December is a month that increasingly sees few releases of new albums, so the closer this list gets to the present day, the fewer albums of importance there are to discuss, and most of those are hip-hop albums.

1967

Traffic: Mr. Fantasy AKA Heaven Is in Your Mind (Island)

Shortly after Steve Winwood quit the Spencer Davis Group (of which he was the lead singer and organist), he formed Traffic with some guys he'd jammed with at a club in Birmingham: guitarist/vocalist Dave Mason, saxophonist/flutist Chris Wood, and drummer/lyricist Jim Capaldi. After a couple of hit singles, they convened at a country cottage and put together the debut album by Traffic, titled Mr. Fantasy in their native country. By the time it was released, Mason had already quit.

The English and American editions were rather different. Not only did the U.S. LP (on United Artists) have a different title (Heaven Is in Your Mind) and cover art (minus Mason), and a dozen tracks instead of twelve, it left off two of the English edition's songs, "Hope I Never Find Me There" and "Utterly Simple," both by Mason, and added two early singles, "Paper Sun" and "Hole in My Shoe," plus "Smiling Phases" and the brief "We're a Fade, You Missed This," which is a slight return of the end of "Paper Sun." The track order was also vastly different, and the mixes varied as well.

The song "Dear Mr. Fantasy," for all its popularity, was not a single. Winwood's world-weariness and cynicism about rock stardom shines through, but that doesn't keep him from enjoying a long guitar solo in the spotlight. The iconic harmonica bursts come from Mason, who also plays bass on this track; Chris Wood plays the organ part.

Though Winwood came out of a beat/R&B background -- he's got one of the most soulful vocal styles in English rock -- Traffic at this point was mostly a psychedelic band, with Mason in particular strongly focusing on that style, which was no commercial liability in England in 1967. Winwood was more interested in jamming, but that's not exactly inimical to psychedelia. However, British psychedelia sometimes drew on different sources than American psych, a prime example being ironic use of old-time dancehall (unrelated to the later reggae style), as heard here on "Berkshire Poppies." There's also more whimsy, such as the way "House for Everyone" winds down at the end like a music box. It also tended to be more literal in its incorporation of Indian music, with actual sitar and table, as on "Utterly Simple" and the aforementioned singles, instead of rock approximations. Somewhat related to psychedelia is how the dark side of drugs -- well, one dark side – appears on the sinister "Dealer," which warns what a dangerous character the title figure can be if he's crossed.

By the time Mason returned in 1968 for half of the band's eponymous sophomore effort, Winwood had tipped the balance towards his R&B influences, and the quartet was never again as psychedelic as it had been at its birth.

Jimi Hendrix Experience: Axis: Bold as Love (the epitome of non-San Francisco psychedelia)

Rolling Stones: Their Satanic Majesties Request (their psychedelic album is better than its reputation, and because most of it is less frequently heard, sounds fresher than most of their Sixties catalog)

Beach Boys: Wild Honey (their last mono album)

The Who: Sell Out (one of the funniest music albums by a major classic-rock group, thanks to its many fake commercials)

Bob Dylan: John Wesley Harding (his post-motorcycle accident comeback has an austere sound and a philosophical outlook full of Biblical allusions)

Leonard Cohen: Songs of Leonard Cohen (Cohen’s debut sold slowly -- it didn't go gold until 1989 -- but his poetic songwriting was much admirer by his peers, and many of the songs here have been covered multiple times)

Dusty Springfield: The Look of Love (the Bacharach/David-penned title track is Dusty at her most sultry, and that's saying something)

Paul Butterfield Blues Band: The Resurrection of Pigboy Crabshaw (proof that there was life after Michael Bloomfield's guitar tenure; he was replaced by Elvin Bishop [the album title's a reference to the latter], which moved the band from the blues and psychedelia of its previous release to more of a soul sound, complete with a horn section featuring alto saxophonist David Sanborn)

1972

Deep Purple: Made in Japan (Warner Bros.)

Deep Purple: Made in Japan (Warner Bros.)

This British band started out as heavy psychedelic pop, became progressive rock, underwent a few personnel changes, and then became one of the most important early metal bands with its classic lineup consisted of singer Ian Gillan, guitarist Richie Blackmore, organist Jon Lord, bassist Roger Glover, and drummer Ian Paice. After releasing their most popular album, Machine Head, earlier in the year, the band headed out on tour, and was captured on tape in Japan in August, quickly resulting in this epic double LP that is reputedly Lord's favorite album by the band. Certainly it's the one where he and Blackmore get to stretch out the most on their solos. "Space Trucking" expands to just shy of 20 minutes, and there were just seven songs on the original release's four sides (on CD, three tracks have been added).

