment of the six days in question (each corresponds to a section of the play), adding another layer of detachment, with actors playing actors who are playing other actors.

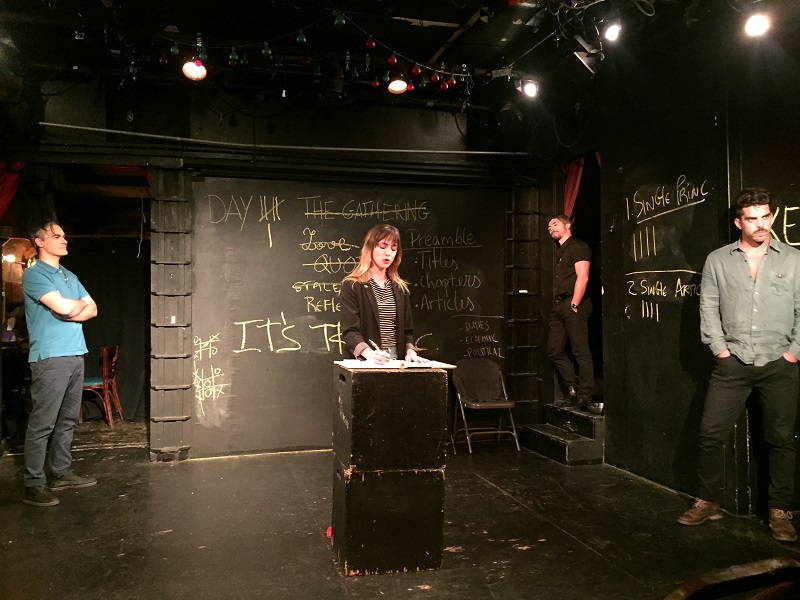

This "reenactment" is also set in a theater, and the production leaves the backstage area open to audience view, enacting a further Brechtian exposure of the theater's machinery of illusion. (We are reminded, too, at one point, that we are watching a translation of a reenactment, when a character remarks that a pun doesn't translate to English.) This degree of metatheacricality asks a lot of its actors, and (the real—"real"?) Martins, Valle Costa, Carmo, and Leite meet the challenge, creating a compelling and sometimes uncomfortable sense of what it would be like to be commanded to complete a surely impossible task for which one is seemingly unqualified; all four perform the varied, sometimes (especially in Diogo's case) sudden emotional shifts and the clashes of wills and personalities with such vigor that some non-mimetic moments take a few seconds to register as a part of the performance.

After some arguments about the constitution's length and goals, including whether democracy remains the best option with such low voter participation, the group more or less agrees that their aim is to totalize common experience within a single article, using a singular principle based on a single word that is itself more complicated than it may first appear. Before this decision is even reached, we already witness the difficulty of avoiding the temptation to recreate what already exists or has existed (to use, for example, Diogo's memory of the old constitution as a model). The play also subtly establishes a sort of mirroring of the personal and political, their histories and repetitions, substituting the couple for the more common family as a microcosm of the state, a reflection that becomes more pronounced over the course of the narrative. Ultimately, the interpersonal becomes just as much a text with the potential to be rewritten as the national (and, perhaps, the subject as much a repeated archetype here as an individual). Even the building becomes a text, as the actors use the black box walls as a giant chalkboard.

The Constitution is in many ways a play of ideas and of debate. The actors disagree over whether images or words are more concrete, with the suggestion that the constitution should follow the model of IKEA, which sells us the fantasy of being competent builders through its graphic instruction manuals. They wonder whether a concept's opposite or contrast is necessary in order to recognize that concept. They spend an entire, delightful section trying to define the single word undergirding their single principle through quotations while, in a nod to an acting exercise (or, more darkly, the conch in The Lord of the Flies), tossing a ball around to determine who speaks next. They even take Filipe's early advice about characters and inhabit the personae of Jean-Paul Sartre, Bertolt Brecht, Hannah Arendt, and Pier Paolo Pasolini (resulting in actors playing actors playing actors playing philosophers and intellectuals). While the actors abandon these characters, the multiple identities are not completely disentangled for the rest of the play, offering another angle on the theme of historical repetition. This kind of disruption and instability additionally appears in, for example, the multiple instances of fourth-wall breaking and a scene in which the characters deliver narration of what would normally be other characters' lines, amplified over techno music that eventually gives way to Wagner's "Prelude to Tristan" and "Isolde" (another pattern of/for Maria and Filipe?). This formal disruption itself breaks down further, ending in recorded, disembodied dialogue that again plays with a Brechtian sense of alienation and detachment. The characters create a case for actors as potential legislators: because actors know so well the words of others, and given their chimeric ability to become someone else, they may be better qualified than almost anyone else, but as these actors remind us, they are real people underneath their characters. When Filipe-as-Brecht is telling a story about his past love life, his voice and accent change part way through: has this become the actor's story? The actor portraying the actor's? Does it matter?

In the climax, Maria records the others' dictation of the final article, which they wish to create what they call an economy of giving, but when she has finished, she proves, shall we say, resistant to what she has written there. The Constitution offer easy answers for neither its characters nor for its audience. It begins by orienting the audience so that it can begin to subtly and later overtly subvert and challenge that feeling of ontological security. The play's sense of humor and the cast's performance ensure that the production's vertiginous conceptual experimentation and dense web of referentiality are entertaining to watch. For Saudade Theatre, The Constitution is a compelling founding document. - Leah Richards and John Ziegler