This week I wrap up my response to Anthony Tommasini's silly ten best composers list in The New York Times. I'm aware that on an absolute level my list is just as silly; it's not definitive (no list could be), undoubtedly omits worthy composers, etc. I write a mere paragraph when every composer here should have (and often has had) a whole book devoted to him/her. I console myself with the thought that at least my less obvious list serves a purpose by perhaps leading readers to investigate composers they haven't gotten to yet, and by recommending recordings.

Remember, my list proceeds in alphabetical order (if you need to catch up, the first half is here), doesn't rank composers except by vaguely establishing tiers loosely indicated by the amount of recommendations, and doesn't arbitrarily omit any sections of music history.

And, remorseful about omissions even before finishing my list, I have thrown in a coda with enough additional worthies to bring the count to an even 150.

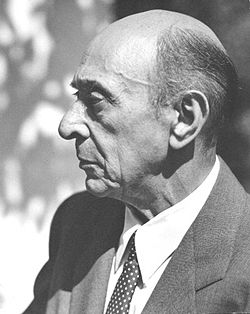

Claude Debussy (1862-1918)

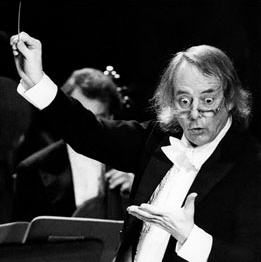

The primary Impressionist (though he didn't like the term) easily made Tommasini's list, as well he should. No music before the 20th century did more to overthrow traditional harmony with its use of pentatonic and whole-tone scales and non-tonal parallel chords, yet what was once radical and reviled is now cozily beloved, and Debussy (pictured above) is generally considered France's greatest composer.

Orchestral Works I: La Mer; Nocturnes; Prélude à l'après midi d'un faune; Marche écossaise; Berceuse héroïque; Musiques pour Le Roi Lear; Images for Orchestra; Jeux; Printemps: Michel Sendrez & Fabienne Boury/Orchestre National de l'O.R.T.F./Jean Martinon (EMI Classics)

Orchestral Works II: Children's Corner Suite; Petite Suite; Danses sacrée et profane; La Boîte à joujoux; Fantaisie for Piano & Orchestra; La plus que lente; Clarinet Rhapsody; Saxophone Rhapsody; Khamma; Danse: Marie Claire Jamet/Aldo Ciccolini/Guy Dangain/Jean Marie Londeix/Orchestre National de l'O.R.T.F./ Jean Martinon (EMI Classics)

Preludes for Piano, Books I & II: Paul Jacobs (Nonesuch)

Pelléas et Mélisande: Maria Ewing/François Le Roux/José Van Dam/Jean-Phillipe Courtis/Christa Ludwig/Patrizia Pace/Rudolf Mazzola/Vienna Philharmonic/Claudio Abbado (Deutsche Grammophon)

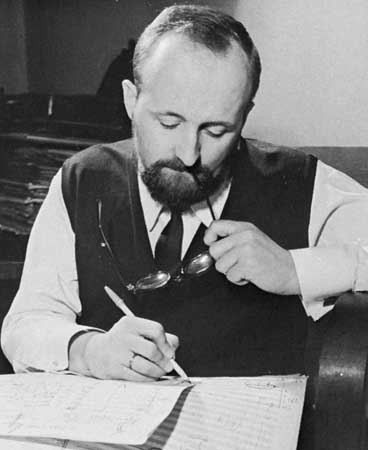

Richard Strauss (1864-1949)

Strauss said near the end of his life, "I may not be a first-rate composer, but I am a first-class second-rate composer." Maybe he had a premonition of Tommasini's list! One would need to be operating on a pretty tight definition of "first-rate" to exclude this master of orchestration who expanded the Wagnerian sound-world even further and brought the art of the tone poem to new heights.

