Although Frank McCourt will be remembered as a writer, that career, begun in retirement, eclipsed his lifetime's labours as a teacher in New York. His memoir of a flea- and rat-infested childhood in 1930s Limerick, Angela's Ashes, seemed to annotate an earlier, Dickensian kind of poverty, and was largely responsible foe the industry known as "the misery memoir."

His was the first, but few that followed in his wake were as refined, and as eloquent, as his particular distillation. In a debut, unflinching and unrelenting, the classic combination is harnessed. A down-trodden Irish mother, a drunken patriotic father, dead infant siblings, and the uncaring influence of the Catholic church. It proved an unlikely but lasting success, spawning a film adaptation, starring Robert Carlyle and Emily Watson, and earning McCourt a Pulitzer Prize and an invitation to the White House. Its honesty also fired the derision of some, who bemoaned him a traitor and a fantasist.

His version of Old Ireland proved an unwelcome ghost in the new country, aided by European grants and a sense of liberalism, but the past casts a longer shadow, and he never faltered in the face of such antagonism.

McCourt was born in Brooklyn in 1930, but his mother, fleeing the Depression, returned home, and into more problems in Ireland, than those she'd abandoned in the States.

"It was of course, a miserable childhood; the happy childhood is hardly worth your while. Worse than the ordinary miserable childhood is the miserable Irish childhood, and worse yet is the miserable Irish Catholic childhood."

This eloquent honesty was always going to alarm the the sententious, a trait so riddled in the Irish, it could almost pass as a indigenous characteristic. McCourt wasn't a killer of sacred cows, he merely wrote of things that rendered them less than divine. He portrayed his father as "alcoholic, wild man, great patriot, ready always to die for Ireland" but who usually landed home drunk and penniless, eventually abandoning the family completely, which fueled the author's intolerance of a picture postcard nostalgia.

He admitted that "the central event of my life was my father's alcoholism" and that "poverty deprived me of self-esteem, triggered spasms of self-pity, paralyzed my emotions, made me cranky, envious and disrespectful of authority, retarded my development and made me unfit, almost, for human society."

If he was unflinching in his treatment of his childhood, he was equally unflattering in his portrayal of himself. His was a strange democracy of honesty. Angela's Ashes was a book created under duress. He found writing it a cross between catharsis and insanity.

"I was a madman when I was writing, weeping and laughing. It was grinding." It also proved a runaway, if unlikely, success. Translated into seventeen languages, it made McCourt, then 66, wealthy and famous.

He wrote with bemusement, "I became Mick of the moment, a media darling, a geriatric novelty with an Irish accent."

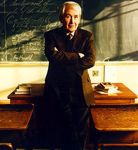

He followed it with Tis, his story of his life in America, and then in 2005 with Teacher Man, about his experiences in New York schools. Angela's Ashes ends with McCourt, aged 19, returning to New York. Drafted and sent to Germany, his GI bill, whose provision meant education for returning servicemen, resulted in his graduation, and in work as a creative writing teacher.

By his own admission, his past had left him a difficult presence, but he was an inspiring teacher, and a frustrated writer. His fame was a perverse rendering of celebrity, an ordinary life as the passport to success.

Frank McCourt will be remembered for remembering what many wished he had forgotten. There was scant dignity in his impoverished childhood, and he told it accordingly, without allowing time to diminish the blows. His Ireland was dirt poor, and he rendered it so. He may have upset the purists, but what they seek to ignore is where the truth resides.

He brought a literary grace to the graceless and the usually forgotten. His wasn't the only miserable Irish childhood, but he was one of the first to honestly say how unbearable it was.