Music and Sex: Scenes from a life - A novel in progress (first chapter here). Warning: more highly graphic TMI.

A weekend of fruitless fretting almost led Walter to agree that Martial had the right idea and the show should go on with no guitarist, and with just Walter on keyboards, but really all he'd come up with for sure was a new band name -- The Living Section, for the Wednesday arts portion of The New York Times. The other guys all agreed that was an improvement. However, he couldn't bring himself to propose to them what, in his head, he had dubbed the Martial Plan.

The thing about the band was, it had to be fit in between all the stuff that going to college was actually about, such as attending classes. So on Monday, it was back to the usual schedule, which meant one of his favorite -- because it was both easy and about music -- classes, Music Humanities. The Spring semester was taught not by Professor Hatch, but by Ellen Harris. Fortunately she also had a sense of humor; everybody laughed when she related her story about being injured by a prop pistol onstage during an opera performance, and on being asked in the emergency room, "Where were you shot?", answering, "I was shot in the opera."

Partly because of his height, Walter tended to sit in the back row of his classes. During Music Hum, this often resulted in Rachel Lofsky sitting in front of or alongside him. Hesitant and uncertain when called on in class, perhaps she was hoping to escape notice in the back, but she often slipped in just before class started, by which point the back row had been filled. Her preference for low-cut jeans meant that Walter was often treated to a view of her ass crack. He was reminded of the evolutionary explanation that he had read about in a sociology book saying that breasts evolved to mimic buttocks when our ancestors began walking upright. However true that might be, butt cleavage didn't excite him as much as breast cleavage did. Hence, sitting alongside Rachel was better, as she had a most ample bosom, which Walter enjoyed viewing in profile. Sometimes, depending on the angle at which she sat and what she was wearing, he saw some of that cleavage as well.

After class had let out that day and he was walking down the stairs in Dodge Hall wondering what to do about the band, Rachel caught up with him, saying, "Walter, do you mind if I ask you a question?"

"Go right ahead," he responded.

"You seem to know so much about music. Would you tutor me in Music Hum? I'll pay you."

"Sure, that sounds like fun." Walter would have said the same thing if she'd asked him to scrub her floors.

"Thanks! When are you available?"

"Tuesday and Thursday afternoons are good. Weekends, if I don't have something planned."

"Tuesday's good for me too. Four PM? "

"Okay."

"Can we start this week?"

"Tomorrow? Sure. I'll meet you at the listening room in Dodge."

"Oh, I don't want to do it there. It would be embarrassing. Can you just come to my apartment?"

"Have you got a cassette player?"

"Yes."

"Good. I'll bring tapes."

Rachel lived off campus. She gave Walter her address (corner of West End Avenue and 106th Street) and also her phone number, "because you have to call from the payphone on the corner in front of the liquor store and then go to the 106th Street side and I'll throw my keys down to you so you can let yourself in."

That evening, he made tapes of the repertoire that they were listening to in class. The next afternoon, a sunny and warm day, he walked down Broadway and kept going onto West End where Broadway curved and West End started. Rachel tossed her keys down to him wrapped in a sock. After he'd walked up to her fourth floor apartment, starting to sweat a bit by the end, he saw her standing barefoot in her open doorway, attired in cutoff blue-jean shorts and a button-down shirt knotted above her midriff.

He followed her down the long hall of the shotgun apartment, all the way to the back, a large and sunny corner room. "Have a seat," she offered, pulling a chair out from a small desk against which an electric bass was leaning. There were no other chairs in the room; she sat on the mattress on the floor.

He turned the chair to face the bed, sat, and got straight to the point. "Where's your cassette player?" He didn't see one in her stereo. Her big brown eyes locked with his and she answered, "It's in my desk." She leaned forward, and suddenly he was hyperaware of how her cleavage increased when she did that. Her long, dirty-blond hair swung next to him. Walter felt an erotic charge from her closeness.

Rachel opened a drawer and pulled out a portable tape recorder. Walter noticed a large rubber penis in the drawer. Rachel noticed him noticing it. "I'm so embarrassed you saw my dildo!" she exclaimed. Walter's impression, though, was that she wasn't acting embarrassed at all, and her next words seemed to confirm that: "If I'm tense, I can't concentrate, so I need to relax myself at least once a day."

Walter felt a frisson of shared naughtiness. "Me too. But I have a roommate, so I don't get to do it as much as I'd like."

"That's awful! Do you want to do it right now?"

"It seems like I always want to do it."

"I mean, will you do it for me now? I'd like to watch."

Walter was momentarily speechless. She filled the silence by saying, "I'll do it too, we can watch each other."

That was too good an offer to turn down. "Okay!"