Also sprach Zarathustra; Till Eulenspiegels lustige Streiche; Tod und Verklärung; "Dance of the Seven Veils" from Salome: Staatskapelle Dresden/Rudolf Kempe (EMI Classics)

Elektra: Hans Hotter/Astrid Varnay/Leonie Rysanek/Helmut Melchert/Gertie Charlent/Marlies Siemeling/Marianne Schroeder/Kathe Moller-Siepermann/Heiner Horn/Res Fischer/Helene Petrich/Käthe Retzmann/Hasso Eschert/Arno Reinhardt/Ilsa Ihme-Sabisch/Trude Roesler/Cologne Radio Chorus & Symphony Orchestra/Richard Kraus (Koch)

Albéric Magnard (1865-1914)

My second "underrated," another master symphonist. We might have had more from Magnard if not for World War I; he was killed by the German army, valiantly if foolishly defending his house single-handedly. Not only did this obviously end his productivity, but his house burned and many unpublished works were destroyed.

Symphonies Nos. 3 & 4: BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra/Jean-Yves Ossonce (Hyperion)

Carl Nielsen (1865-1931)

Widely considered Denmark's greatest composer, Nielsen's music might be too quirky for more than cult popularity, but the unusual programs of some of his symphonies make for distinctive listening.

Symphonies Nos. 4-6; Little Suite; Hymnus Amoris: San Francisco Symphony/Herbert Blomstedt (Decca)

Jean Sibelius (1865-1957)

The man who put Finland on the music map, and as a fervent nationalist, that's an apt legacy. He started out influenced by Tchaikovsky, but by his Third Symphony had started moving to a sterner, less overtly rhapsodic style that culminated in the tight-knit conciseness and stark textures of his single-movement Seventh Symphony.

Symphonies Nos. 1-7: Lahti Symphony Orchestra/Osmo Vänskä (Bis)

Erik Satie (1866-1925)

Satie was mostly a miniaturist, partly a result of his rejection of thematic development and sonata form. Various of his musical phases influenced Debussy, Ravel, Poulenc, Milhaud, and more, and he became something of an icon of irony with such work titles as "Desiccated Embryos."

Gymnopedies; Gnossiennes; Nocturnes; La Belle Excentrique; 3 Morceaux en forme de poire; etc.: Aldo Ciccolini (EMI Classics)

Albert Roussel (1869-1937)

Roussel got a late start, not beginning intensive musical study until age 25. After starting out under the spell of the Impressionists Roussel came to favor thicker textures, more formally structured work, masterful counterpoint, and neo-classicism. Writing more densely than most of his countrymen but more piquantly than their Austro-Germanic opposites, he found a distinctive middle ground and tilled it productively.

Symphonies Nos. 3 & 4; Piano Concerto; Bacchus et Ariane: Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Concervatoire/André Cluytens; Orchestre National de France/Georges Prêtre (EMI Classics) Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915)

Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915)

The Russian, mystical, synesthetic Scriabin wrote almost entirely for solo piano or orchestra (the few small exceptions were early and unpublished). The unusually ambiguous and dissonant harmonies of the music of Scriabin's last four years (mostly for piano) project a demonic intensity unlike anything else in music. Listening to these eldritch pieces, it's hard to believe they're by the same guy who started out imitating Chopin. Even the quiet works, such as the Poemes, Op. 69, are profoundly disturbing. When he really cuts loose, as in "Vers la flamme" (Towards the flame), it still sounds avant-garde a century later, weird yet compelling ecstasy. With a whole orchestra to work with, the music's even more extravagantly colorful, though only Prometheus and The Poem of Ecstasy are late enough for the harmonies to run wild.

