One night recently I couldn't sleep, so I turned on The Irishman. I told myself I'd watch it for a few minutes. Just till I get drowsy, I thought.

I'd seen Martin Scorsese's film in a theater when it came out in 2019. But now that all the hubbub about DeNiro's digital de-aging and the Netflix's Oscar gambit had died down, I decided a fresh look was in order. Where did it fit in Scorsese's pantheon? I could call up moments: Frank Sheehan in the old folks' home; the assassination of Joey Gallo; Anna Paquin's haunting presence; Frank's stammering phone call to Hoffa's widow just after he, Frank, had just killed the man. All my memories of The Irishman were all fond. What better time to rewatch it than in the wee small hours?

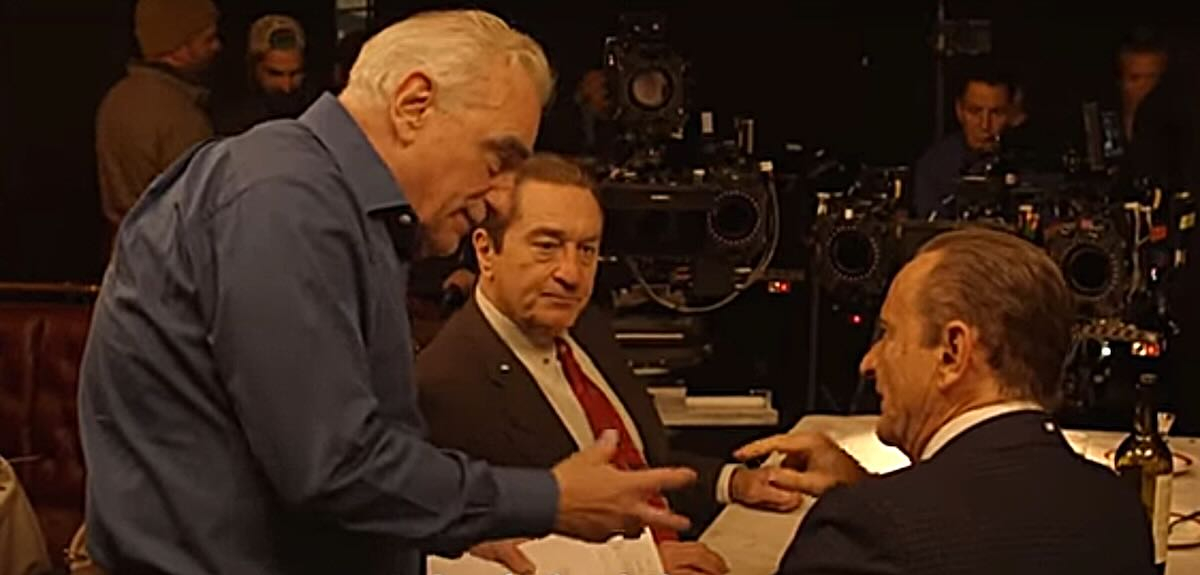

As a show of craft the film is stunning, the work of a cinema master. As a tableau of characters and events, it is as sweeping an epic as has ever been shown on any screen, big or small. I couldn't watch it without thinking of Goodfellas, Casino, The Departed—Scorsese has remained on point, seeing America's epochs through the lens of the gangster picture. The Irishman is as propulsive as the others but more contemplative. Its violence is low key and mostly seen from a distance.

Watching it late at night, I fell into a deeper appreciation. Martin Scorsese, I realized, is one of the few filmmakers who has been able to complete his oeuvre in a genre for which he is best known. We can say that of Hitchcock, who invented his own genre. Say it of both Vincente Minnelli (Musicals) and John Ford (Westerns), though they would tell you they were just doing their jobs in the studio and dismiss the auteur label. Clint Eastwood, who took the traditional Western and ran with it, sunset-ed early (to belabor the cowboy cliché) with Unforgiven (1992). He continued making movies, but he'd said his last word about that genre.

The same can't even be said of Scorsese's "New Hollywood" cohorts, the crew he came up with. Lucas cashed out. DePalma burned out. Coppola withdrew (his recycled Godfather Part III only took what was once innovative—i.e. Gordon Willis' lush cinematography—and commodified it into a "look"). Their visions were dynamic but incomplete, sometimes even completed by others. Only Steven Spielberg has the sustained excellence that caps off a life making movies, in his autobiographical The Fablemans.

In a way The Irishman can be read as autobiographical, too. Scorsese grew up in and relates so completely to this lifestyle, these characters, and this medium. It's appropriate that the film portrays an entire career (albeit ill-spent) that has played itself out on its own terms.

With traditional ("legacy") filmmaking being replaced by stealthy CGI, The Irishman stands out for its poignancy and grace. Its CGI flourishes go beyond smoothing out DeNiro's wrinkles, to canny use in several sequences, like the dumping of taxi cabs into the river, and the massive crowds at Jimmy Hoffa's rallies. Scorsese has always used technical advances that will aid, and not overwhelm, his art. As far back as Kundun (1997), he's incorporated digital backgrounds. His awestruck praise of mat paintings in Michael Powell's Black Narcissus sweetens his DVD commentary for that film. Movies are magic. They are an illusion of motion. And in Scorsese's hands the illusion is a living, breathing thing.

As I said, I first saw The Irishman on a big screen in its original release, in one of its few showings prior to joining the Netflix queue. There were only a few people in the theater. Projected that big, the flaws in the film were evident, but so are the virtues. The scenes roll out—bap, bap, bap—but the pace was languid, punctuated by Robbie Robertson's mournful harmonica refrain. I sunk back into my seat as if lowering myself into a warm bath and just let it wash over me.

I felt the same the other night, at home on a 55-inch flat screen. Even though Scorsese will keep making movies, The Irishman might well be the culmination of his career. He got the old gang back together one more time, and it won't happen again. People cash out, burn out, and withdraw. But to have produced a film so rich, and so much of a piece with what he's done before—to be able to end as passionately as he began in the medium that he loves—is a rare and wonderful thing.

So: thinking these deep thoughts, I saw the end credits of The Irishman come up. I checked the clock: 5:28. Just a few minutes, I told myself when I turned it on, and I'd watched the whole thing.

Who was I kidding? If it's on and it’s Scorsese, I watch it to the end.