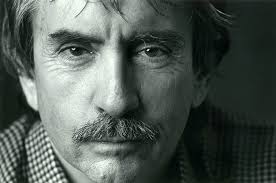

"I'm the end of the line," Arthur Miller once asserted. "Absurd and appalling as it may seem, serious New York theater has died in my lifetime."

Many might argue otherwise. In fact, the best proof that theatre is still alive and kicking is Focus on Playwrights, the new coffee-table book, the cover of which showcases the life-crinkled face that once overlooked the birth of A View from the Bridge, All My Sons, and The Crucible. Yes, photographer Susan Johann’s scintillating collection of over 90 playwrights, whom she’s shot over 20 years -- and the inclusion of sharply revealing interviews with some of the same, is the best retort to anyone ready to cremate modern drama.

Some of those captured for publications such as Vogue and the New Yorker are now deceased (e.g. August Wilson, Edward Albee, and Joe Chaikin) while others are very much functioning (e.g. David Henry Hwang, Lisa Kron, and Nicky Silver).

Johann notes in her text that Tennessee Williams once avowed that photography was "frozen literature." Does she agree with that assumption, and does it apply to her portraits of the likes of William Finn and Tina Howe?

"I hope. I hope," Johann laughs during a recent phone chat. "I was actually waitressing in a restaurant on 42nd Street, the West Bank Café, and Tennessee Williams came in. Now this was ten years before I started this series, and I hadn't even become a photographer, but I remember that day. It was so frightening to me because I've always loved the idea of these playwrights, all of the playwrights. They are the center of it all, whether it's Euripides or Shakespeare or Albee or Miller.

"So Williams walked into the restaurant, and I remember the day. I mean I know what the light was like, and how he was sitting at the front window at a circular table, and how there was somebody who took and made a copy of his credit card bill so he could have Tennessee Williams’s signature because that was so cool. I wish I had known. I wish I had known. I would have followed him around and made sure I got a picture. I think he would have been acceptable to that because he was an accessible kind of person as most of these people have been."

"So Williams walked into the restaurant, and I remember the day. I mean I know what the light was like, and how he was sitting at the front window at a circular table, and how there was somebody who took and made a copy of his credit card bill so he could have Tennessee Williams’s signature because that was so cool. I wish I had known. I wish I had known. I would have followed him around and made sure I got a picture. I think he would have been acceptable to that because he was an accessible kind of person as most of these people have been."

Years later, the very first playwright Johann targeted her lens on was the Tony-winning Christopher Durang, America's most sardonic wit. The author of Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike has noted that folks are always surprised when they first meet him because he looks neither "wild nor angry."

"That's what propelled me. Yes. Yes," Johann enthuses. "Because I read his plays and was laughing so hard, I expected a really outrageous kind of person. And, of course, Chris is very soft-spoken and easy going. You don't see any of that [Durangian outrageousness] on the surface. It comes out in the plays he does, and I guess he’s not really crazy; it's just his ability to see that the world is crazy. Afterwards, I wondered if other playwrights were like that. Do they look like you think they would look like? Or are they all very different from that? That's why I took the pictures."

Perusing Focus on and off again for several weeks, I realize I might never have seen an image of Tom Stoppard before or one of Lanford Wilson or Paula Vogel, or I have and they just haven’t registered. Playwrights are an invisible breed, possibly by choice. Of course, a few break that mold like Sam Shepard or Everett Quinton who both act on stage, in film, or get involved with Jessica Lange.

But what do these first-rate, beautifully reproduced, black-and-white shots actually reveal?

Take David Drake, best known for The Night I Kissed Larry Kramer, who was photographed in 1992 at the age of 29, in a motorcycle jacket, with his right hand reaching out. He’s highly attractive with a strong chin. His eyes, which might be blue, seem to begging the viewer for something of immediate, deep value. His lips are parted as in mid-speech. "What?" you want to respond.

Duane Michals, a fellow photographer, has noted that his art "does deal with 'truth' or a kind of superficial reality better than any of the other arts, but it never questions the nature of reality -- it simply reproduces reality. And what good is that when the things of real value in life are invisible?"

Duane Michals, a fellow photographer, has noted that his art "does deal with 'truth' or a kind of superficial reality better than any of the other arts, but it never questions the nature of reality -- it simply reproduces reality. And what good is that when the things of real value in life are invisible?"

Well, the task of the playwright is to make the invisible visible on stage, and the aim of Johann’s imagery seems to desire to capture the physical dimension of that ability.

As Susan Sontag once avowed, "To take a photograph is to participate in another person's mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time's relentless melt." Yes, if you meet up with some of Johann's subjects now and compare them to the portraits of their earlier selves, you can clearly see how they've weathered life in the theatre. But also, these pictures are indelibly connected to the memories of the plays you've read and seen, works that quite possibly supplied you with insights into their times of presentation and your own once youthful soul. Like the playbills in your closet, these shots help recall productions that bit or soothed: Jonathan Harvey’s Beautiful Thing. Wendy Wasserstein's The Heidi Chronicles. John Guare's Six Degrees of Separation.

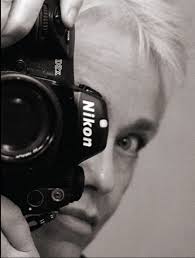

When Johann first started photographing professionally, she did so for magazines or for individuals with specific needs. "But with this playwrights series," Johann recalls, "I could investigate for myself completely. I didn't have to answer to anyone. I could form the shots the way you would form a piece of literature because I was basically going into myself to get a connection with somebody else. So from individual to individual, I was trying to figure out their lives. And, of course, it was a wonderful opportunity to follow a dream, to do something that somebody else wasn't doing at the time.

"When I talk to the playwrights about how they write," she continues, "they often talk about how the plays come out. They don’t know what the next line is going to be, and the characters tell them. And that's what happens in the photo sessions. They tell me what the picture is going to be. I don’t necessarily know at the start . . . . That's the exciting thing for me, to show you how dynamic and wonderfully expressive these people are both in their public and private lives."

If that's Johann's mission, she has succeeded superbly.