Rachel untied and unbuttoned her shirt and pulled it off. She was wearing a plain white bra. Walter sat transfixed as she reached behind her back and unhooked the bra, shrugged her shoulders forward, and slid the straps down her arms. Her bounteous mammaries hung in front of his face at eye level, hypnotizing him. Soon her pants dropped to the floor as well. Surprisingly, she'd had nothing on under them. She reached back into the drawer and pulled out the flesh-toned dildo. She unrolled a condom onto its head as she stepped back and sat on the edge of the bed.

"Aren't you forgetting something?" she said.

Walter unfroze from his bedazzled trance and stood, quickly donning his clothes. He dropped them on the metal chair and sat on them, facing Rachel. She smiled at him and opened her legs. She ran her fingers down through the profusely hirsute patch there, spreading the light brown hairs apart, and rubbed the dildo head up and down the revealed lips, then pushed it between them. Walter felt his erection intensify its hardness, pointing straight up. He put his hand on himself and gently stroked it.

Until he'd come to college, Walter had masturbated by grinding his crotch against a pillow. Lately he'd been experimenting with the new skill of whacking off with his hand while in the shower. It was still a novel feeling, made more so at the moment by the fact that he did not have warm water and soap to provide lubrication. Not that this lack was any impediment, not with a voluptuous naked woman in front of him stuffing a fairly large dildo into herself. Rachel started moaning, all the while staring intently at Walter's crotch. Her hand moved the artificial dick in and out at a faster pace, and her breasts jiggled. Walter could see her juices glistening on the plastic rod. He suddenly felt proud of himself, proud that, as he saw it, his cock could help inspire such a reaction. As he stroked himself, his thumb rubbed the pre-come oozing from his cock around the head.

He wanted to touch Rachel, but feared endangering this magical moment. She had only spoken of watching. Somehow that suppressed longing intensified his sensations.

The volume of Rachel's moaning increased, and one of her legs began to twitch. She lay back on the mattress and pumped harder. "I'm coming, I'm coming," she whispered hoarsely, arching her back up from the mattress, her weight on her shoulders. She squeezed her legs together and shuddered repeatedly.

After a minute she turned on her side to face him. "Come for me," she urged. "I want to see you jizz."

Walter tightened his hand around his cock and stroked faster. Usually his eyes were closed when he did this in the shower, some fantasy image held onto in his mind, but now his eyes locked with hers for a moment. Then she looked back down at his cock, and watching her watch him pushed him over the edge. A long rope of white liquid shot out towards her, splattering onto the wooden floor just short of the mattress. "Oh yeah!" she exclaimed. Then came another, travelling half as far, and then shorter spurts, then dribbles as he milked the last drops from his penis.

"That was great!" Rachel enthused. She grabbed a box of tissues from the night table and wiped up his jism. When she tossed it in her battered metal wastebacket, it made a wet thump. She stripped the condom from the dildo and dropped it in the trash as she returned the dildo to its drawer.

It was an old floor, with gaps between the wood planks. Walter was sure some of his sperm had escaped into the cracks, his genetic material thus to reside there for – how long? Was this a sort of latent immortality? Contrarily, he'd learned in the previous semester of Lit Hum that in the Middle Ages, orgasm was called "the little death." When sperm left your body, did part of your soul travel with it? Did he think these nutty thoughts only because his penis had just borrowed blood from his brain? Would he be able to talk about music intelligently?

As it turned out, he would. Walter got dressed again and Rachel put her shirt back on, but only her shirt, though it was long enough when not tied to obscure her groin when she leaned forward. Walter then spent forty minutes playing the musical examples on his tapes and giving her practical advice on recognizing the composers, following the structure of a sonata-allegro movement, etc. He kept his eyes on the tape recorder as much as possible to avoid distracting himself, though when they were quiet while listening, he was wondering what his next move should be, because he was utterly smitten.

Finally the last tape was finished (obviously he hadn't been playing them in their entirety). It was 5 PM, so he thought a dinner invitation would be natural enough. Maybe it was, but it didn't work.

"Oh no, my boyfriend will be home from work in a while. I actually have to start getting dinner ready soon. How much do I owe you?"

"Don't worry about it." Walter couldn't imagine taking her money after what they had done together, even if he was feeling utterly deflated by the news that she had a boyfriend and what she and Walter had done together was not the prelude to a relationship.

"No, I insist!" She handed him a ten-dollar bill. "Is that enough?"

Well, ten dollars was ten dollars. Or, in the Village, two or three used LPs. So he took it. "Thanks."

"Thank you! See you in class."