It's appropriate that "Space Truckin'" finds Lord quoting Gustav Holst's The Planets (specifically the "Jupiter" movement). Listen to "Smoke on the Water" and a probable influence on Gillan leaps to mind: The Crazy World of Arthur Brown, especially, of course, "Fire." Gillan's style would prove massively influential on heavy metal singers; his powerful screech echoes down the decades, heard in such followers as Axl Rose. By the end of the following year, Gillan and Glover had left the band, but here -- missing just one of this incarnation's classic tracks, "My Woman from Tokyo," which they wrote about the trip on which this album was recorded -- they were at their peak.

Marvin Gaye: Trouble Man (yeah, it's a soundtrack, but the soundtracky bits rise above mere functionality, and the title track is a masterpiece)

Neil Diamond: Hot August Night (another live double from August ’72, complete with orchestra)

Gentle Giant: Octopus (prog-rock's most determinedly complex band hits its stride)

1977

Brian Eno: Before and After Science (Editions EG)

Brian Eno: Before and After Science (Editions EG)

A turning point in Eno’s career. In fact, the turning point can be felt on turning over the LP from its A to B side. The A side is full of the quirky prog-pop and witty lyrics that had characterized Eno's previous LPs. Except for the brief, moody instrumental "Energy Fools the Magician," the A side is all uptempo. The funky "No One Receiving" seems like an evolution of Bowie's "Golden Years"; "Kurt's Rejoinder" includes samples of avant-gardist Kurt Schwitters's abstract vocal sounds poem "Ursonate"; "King's Lead Hat" (the title is an anagram of Talking Heads) verges on nonsense lyrics but includes a fine, angular Robert Fripp guitar solo. Eno is joined by a variety of guests, mostly guitarists, drummers, and bassists, including Fred Frith, Phil Manzanera, Phil Collins, Percy Jones, Paul Rudolph, Andy Fraser (Free), Dave Mattucks (Fairport Convention), and Can's Jaki Liebezeit.

Side B is drastically different. Oh, "Here He Comes," the first track, is a gentle pop song, much less energetic than anything on Side A but still a familiar sort of piece similar to some tracks on Another Green World. After that, though, Eno combines simple song structures with the stripped-down textures of the ambient music he'd begun working on two years earlier. It sounded like nothing else happening in 1977, or maybe ever. "By This River" reunites him with Achim Roedelius and Mobi Moebius of Cluster, who co-wrote the song. The other three songs are ruminative and wistful, creating a uniquely intimate sound world. Aside from a co-led project with John Cale, they would be Eno's last songs with vocals and lyrics until 15 years later (Nerve Net).

Aerosmith: Draw the Line (bounces from boogie riffing to nearly prog to blues without ever reminding us of Aerosmith at its earlier best)

Al Green: Belle Album (Green’s last truly great album, an intimate, underrated classic of late-‘70s soul)

Jackson Browne: Running on Empty (a live album, recorded on the road -- sometimes literally [on the bus, and once on the side of the highway], sometimes in hotel rooms or backstage, and of course during actual concerts)

Roberta Flack: Blue Light in the Basement (the big hit was “The Closer I Get to You,” a duet with Donny Hathaway; connoisseurs of underground soul will note the many tracks credited to Gene McDaniels)

Joni Mitchell: Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter (Laurel Canyon meets jazz fusion, with Glenn Frey and J.D. Souther alongside Wayne Shorter and Larry Carlton on what seems like a deliberately uncommercial double LP)

Suicide: Suicide (harsh, brutal, and vastly influential; practically uncategorizable except retrospectively/anachronistically)

Wire: Pink Flag (the debut of one of the top five British punk bands, though after this they quickly moved on to post-punk)

1982

Neil Young: Trans (Geffen)

Neil Young: Trans (Geffen)

The most notoriously polarizing album of Young’s career, and the first shot fired in the battle for creative control between Young and label owner David Geffen, came about because Geffen rejected an earlier submission that was all “normal.” Young kept some of that album and mixed in six tracks from an older, unreleased set of recordings, stripping out backing band Crazy Horse’s instrumental tracks and replacing them with synthesizer parts, then electronically distorting his voice (using a Vocoder), which for him symbolized how his son Ben, severely afflicted with cerebral palsy, heard the world. Young had heard Kraftwerk, and apparently found them interesting, but nobody would confuse Trans with the smooth textures and unemotive sounds of their Autobahn.