Late Piano Works: Poème-Nocturne, Op. 61; Sonata No. 6, Op. 62; 2 Poèmes, Op. 63; 3 Etudes, Op. 65; 2 Preludes, Op. 67; 2 Poèmes, Op. 69; Sonata No. 10, Op. 70; 2 Poèmes, Op. 71; Vers la flamme, Op. 72; 2 Danses, Op. 73; 5 Preludes, Op. 74: Roger Woodward (Etcetera)

The above is recommended for its focus on the late piano works, but what I really want to recommend is a two-LP set by Mikhail Rudy on the French label Calliope. It has all the pieces on Woodward's disc plus the Sonatas Nos. 7-9. But the Rudy CD didn't include the whole program [wouldn't fit], and it's not on iTunes, so pick up a complete Sonatas set -- Vladimir Ashkenazy (Decca), Ruth Laredo (Nonesuch), Håkon Austbø (Brilliant Classics or Simax, parts 1 and 2), or Marc-André Hamelin (Hyperion).

Symphonies Nos. 1-3; Piano Concerto; Prometheus: The Poem of Fire; The Poem of Ecstasy: Peter Jablonski/Berlin Deutsches Sinfonie-Orchester/Vladimir Ashkenazy (Decca)

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958)

Until the 1930s Vaughan Williams was a paragon of Englishness in music, collecting English folk songs and carols, compiling the English Hymnal, and editing the music of Purcell. He was not parochial, however, studying with the German Max Bruch and the French Maurice Ravel (the latter actually younger than Vaughan Williams, but a quicker developer; RVW, on the other hand, didn't have his first publication until he was 30). But in the 1930s the very English flavor of his work diminished, his harmonies became more dissonant; of his Fourth Symphony (the only one of his compositions that he conducted for recording), he said, "I don't know if I like it, but it's what I meant." Without a doubt he is England's greatest composer of symphonies.

Symphonies Nos. 1-9; Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis; The Wasps: Aristophanic Suite; Serenade to Music; In the Fen Country; The Lark Ascending; Norfolk Rhapsody No. 1; English Folk Songs Suite; Fantasia on "Greensleeves"; Concerto for Two Pianos & Orchestra; Job: A Masque for Dancing: Norma Burrowes/New Philharmonia Orchestra/London Philharmonic Choir & Orchestra/Adrian Boult (EMI Classics)

Mass in G Minor; Lord Thou hast been our refuge; Prayer to the Father of Heaven; O vos omnes; O clap your hands; O taste and see; Anthem: O how amiable; Hymn: Come down, O Love divine (Down Ampney): Elora Festival Singers/Thomas Fitches/Noel Edison (Naxos)

Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943)

Years ago, when RCA issued the box set of almost all of Rachmaninoff's recordings (everything but alternate takes, I believe), I raved to a pianist friend about how great it was, and she said, ever so snarkily, "Yes, he's such a great pianist, he can even make his own music sound good." A Romantic when modernism was the next big thing, a composer of crowd-pleasing virtuoso music in an era when the hip move was to be neither crowd-pleasing nor virtuoso, he doesn't get the respect he deserves, but his Second and Third Piano Concertos remain iconic, with the latter's technical challenges practically a rite of passage for young pianists.

Piano Concertos Nos. 1-4; Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini: Sergei Rachmaninoff/Philadelphia Orchestra/Leopold Stokowski, Eugene Ormandy (RCA Victor)

Franz Schmidt (1874-1939)

Though he used to be underrated everywhere but his native Austria, the CD boom brought Schmidt's post-Brucknerian symphonies and his apocalyptic oratorio The Book with Seven Seals multiple recordings and international attention.

Symphonies Nos. 1-4: Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Detroit Symphony Orchestra/Neeme Järvi (Chandos)

Charles Ives (1874-1954)

The first great American composer pioneered polytonality, quarter-tones, tone clusters, and more. He used musical quotation extensively, which helps to ground his avant-gardisms in folk music. His Piano Sonata No. 2, "Concord, Mass., 1840 60" and his song "The Housatonic at Stockbridge" are especially masterful.

