How to Change the World

How to Change the World How the Light Gets In is a wonderfully eclectic confection of philosophy, art, film, and music. An annual event spread over eleven days in the small market town of Hay on Wye, it is stimulating. diverse, and largely at the mercy of the elements. A strangely appealing mixture of tents and marquees spread, in a seemingly random fashion, over a site that has a myriad of pathways and stairs. You get the feeling of being transported back centuries to a rustic fair. Today the sun is shining, a direct flip of the downpour of yesterday, and there's an air of celebration added by the bars, and the constant variety of singers and entertainers who are happy to perform to the few or many who decide to stop and listen.

Although he wasn't the support act for the event I had in mind, being merely a stairwell's wander from the main hall, and whilst waiting I caught an all-too-brief set by a singer songwriter called Rhys Lonnen, who performed a handful of well crafted, confessional ballads, revealing on a maiden listen, an admirable sense of song-craft, aided and abetted by his excellent, understated guitar playing. He even covered "These Days" by Jackson Browne, blowing the Gothic moodiness of Nico's beautiful, haunted version into the sunshine outside, and revealing the song in all its true freshness, despite it being almost half a century old. Lonnen has his debut release out soon, so to catch something fresh whilst waiting was an unanticipated pleasure and surprise.

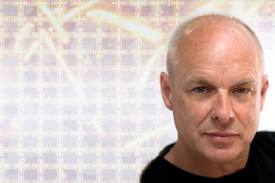

The Globe Hall must once have been a chapel. It has a pulpit on the right, which today is filled with cardboard boxes and some unwanted electronic equipment. This vision could stand as an installation art piece; in different circumstances it would. It could also be a strangely abstracted portrait of one of the panel. Forty years since he sprang into being as the prancing effete who added electronic strangeness to the original art-rock merchants Roxy Music, Brian Eno has been at the left of center, creative bacteria of many artistic cultures since, from Bowie to Talking Heads and U2 to Coldplay. He has long since ceased to be the darkly plumed bird of paradise, that wonderfully mismatched counterpoint to Mr. Ferry's gothic peacock in full preen. Today beneath long windows draped in blue cloth, he is understated in a black leather jacket.

The event is a discussion based around the idea that we might require a new Renaissance. For someone who has created a myriad of ambient soundscapes, there is nothing vague about his thinking. He states that capitalism "ships off external costs into the future" with its devouring of fossil fuels and creation of carbon dioxide. A more pragmatic approach could be employed and still be capitalist, the idea of a free market with a conscience, so it can be phased in as an opportunity, and not a patch-up job. Eno believes that "good ideas become acceptable to politicians when they realize that enough people want change," citing the revulsion against the trade of slavery, which was abolished at the height of its economic success. His remark that there are "very few idealistic politicians who'll risk their jobs" rings sadly true.

As the discussion evolves, he maintains that laws, both new and improvements upon present ones, are a means towards prevention, containment, and control. Constrained capitalism already exists, since we no longer have child labor, and we do not consider that a restriction, more a moral imperative, where a sense of honor and shame goes hand in hand. Hardly surprisingly, he is interested in the way in which popular culture can assist the process, stating that nearly all popular culture starts at the bottom, citing the influence of songs of plantation workers and immigrants, and how these work their way to the top and are repackaged, after which the process begins once again. Of the wider political arena, he maintains that "a few more scientists and engineers would create a more literate government" and not one driven by the "toxic fundamentalist capitalism of the U.K. and America" and that those in office should "make it a de facto rule that governments should fund their own critics." Things are run in Britain in a ridiculous, reverse order. Most is spent on weapons, then banking, followed by culture and education. He emphatically insists that this utterly ridiculous situation needs redressing and cites aspects of European capitalism as being less obsessed with a quick return, more patient, and prepared to wait, as indeed things once were here.

At the end, as is the case with discussions of this nature, there is much to contemplate, but the world has not been saved, and the new Renaissance is still under consideration, probably in cyberspace, and this occasional congregation disperses in a scratching of mismatched chairs. It is a testament to Eno's convictions, long held and never diluted or laid aside because of success, that he still is bothered and bothering to contribute to an on-going debate. As James Thornton slips into the daylight and wends his way towards the small pavilion to sign his book, Eno follows, and stands by the table, on a carpet of wood shavings, sipping a glass of wine. A faintly surreal vision on a Summer's day in Wales, but one still warmed by these hopes for another green world.