Walter slowly walked back uptown, not quite believing what had happened. Part of him was exhilarated, part of him was crushed. Instead of dinner with Rachel, he went to the cafeteria, then back to his dorm room. After eating, and after his rollercoaster afternoon, he was feeling contemplative, and nothing would do for that mood but to listen to Keith Jarrett's Köln Concert. He put it on and lay on his bed to listen. Carlton was out, so Walter didn't need to use headphones

It starts so quietly, so tentatively, with a five-note figure in the right hand, a pause as the left hand grumbles, then the right hand repeats itself and continues, gathering courage for a heartfelt statement of yearning. As he listens, the yearning makes him think of Rachel. If not for her boyfriend, would she be the one? The density and intensity of the music builds; Jarrett has set up a groove, and the repetition of some elements along with the addition of further embellishments fills the air with more and more tension until suddenly a wild, effusive flurry of notes flies upward in an ejaculatory release. Then the process starts again, with new melodic and motivic materials.

Just as, Walter thinks, he will find somebody else. This waxing rhapsodic amidst the coming and going of grooves goes on for awhile. Jarrett eventually hits on a particularly insistent vamp on a pedal tone; the pressure builds and builds further until Jarrett unclenches it with a move downward that undams the accumulated tension in a sudden release of orgasmic proportions. That's very nearly the end of the twenty-five minute improvisation, which diminishes quickly to a relaxed glow. It has been a magnificent emotional journey.

The tonearm automatically moves back to its cradle and the turntable stops spinning, but Walter's thoughts continue to churn. If not Rachel, who? Nearly all the women he knows at Columbia/Barnard are in Music Hum or B-C Chorus. He wonders whether his liaison with Janie was noticed by anyone but Martial. Janie not having rejoined presumably means nobody's heard about it from her.

Mara Shapiro, one of the sopranos in the choir, was certainly attractive, but Walter had never had the opportunity to talk to her for a natural reason, nor the courage to just introduce himself. Eleanor Eakins, the tall redhead, also a soprano, seemed to be dating the rehearsal pianist. Okay, going down the list from most attractive didn't seem productive. What women in choir had he had some interaction with who weren't taken? To his surprise, the answer was: none. He had not had a conversation with any current sopranos or altos. He had been too nervous or shy or cautious to take that chance.

With both Janie and Rachel, he had been the passive recipient of attention. He had enjoyed the immediate results, but neither situation had lasted. Well, he wasn't sure what would happen with Rachel, but a relationship was apparently out of the question. Nonetheless, he wasn't sure he had the guts to take the initiative.

Well, if he were to approach a woman in the choir, what would he talk to her about? What was a topic they would both be interested in? Logic said the safest bet would be music. But there would have to be more of a justification. "Hi, would you like to go to a concert with me?" He couldn't imagine being that bold.

But he wrote music. He performed his music. What if he wrote some songs for soprano, and then asked a soprano to sing them? That could work. Not for the band; art songs, just him on piano and her singing. One-on-one collaboration.

He would have to find some poems to set. He knew practically nothing about poetry. He would have to do something about that. One trip to the school bookstore later, he was choosing between Six Centuries of Great Poetry, edited by Robert Penn Warren and Albert Erskine, and Modern Poems: An Introduction to Poetry, edited by Richard Ellmann and Robert O'Clair. He noticed that the former had only British poems, and therefore he opted for Ellmann's volume. He was more inclined to modern poetry anyway; he himself was, after all, aiming to be a modern composer.

Back in his room, he skipped the introductory chapters and dove into the first author collected, Walt Whitman, specifically "Crossing Brooklyn Ferry." Too verbose, too flowery. Next, Emily Dickinson. Certainly not verbose, but somewhat eccentric, and he wasn't at all sure of what she meant. Thomas Hardy was more on his wavelength, and Walter would perhaps look into him more at some time, but his rhythm and tone didn't match Walter's sense of a song lyric. Gerard Manley Hopkins struck him as too pretentious, and self-satisfied as well. Robert Bridges had a whiff of the self-consciously archaic. A. E. Housman was too rhymey. W. B. Yeats seemed uneven in inspiration, but a few of his poems were powerful in a brooding way: "An Irish Airman Foresees His Death," "Easter 1916," "The Second Coming." Nothing made him want to put it to music, though.

Walter skipped ahead to Robert Frost. Some of his poems he had already read in high school. He liked them, sort of; they went down easy. But they were, again, too rhymey, sing-songy. Carl Sandberg's work he had also read and enjoyed before, but none of it asked him to set it to music. Edward Thomas's two inclusions didn't inspire him. Wallace Stevens seemed another wordy sort until he got to "Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird," which was completely different from any poetry he had ever seen before, not that that was saying much given his inexperience. James Stephens had a strong voice, but not for music. Three James Joyce poems made three completely separate impressions; perhaps he was worth investigating further. E. J. Pratt, another too rhymey, and what was with all these guys with two initials?