Piano Sonata No. 2, "Concord, Mass., 1840 60"; Songs: "The Things Our Fathers Loved"; "The Housatonic at Stockbridge"; "From the Swimmers"; "Memories"; "Ann Street"; "Serenity”; "1, 2, 3."; "Songs my mother taught me"; "The Circus Band"; "The Cage"; "The Indians"; "Like a Sick Eagle"; "A sound of a distant horn"; "September"; "Soliloquy (or A Study in 7th and Other Things)"; "A Farewell to Land"; "Thoreau": Pierre-Laurent Aimard/Susan Graham (Warner Classics) Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951)

Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951)

Schoenberg was both a revolutionary modernist -- which is certainly how he was seen by those who resisted his influence and vilified his new method of musical organization (12-tone/serialist) -- and an arch-Romantic whose dissolution of traditional harmony represented the ultimate evolution from Wagner's and Mahler's chromatic dissonances; he drew equally from Brahms and the concept of "developing variation" (which term Schoenberg coined). Certainly dichotomies between emotion and intellect are falsely applied to Schoenberg's music; his intellectually justified dissonances are highly expressive.

Concerto for Piano & Orchestra, Op. 42; 3 Piano Pieces, Op. 11; 6 Piano Pieces, Op. 19; 5 Little Piano Pieces, Op. 23; Suite for Piano, Op. 25; 2 Piano Pieces, Op. 33a & 33b: Maurizio Pollini/Berlin Philharmonic/Claudio Abbado (Deutsche Grammophon) [also includes Webern: Variations, Op. 27]

Verklärte Nacht (Transfigured Night); Pelleas und Melisande: Berlin Philharmonic/Herbert von Karajan (Deutsche Grammophon)

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937)

The epitome of Gallic elegance, Ravel was not prolific, but almost everything he wrote is a highly polished gem. Nowhere is the scintillating character of his music better displayed than in his piano works. He is arguably the most popular French composer: the French rights agency SACEM reports that his music earns more in royalties than anyone else's. Taking into account how little of it there is, relatively speaking, this indicates what a high percentage of his music is standard repertoire.

Piano Concertos; Valses Nobles et Sentimentales: Krystian Zimerman/London Symphony Orchestra/Cleveland Orchestra/Pierre Boulez (Deutscje Grammophon)

Complete Music for Solo Piano: Valses Nobles et Sentimentales; Gaspard de la nuit; Miroirs; Le Tombeau de Couperin; À la manière de Borodine; Menuet antique; À la manière de Chabrier; Menuet sur le nom de Haydn; Sonatine; "Pavane pour une Infante défunte"; Jeux d'eau; Prélude; La Valse: Abbey Simon (Vox) Béla Bartók (1881-1945)

Béla Bartók (1881-1945)

Another of Tommasini's Ten. The rhythms, harmonies, and modes of the Magyar peasant music found in Bartók's native Hungary pervade his music, which is not too surprising considering his considerable exertions going around the country making field recordings. But plenty of nationalist composers incorporated folk music into their work, including fellow Hungarians; few sounded as distinctively piquant as Bartók.

Concerto for Orchestra; Music for Strings, Percussion, & Celesta; Hungarian Sketches: Chicago Symphony Orchestra/Fritz Reiner (RCA Living Stereo)

String Quartets: Emerson String Quartet (Deutsche Grammophon)

Complete Music for Solo Piano: György Sandor (Vox)

Karol Szymanowski (1882-1937)

The greatest Polish composer since Chopin was almost his diametrical opposite, excelling in vocal and symphonic music and dissolving traditional harmony into tonal ambiguousness. His best works are dazzlingly colorful and ravishingly beautiful in their richly luxuriant harmonic textures and orchestral timbres.

