The Art of Rube Goldberg

Queens Museum

Flushing Meadows–Corona Park, New York

Rube Goldberg defied the odds. He was a highly paid and award-winning artist at a time most such practitioners were living hand to mouth. He collapsed the cavernous divide between illustrative or commercial art and fine art with a popular, albeit wildly witty vision. He bridged the gap between engineering and fine art in a way that was both compelling and entertaining to his audience, by inventing compellingly impractical machines to complete mundane tasks. And he eventually became a spokesperson for a number of products such as Luck Strike Cigarettes (Goldberg only smoked cigars) and Old Angus scotch whiskey.

Goldberg created some 50,000 works, mostly on paper that were drawn or painted with black ink. You don’t often hear of such a staggering output of work. Myself, I can only think of Picasso, who too amassed such a number, which included paintings, sculptures, collages, prints, ceramics and textiles. And it is also important to note that their eras overlapped: Picasso 1881-1973, Goldberg 1883-1970, while both were the greatest, most recognizable figures of their related fields.

Picasso's legacy can be found in every important museum in the world, or in any volume of Modern Art. Goldberg’s legacy lives largely in the memories and minds of artists, engineers and inventors, people who see the beauty in belaboring a simple task creatively, by employing endless ingenuity. In fact, Rube Goldberg is listed as an adjective in Miriam-Webster's Dictionary, and there is something called the Rube Goldberg Machine Contest, a national competition that occurs every year. In it, six finalists from various colleges and universities compete as they conceive of, design and build machines that turn an everyday task into dozens of otherwise frivolous actions that, when occurring in a crazy continuum of wiggles, waves and whirligigs, completes a uncomplicated task that would normally take a person one or two trouble-free movements or moments to achieve.

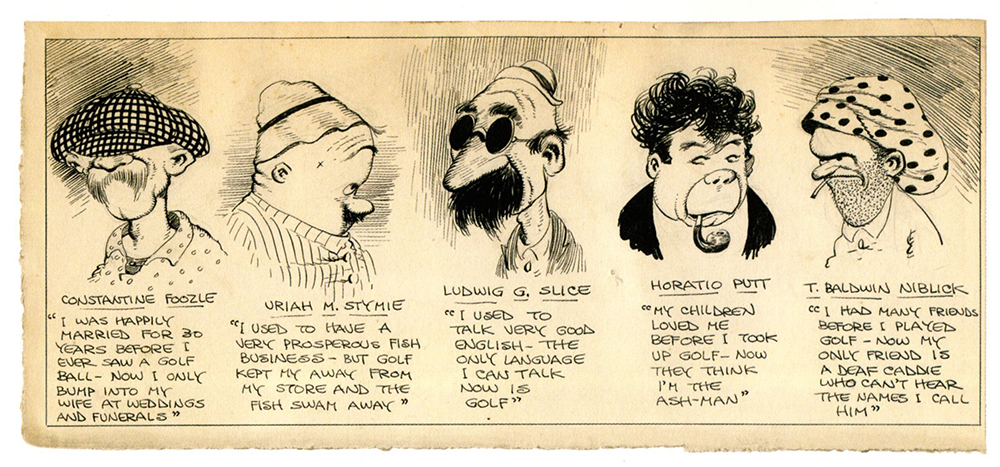

My renewed enthusiasm in Rube Goldberg's legacy all comes from a recent talk and exhibition I attended at the Queens Museum, which was aptly titled The Art of Rube Goldberg. Conceived of by artist Creighton Michael, curated by the Senior Curator of the Aspen Art Museum, Max Weintraub, and toured by International Arts & Artists, The Art of Rube Goldberg stands as a glowing reminder of just how influential Goldberg was in his day. Like some, I am most familiar with his mesmerizing machines, and was pleased to learn of and see more of his voluminous cartoons and strips that had a distinctive, modern (for its time) and very humorous look at social behavior, human and personified animal mannerisms and all the trials and tendencies we project in terms of class, gender, religion and most importantly relaxation.