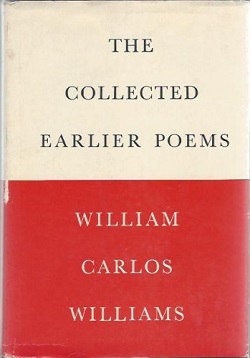

William Carlos Williams. Walter liked Williams's rhythm, which was strong yet irregular, and Williams didn't rhyme, which he also liked. "The Red Wheelbarrow" was the most striking, but he couldn't imagine setting it to music. Still, this guy seemed promising. And Walter was starting to wonder whether the poems selected to represent each author were his best, or instead were trying to cover as many of his styles as possible in the space. D. H. Lawrence's bio was certainly interesting, but none of the poems seemed indecent, though obscenity charges had dogged him. A deliberate omission by the compiler? Anyway, though "The Ship of Death" was compelling, Walter was starting to notice that he was more attracted to the American authors than the British ones.

Ezra Pound was interesting, but the poem Walter liked the most turned out to be a translation of a Chinese poem by Li Po. Walter thought he remembered reading a Pound poem in high school that wasn't here, something about growing old and being indecisive. He'd liked it, and made another mental note to investigate Pound's work further. Two selections each by Hilda Doolittle and Siegfried Sassoon were good but not song material. Robinson Jeffers was powerful, but his topics didn't lend themselves to lyrical songs. Edwin Muir seemed a possibility. Edith Sitwell didn't speak to him. Marianne Moore was fabulous, but not song material. John Crowe Ransom seemed deliberately archaic and Old World.

T.S. Eliot, and it turned out that he wrote the poem Walter had misremembered as being by Pound: "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock." But there had been an Eliot-Pound connection, so he didn't feel too stupid at the mistake. Anyway, the ending of "Prufrock" was his favorite part, so mysterious and doomy. A couple more poems seemed artificial. Then, a long introduction to "The Waste Land," so it must be important. Holy shit, it's fucking brilliant, although without the footnotes he wouldn't know what the hell half of it was about -- yet somehow it had an alluring mood even when its meaning was obscure. He couldn't imagine setting it to music, but wow.

Perhaps because they were in the shadow of "The Waste Land," the next few poets made no impression. Wilfred Owen broke that jinx; writing about World War I, his mood reminded Walter of All Quiet on the Western Front, even though the latter was a novel.

He'd never liked e.e. cummings all that much, and didn't change his mind now. He skimmed through many more, finally brought up short by Randall Jarrell's "The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner," not that it was song material. Then back to skimming. Lawrence Ferlinghetti's one poem seemed promising; somebody else to look into. He should make a list, he thought; in lieu of that, he went to the table of contents and circled the authors who had made an impression.

Then it was back to skimming, until Allen Ginsberg's "Howl" blew his mind. No wonder people at Columbia talked about this man as though he were a god. Not song material, but wow, again. And Walter noticed that its repetitions reminded him of "Crossing Brooklyn Ferry." The voice was more modern, but still, maybe Whitman had been an influence.

Forty pages later, Gary Snyder's "Four Poems for Robin" stood out. Walter flipped back to the table of contents and circled his name. Etheridge Knight, who'd been in prison, had some vivid poems, not song material, but his haiku especially made an impression. Walter remembered haiku from fourth grade and noticed that Knight did not always adhere to the 5-7-5 syllables structure, but also that that didn't make them any less vivid.

Next came a trip to the library, since he didn't want to spend a lot, based on such little evidence, on a bunch of books. There were big collections of Stevens and Williams, which he took out. He looked up Li Po and found more modern translations by Kenneth Rexroth in Chinese anthologies he'd both edited and translated. Walter couldn't find any Gary Snyder books, but he felt like he had enough to keep him busy, as his father liked to say.

Next came a trip to the library, since he didn't want to spend a lot, based on such little evidence, on a bunch of books. There were big collections of Stevens and Williams, which he took out. He looked up Li Po and found more modern translations by Kenneth Rexroth in Chinese anthologies he'd both edited and translated. Walter couldn't find any Gary Snyder books, but he felt like he had enough to keep him busy, as his father liked to say.

Back at his room, Carlton was studying at his desk. Walter put his headphones on, picked up where he had left off with Jarrett's Köln Concert, and dove into The Collected Earlier Poems of William Carlos Williams. Pretty soon he was sure he'd be turning some of them into songs: "To a Solitary Disciple," "To a Poor Old Woman," "This Is Just to Say" (he imagined combining those two, since they both hinged on plums), maybe "At the Ballgame," the short version of "The Locust Tree in Flower." He made a list, then went to sleep.

Roman AkLeff says of Music and Sex, his third attempt at a novel: "Lots of the events depicted in this book happened, to varying degrees. Some should have happened but didn't until now. Though it's mostly set in the 20th century, Music and Sex aspires to be a Bildungsroman for 21st century sensibilities, in that the main character doesn't finish coming of age until he is several decades into adulthood."