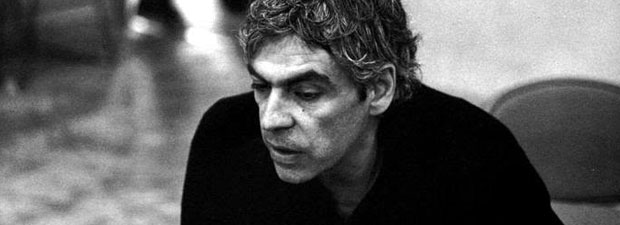

In 1997, Pedro Costa (above), at the age of 38, began a trilogy exploring Portugal's impoverished, an undertaking that would continuously draw raves from the more erudite critics around the world. First came Ossos, which was pursued by In Vanda's Room (2000) and Colossal Youth (2006). These films, often showcasing the same characters, are sublimely visual, meditative masterworks that paint within shadows the seemingly plotless lives of the drug-addled inhabitants of a ghetto that is slowly being dismantled.

The Film Society of Lincoln Center last week had a retrospective of these early works plus other tidbits of Costa's oeuvre, a sort of celluloid foreplay leading to the release of Costa's latest effort, Horse Money. The accompanying press release for this tribute notes that "Costa is now widely regarded as one of the most important artists on the international film scene," and the Film Society's Director of Programming, Dennis Lim, added, "Simply put, nobody makes films like him -- both in terms of his radical methodology and the ravishing results."

This is clearly a sounding of the trumpet for those hungry for a more challenging cinema. Yes, if Antonioni's Red Desert (1964) or Clare Denis's Beau Travail (1999) tickle your fancy, Costa's handiwork might be right up your alley. But, warns Costa aficionado Eric Kohn of indieWire in one review, although the rewards are great, the helmer's "lengthy exchanges are tough to endure." The A.V. Club's Scott Tobias notes, in his review of The Criterion Collection of the above films, there is an "unrelieved tediousness that comes as a consequence to his rejection of any and all narrative architecture." Meanwhile, Jamie S. Rich on his blog, Criterion Confessions, adds that Costa is "a bit of a difficult puzzle."

Of the three, Ossos is easily Costa's most approachable work and his last to utilize the common equipment and techniques of "Hollywood" filmmaking. In the Fontainhas district of Lisbon, immigrants from the former colonies of Portugal are scavenging out a survival, but like the gone-to-ruin buildings they reside in, the gone-to-ruin souls have little chance of triumphing.

Here Tina (Maria Lipinka) has just given birth. Leaving the hospital, she states in disbelief, "I came here as one." Her baby seems to be not a joyful addition to her existence but a cutting away of her flesh. Returning to her achromatic home, she lays the infant down on a couch, drags over a gas tank, turns the knob, and waits for the end. Her endeavor miscarries.

The father (Nuno Vaz) eventually shows up and absconds with the child, which he hopes to use as a beggar's tool, and if that fails, the kid's up for purchase.

Trying to remedy the situation is Tina's neighbor Clotilde (the remarkable Vanda Duarte), a housecleaner who threatens the dad with murder if he hurts her friend.

What follows is a series of long and moderate takes, often wordless, which are remarkable in their passive beauty. Costa doesn't so much direct a scene as he paints a scene. There's a shot where the young man places his head under a kitchen faucet to gulp water and another where the camera sidles up to him as he walks down a rather long street with the unseen baby in a bag. There is no need for dialogue. The shots tell all while creating a sense of foreboding and at times a sleepy sexual tension. The film is riveting.

The 170-minute-long In Vanda's Room surprisingly, or maybe not, surpasses Ossos in its enveloping visual appeal. Seldom has the unlit, mundane world of the penniless been so seductive. Shooting with a digital video camera, Costa returned to Fontainhas to chronicle the final moments of its inhabitants as their buildings are torn down one by one.

Vanda Duarte stars as Vanda Duarte, which has caused more than a few critics to designate this effort as a documentary, while others have sidled up to the term docu-fiction. Duarte, who is lean and curveless with an embattled allurement, is the centerpiece here, lying on her seldom-left bed, noting, "This is good smack!" Otherwise, she's helping a friend unravel a crewel of yarn, cutting up coke, or listening to gossip: "He's staying where that girl lived who killed her baby." One visitor offers up his finch for sale.

Peopled with nonprofessional actors, some just there to show off their vastly compelling visages, an episode might follow where a man is showering in the shadows with only his silhouette visible. Another has a young gent sitting in a blackness with only his crutches and the sandwich he is eating visible. Suddenly, he beseeches a higher power with "May the Lord help me." Other times empty rooms will be viewed by a static camera as a cacophony of smashing cranes and sledgehammering workers fills up the soundtrack.

The effect is hypnotic, and the film ends as it opens without a rationale, or maybe that is the rationale: that there is no true start or conclusion to these lives, just an unending continuance. And when one dies, she will be replaced . . .or not.

Colossal Youth (2006) continues the saga with several of the same characters, but the focus here is on septuagenarian Ventura, who wanders about from the remnants of Fontainhas district to the antiseptic housing projects where he is being offered an apartment. To and fro he treads, communing with his children, one of whom is Vanda. But are they his children?

Early on, outside a shut door, he declares in a monotone delivery to one of his daughters, "Your mother's gone. She doesn't want to spend the rest of her life with me. She doesn't want to move to the new place. She fought me every night. It's been like a nightmare . . . . Every time your mother gave birth, she'd pray it wouldn't be a drunk like me."

A voice replies, "Ventura, you got the wrong door."

Later on, when he tells Vanda about his marital strife with her mom, she notes her mother is buried in a cemetery.

Once again, as noted by Reehan on his blog, "Distant Voices," Costa is continuing in his obliteration of "the behemoth that is the narrative cinema." But if you're not already a fan of Costa by now, joyfully mainlining on his existential aesthetic, you's better sidestep this one.

Now comes Horse Money (2014), an unnecessary addition to the Fontainhas trilogy, and one unequal in execution. Costa has exchanged docu-fiction for pedestrian enactments of one man's non compos mentis musings. Ventura is back again, locked in an infirmary of sorts. When asked his age, he replies, "Nineteen and three months." When lying in bed, he converses with the friends, co-workers, and fellow revolutionaries of his past life, all dead.

Later, he is stuck in an elevator with a soldier holding a rifle whose flesh is painted a sort of dark silvery gray. In this rather longish scene, Ventura recites his prayers: "Our Lord of Nazareth. Son of the Holy Mary, taste the Virgin's milk. The Beast's gun is not yours. Prime Minister, bankruptcy." The soldier, whose lips do not move, replies, "You're worshipping Satan, boy?!"

Little of the film makes sense, and that probably was Costa's intention. In fact, at last year's New York Film Festival, the venue's interviewer told the director, "I've seen the film now three times and I really don't feel I have a grasp of it."

Costa replied that he himself was only now, when chatting about Horse Money, trying to unearth its purport: "I didn't have time to think about it when I was doing it."

So if you are in the mood for self-indulgent befuddlement, although a befuddlement with grand intentions, the summing of up an impoverished life and world, run on over to Lincoln Center.

However, if you want to discover a unique voice and a transformative cinema, seek out the Fontainhas trilogy released now, as noted, on DVD as part of The Criterion Collection.