The talk consisted of two presentations. The first was by Jennifer George (Fashion Designer and the artist’s granddaughter, and author of the book, The Art of Rube Goldberg), and Charles Kochman (editorial director of Abrams ComicArts and editor of the book). Both highlighted Goldberg’s education as an engineer, his life as a father and grandfather, and his continued creative influences, which are far-reaching, sometimes anecdotal, and always cross-cultural. The second overview of Goldberg was given by Creighton Michael, with his thoughts of Goldberg's relationship to key art historical figures, pointing to Da Vinci's caricatures that focused on harsh, distorted facial features of everyday people; and Peter Bruegel the Elder’s powerful storytelling ability.

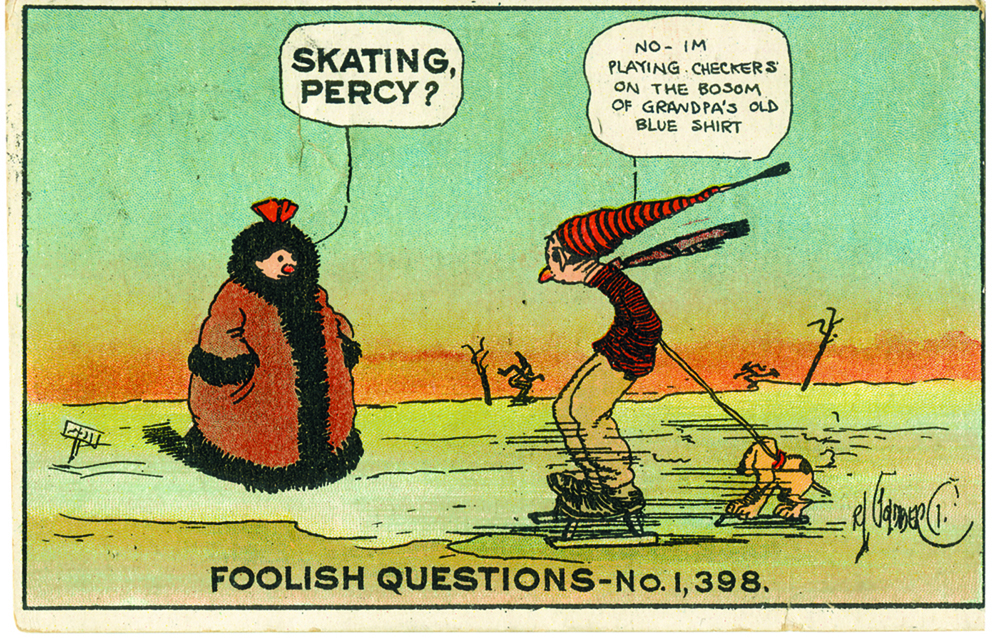

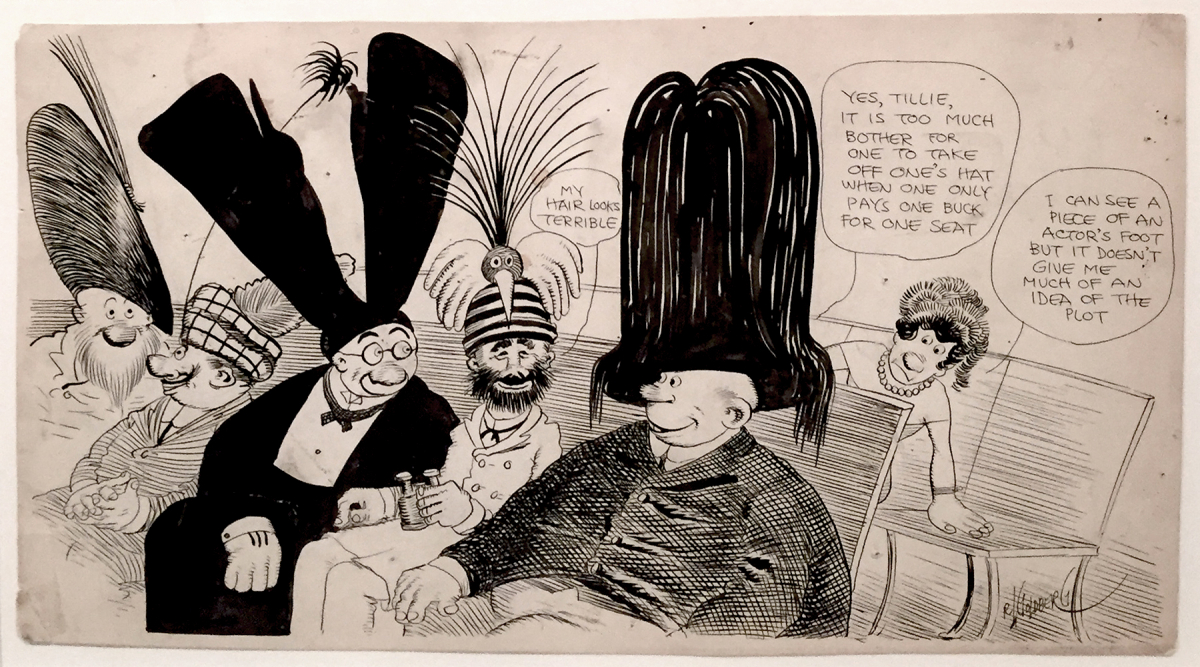

Looking forward from Goldberg's influences, I noticed one link between he and Robert Crumb. Not so much in the content, of course, but more so in the absurd levels of social interactions. Crumb does credit Goldberg, among many others of those early cartoonists as influences, and I believe you can see it most easily in works from the incredibly popular, and always stinging and zinging retorts in his Foolish Questions series (1909-1934), or in the wildly reactive fantastical fashion fiasco in Men in Hats at Theater (1926).

Then there are the many thousands of cartoons Goldberg created that truly defined an awkward era, revealing a magical mindset that only he could portray. In addition, Goldberg was awarded a Pulitzer in 1948 for his political cartoons, some of which are in the exhibition. The most powerful and timeless work is Jews and Arabs (1947), which depicts two lone figures crossing an endless dessert in parallel paths that one must assume have been forged by generation after generation. The irony here is they are headed in the same direction, unaware of each other's presence despite their relatively close proximity. Profoundly, Goldberg is pointing out both the differences and similarities of the two peoples traveling roads that unfortunately, may never meet.