Geffen eventually (unsuccessfully) sued Young for deliberately making stylistically un-Young-like albums, with Trans being a prime example. It has never been issued on CD in the U.S., though the German-issued CD became a popular import among Neil diehards.

The Jam: Dig the New Breed (swan song of live tracks from through their career, issued after they’d broken up)

Bob Seger: The Distance (I bet you didn’t know that Seger’s highest-charting single is “Shame on the Moon,” off this album)

1987

Dinosaur Jr.: You’re Living All over Me (SST)

Dinosaur Jr.: You’re Living All over Me (SST)

The second LP by this Amherst- based trio was an advance on their debut. The songwriting was a little better; the sound was a lot better; the style, although still all over the place with its mix of hardcore, college rock (as it was known then), Stooges, Birthday Party, and Neil Young worship, had cohered a bit; the band, though still loose, had tautened enough to make more of a focused sonic impact; and -- perhaps most of all -- being on SST displayed an imprimatur of quality that was respected throughout the underground scene. Also, one of the band's fans, Sonic Youth’s Lee Ranaldo, joins on opening track “Little Fury Things,” adding backing vocals and an implicit endorsement. Sonic Youth was very guitar-centric, so bringing Dinosaur Jr.'s guitar-heavy sound to the attention of SY fans (not just through that cameo, but as opening band on tour) spread their reputation quickly.

1992

Dr. Dre: The Chronic (Death Row/Interscope/Priority)

Dr. Dre: The Chronic (Death Row/Interscope/Priority)

Dre’s first solo album after quitting N.W.A. was ultimately more influential on hip-hop production -- and, nowadays, pop music production -- than any of his old group’s albums. Drawing on the sound of Parliament records, his production style (dubbed G Funk, which even looked back to the P-Funk designation of the combined Parliament and Funkadelic band) featured slow beats, low and mellow bass lines, and high synthesizer melodies. Oh, and the rapping of Snoop Dogg, whose popularity was greatly enhanced by his many guest appearances (11 out of 16 tracks) on this album, which preceded his debut LP.

Nirvana: Incesticide (a compilation of non-album tracks and previously unreleased material; highlights include the covers of one Devo song and two by the Vaselines)

1997

Eminem: The Slim Shady EP (Web Entertainment)

Eminem: The Slim Shady EP (Web Entertainment)

On the strength of this release, Dr. Dre agreed to sign and produce Eminem. The beats are nothing special, and often subpar, but Eminem's flow had greatly improved since his earlier release Infinite, and he had developed his own style, which was often as much storytelling as rhyming. Grittier, darker, angrier, and more personal than his earlier album, The Slim Shady EP also introduced his infamous alter ego of the title. He got much better than this on the strength of Dre's production, but his roots are strong here.

2002

Nas: God's Son (Columbia)

Nas: God's Son (Columbia)

Yeah, Nas has a pretty high opinion of himself, as the title shows. But even if his rival Jay-Z has vastly surpassed him commercially, Nas with his old-school production and beats and his single-minded focus on crafting an aggressive flow may be more of an artist. After a bit of a lull, he'd started a comeback the previous year that peaked with this masterful album.

2007

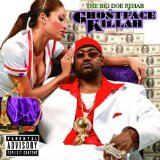

Ghostface Killah: The Big Doe Rehab (Def Jam)

Ghostface Killah: The Big Doe Rehab (Def Jam)

The best rapper in Wu-Tang Clan was not shy about voicing his annoyance when RZA scheduled a Wu-Tang album for release on the same day as this album. RZA pushed the Wu release back a week in deference, and Ghostface's revenge was that this -- if not as great as his release the previous year, Fishscale -- was a better album. Oh, some of the beats were kinda tepid, but it was more coherent (though when it comes to Wu-Tang albums, that's not setting the bar too high) and of course the rapping was vastly superior and way more fun.

B'z: Action (16th album by this Japanese band hit #1 in their home country; it even got some international attention after the song "Friction" was used in the video game Burnout Dominator)

Wu-Tang Clan: 8 Diagrams (their first album together since the death of Ol' Dirty Bastard)