The Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center's Permanent Collection

Vassar College, NY

My original intent was to review one of the four new exhibitions at The Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, but as museum's often go, I am more drawn to the offerings of their permanent collection. This is not to say the four ancillary curated exhibitions are not wonderful, they are. I just need to focus my comments as there is so much here to see, and no matter when you might visit this museum, you will have a very fulfilling experience, especially if you engage one of the extremely knowledgable guards who enjoy sharing compelling facts about the art. Just to give you an idea of what you might see here, I will focus on a few highlights from the museum's Modern Era collection. Francis Bacon's Study for Portrait IV (1953) is one of five studies Bacon painted for his famous rendition of Diego Velazquez's Portrait of Pope Innocent X (1650). Here, one might note that besides the missing scream, Bacon has experimented a bit wore with the flow of the linear background as it corrals the subject, who in this version, has the lower half of Pope Innocent X's face covered with his hand, perhaps indicating vulnerability, feigned innocence or shame.

Next is La semaine des quatre jeudis (The Week of Four Thursdays) by Balthus. Painted in 1949, this work has the artist's familiar dramatic narrative enhanced by passion inducing romantic lighting. Balthus's propensity to suggest 'subject-awareness' of the observer by the main subject is abundantly clear, as the largely delicate modulating earth tones propels the narrative, which has endless ways to precede. On the other hand, Louise Nevelson's Dawn's Wedding Feast Columns (1959) feature two totemic forms that have an overwhelming spiritual presence, like beacons of enlightenment, alluding to a multitude of current day cultural leanings and the suggestion of future aesthetics.

Arshile Gorky's angst riddled The Horns of the Landscape (1944) is a stunning example of his later work. Intensely painted, this painting riffs off of arching black lines, perhaps drawn with vine charcoal, inspired by the wispy movements of his ambient landscape. A master of experimental technique, Gorky turns it all into a rather distopic vision of intermingling forms dripping under invasive splashes of turpentine.This 'melting' aspect of the paint poignantly warns us of the coming age of atomic bombs and their horrific aftermath. Elaine De Kooning brings back some semblance of hope, albeit with as much disorderly order as Gorky's technique, in Man in a Whirl (1957). The drips here, which spread along the top of the composition, are less imposing and perhaps, add a bit of whimsy, while the rest of the painted surface is more solid with thick weighty stokes of paint that create a greater depth of field. Both works are very much about action, movement and atmosphere that project imposing thought processes.

The canvas by Joan Miró, Painting (Birds, Personages, and Blue Star) (1950), and Karel Appel’s Child and Beast II (1951) add more than a tinge of joy to the museum experience. Miro’s lyrical design, inhabited by numerous weightless symbols, glides easily into the viewer’s subconscious, while Appel’s CoBrA tendencies, which often mean the study of the art of children, comes through with flying flamboyant colors. Alexander Calder’s fun, table top Mobile (1934) looks a little like a very distilled abstraction of a head of a bull at certain angles. Nearby, Au printemps (1955) by Hans Hofmann certainly has very clear indications of springtime’s rebirth with its dabs of color (flowers), as the artist incorporates his famous theory of push and pull, and his career long tendency for discovering endless, refreshing ways to apply paint.

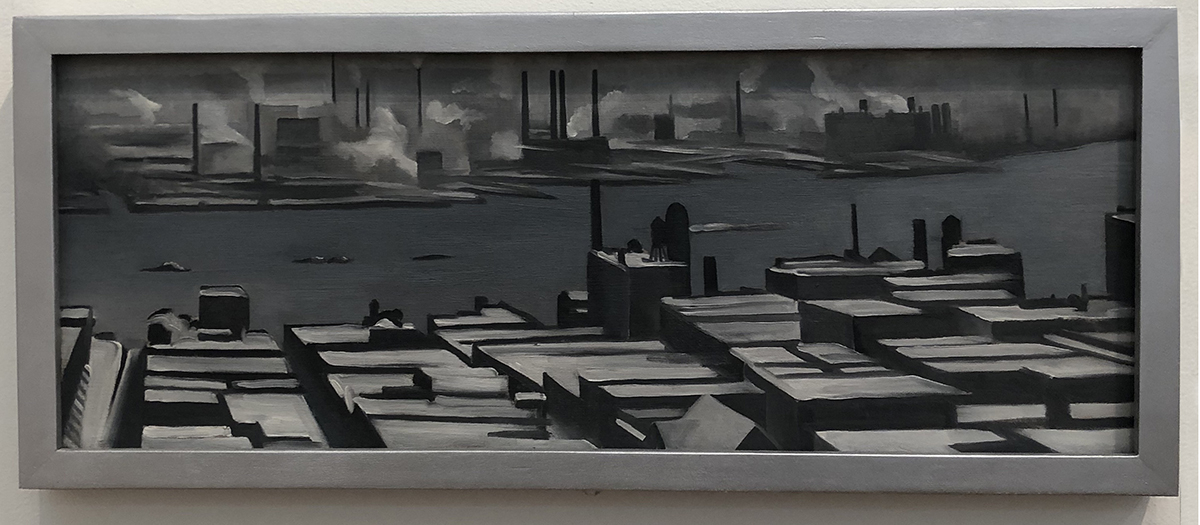

The weightiness returns with Broome County from the Black Diamond (1931-32) by Arthur Garfield Dove, where a massive, giant clam-shaped storm clouds hug the mountaintops. The lure here is the mix of abstraction and representation, and the grounding color that makes this rather small painting immensely powerful. Marsden Hartley's Indian Composition (1914) has what makes this artist's paintings so compelling; that knack for experimental composition and an ability to unravel the challenges of centralized structural balance. Georgia O'Keeffe's East River, No. 3 (1926) is the view from above the rooftops of the east side of Manhattan, looking even farther east at the factories across the river in Queens. A rare glimpse of her ability to capture the complexity of a time in a burgeoning city in stark detail and little color, as opposed to her more familiar colorful, closeup renditions of flowers. In this instance, you can almost feel the artist's aching, her wanting for space, nature, and fresh air.

Alexej von Jawlensky's Woman in a Hat (1910), with its Fauvist tinge, is a wonderful example of the Expressionist movement, and one of the best I've seen by this artist's type. Then there is one of the more peaceful examples of a painting by Edvard Munch, The Seine at St. Cloud (1890), which at first glance looks more like a James Abbott McNeill Whistler than a Munch. However, when peering in a little closer at the painted surface, it is clear by the boldness of the expressive brush strokes, especially at the top of the tree, and the emphasis of the reflections of light on the water, that this work comes from the hand of Munch.

For more information regarding hours and current exhibitions please visit https://www.vassar.edu/fllac/exhibitions/