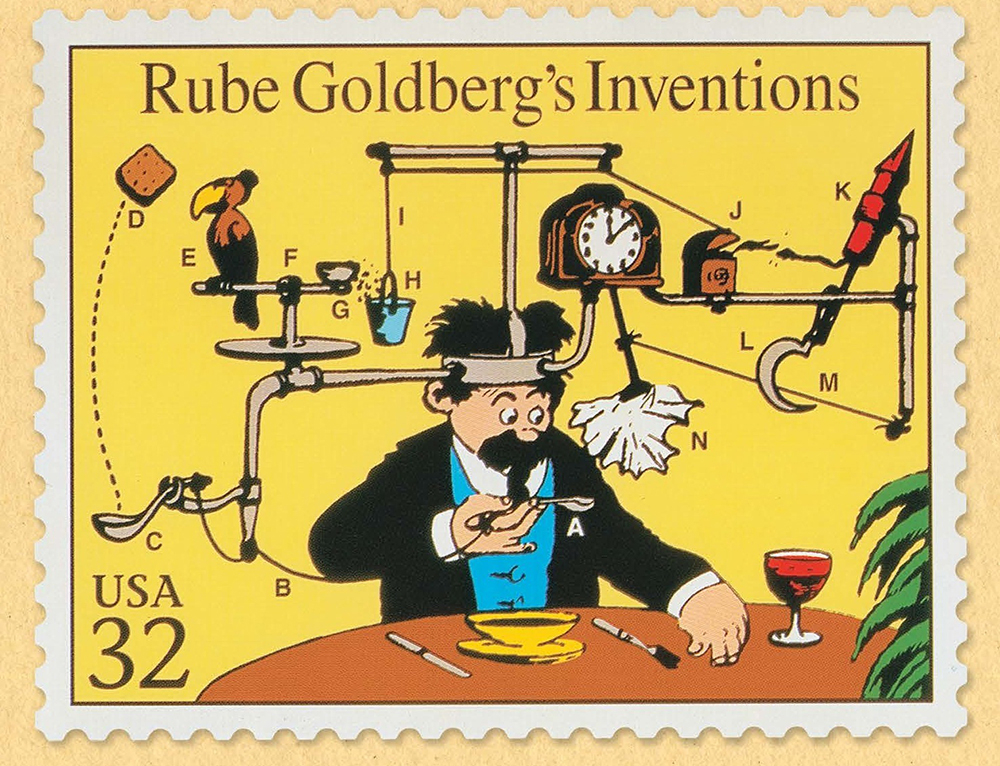

Goldberg also had a postage stamp created in his honor; a color version of one of his most familiar works, Professor Butts and His Self-Operating Napkin (1931). The stamp was issued in 1995, while the original work can be credited in influencing Charlie Chaplin’s great film Modern Times (1936), which features a self-operating napkin machine.

And those machines, oh those machines. They were, and still are transfixing to me, especially the ones that are considered "wearable". For instance, Professor Invention Drawing (An Idea to Keep you from Forgetting Your Wife's Letter) (1930) shows a man who is just about to pass a letter box, as a device he is wearing strapped to his waist goes through over a dozen key points or movements to remind him to mail a letter his wife gave him. What really rings true here is the nod to human nature, how we tend to daydream. Getting lost in one's thoughts, how one forgets what they set out to do as they move from place to place with intended goals, big and small is something anyone can relate to.

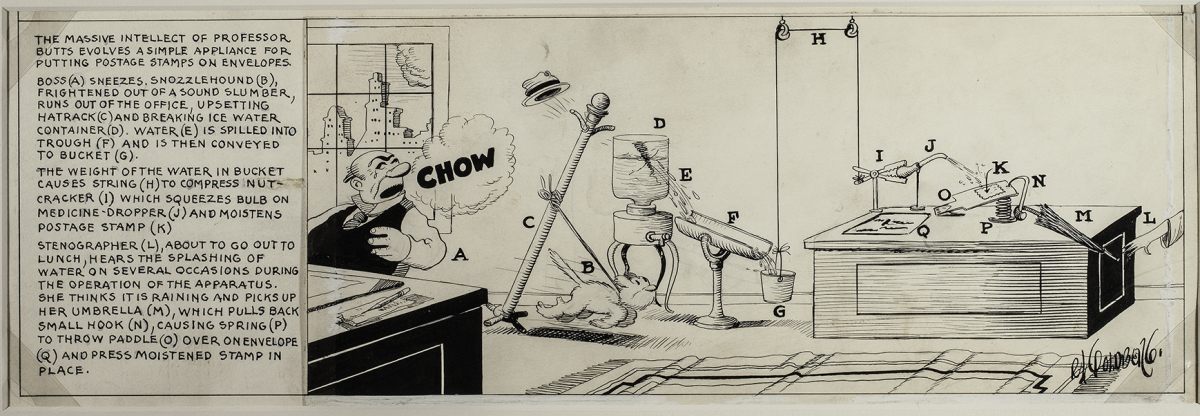

Goldberg continues to turn minutia into magic with Professor Butts Invention Drawing (Postage Stamps) (1929) that, using various sounds in a mix of progressively bizarre mechanisms, places a moistened stamp on a letter. In this instance, as Creighton Michael pointed out in his presentation, Goldberg utilizes diagonal forces to enhance the movements, while the contrasting dark sides of the two desks helps to both move the eye and create depth.

The Art of Rube Goldberg at the Queens Museum, which also includes film shorts produced by Goldberg, videos of the influences of Goldberg, games, functional objects, books, strips, play money, advertisements, illustrated articles, and archival film clips, and photographs runs through February 9th, 2020. Be sure to see it, and the other wonderful exhibitions the museum offers.