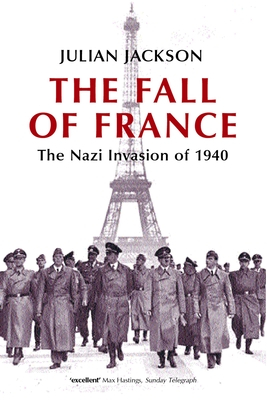

The Fall of France: The Nazi Invasion of 1940

by Julian Jackson (Oxford University Press)

History tends to be written by the winners. How interesting and how poignant it is, then, to read a history of loss, specifically the way that France -- glorious, democratic, politically and artistically advanced France -- folded in three weeks' time to the Nazis during the first half of the first year of World War II. Julian Jackson's The Fall of France, while not written with the style of a Nabokov or the wit of a Wodehouse, has the power to shake you to the pit of your stomach, and to make you ask questions that reverberate to the bottom of your soul. And keep turning the pages in a blur all the while.

It's not a new book, it's a few years old. But I don't think it's merely the ravings of a dyspeptic, misanthropic mind to say that this brief history packs more emotional punch than almost any novel or memoir I've ever read. And, even though it recounts a historical event that took place a couple of generations ago, it's as pressing and urgent as anything in today's papers (or webpages.) And that's not even beginning to talk about the characters. If memoirs of abuse are all the rage, Jackson's The Fall of France could be the memoir of our modern world's abusive childhood. How Churchill arrived in France just as the battle was being begun and how he asked about the French reserves and how he was told, "Aucune" -- None. How the wisest, most lauded military myths of Napoleon crumbled, with generals crying and the free world being defended by a handful of long in the tooth, ill-equipped second-tier reservists. How these men, who even if they were first tier, couldn't have help but been shattered by the amplified whirring of the diving Stuka bombers. How the best laid plans evaporated and accidents and mistakes ruled the day. You don't have to be a military history buff to get the sense of utter confusion that reigned as the Maginot line was circumvented, the Ardennes crossed, the Meuse forded, the village of Sedan broken. This is life lived large -- where heroism and stupidity snuggled up next to one another.

Jackson boldly tears away the piety that caused France and French historians to obliterate 1940 from their calendars, and begins to tear away the cloth and examine the truth of the war verses the myth; the toxic anti-Semitism that doomed the French coalition that could have held off Hitler, the deep seeded anti-French and pro-Hitler feelings that guided England, and that, if not clouded by the hindsight of victory, could have painted Churchill and his cronies as much of dimwits and cowards as the French regime. This is, in fact, the first warning shot of a kind of brutally honest revisionist history on the war we will be seeing more of as the final surviving veterans of the war pass away. It proves that truth is much stranger than fiction. Jackson quotes from the diaries of French foot soldier Jean Paul Sartre. He dips into diaries of scholar soldiers and citizen soldiers, Frenchmen who, instead of cowardice, show unbelievable bravery: one Marc Bloch, who had no sooner marshaled a ferry of soldiers to safety in the midst of the Dunkirk retreat than he turned around and sent himself right back into the fray, into the middle of Nazi-occupied France.

In the midst of this swirling narrative emerges a nefarious woman, the mistress of the final free French president Reynaud, Helene de Portes who is making policy, snooping on meetings, and making mischief, and who was saved universal ignominy by her accident of dying in car crash at the end of 1940.

The story is all the more fascinating because it is true. Or at least as close to truth as a recounting of events that happened can be. Jackson comes to no clear conclusion, which is the most unsettling part of all. The best he can do is reclaim some repudiations, call into question others, and posit that the decisive action of France's sudden fall propelled the World War from a regional conflict to a global one, a battle whose reverberations are still being felt today. His lesson is that there is no lesson. And that is the most chilling ramification of this tome for our time, or any time.