Symphony No. 3, "Song of the Night"; Stabat Mater; Litany to the Virgin Mary: Jon Garrison/Florence Quiver/Elzbieta Szmytka/John Connell/City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra & Chorus/Simon Rattle (EMI Classics)

Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971)

Another on Tommasini' s list. We are lucky that Columbia Records instituted such a close relationship with Stravinsky; I can think of no other composer who conducted so much of his music for one company over so long a period of time. And unlike, say, Copland, whose recordings, though insightful, were mostly surpassed by professional conductors, Stravinsky's recordings are often definitive even in his best-known and most-recorded pieces, such as the famous The Rite of Spring; he gives them a keenly pointed focus and acerbic bite that conveys their unique character better than the more dramatic effusions of, say, Leonard Bernstein (to cite the conductor who most surpassed Copland's work).

s list. We are lucky that Columbia Records instituted such a close relationship with Stravinsky; I can think of no other composer who conducted so much of his music for one company over so long a period of time. And unlike, say, Copland, whose recordings, though insightful, were mostly surpassed by professional conductors, Stravinsky's recordings are often definitive even in his best-known and most-recorded pieces, such as the famous The Rite of Spring; he gives them a keenly pointed focus and acerbic bite that conveys their unique character better than the more dramatic effusions of, say, Leonard Bernstein (to cite the conductor who most surpassed Copland's work).

The Original Jacket Collection: Stravinsky Conducts Stravinsky - the Classic LP Recordings: Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rite of Spring); L'Oiseau de feu (The Firebird); Symphony of Psalms; Symphony in C; Firebird Suite (1945 revision); Petrushka Suite; Fanfare for 2 Trumpets; The Owl & the Pussycat; Septet; Movements for Piano & Orchestra; Anthem: "The dove descending breaks the air"; Double Canon "Raoul Dufy in Memoriam"; Epitaphium; Elegy for J.F.K.; Cantata: A Sermon, a Narrative, and a Prayer; L'Histoire du Soldat Suite; Pulcinella Suite; Preludium for Jazz Band; Pastorale: Chant sans paroles; Rag-Time for 11 Instruments; Tango; Concertino for 12 Instruments; Ebony Concerto (2 versions; w/Benny Goodman, Woody Herman); The Star-Spangled Banner; Four Russian Songs; Four Russian Peasant Songs; Renard: Histoire Burlesque; Zvezdoliki; Babel; Ave Maria; Credo; Pater Noster; Chorale & Variations on "Von Himmel hoch"; Fireworks; Ode, elegiacal chant; Four Norwegian Moods; Circus Polka; Russian Maiden's Song: Adrienne Albert, Benny Goodman, CBC Symphony Orchestra, Charles Brady, Columbia Symphony Orchestra, Don Christlieb, Dorothy Remsen, Festival Singers of Toronto, George Shirley, Gregg Smith Singers, Israel Baker, Laurindo Almeida, Loren Driscoll, Louise Di Tullio, Richard Kelly, Robert Marsteller, Roy d'Antonio, Columbia Jazz Ensemble, Igor Stravinsky (Columbia)

Anton Webern (1883-1945)

One of the three greats of the Second Viennese School (that is, of the eventual 12-tone composers centered around Schoenberg), Webern was its most extreme miniaturist, the icon of a stylistic revolution that by presenting musical experiences in their most concentrated and concise forms made exacting attention to every facet (including texture and timbre) of the performance a necessity. It's an aesthete's approach, but given the brevity of the pieces, not exhausting to listeners, and in fact quite rewarding, teaching a whole new way of listening and enjoying music. Eventually it led to "total serialism," which could seem an arid exercise at times, but the experiential intensity of Webern's music was certainly anything but dry.

Symphony; Six Pieces for Large Orchestra; Five Canons for Soprano & Two Clarinets; Three Traditional Rhymes; Three Songs, Op. 18; Trio; Quartet; Variations for Piano; Four Pieces for Violin & Piano; Three Pieces for Cello & Piano; Concerto for Nine Instruments: Twentieth Century Classics Ensemble/Jennifer Welch-Babidge/Philharmonia Orchestra/Robert Craft (Naxos)

5 Pieces, Op. 10, 5 Sacred Songs, 2 Songs, Op. 8; 4 Songs, Op. 13; 6 Songs, Op. 14; 2 Songs, Op. 19; 5 Movements; Das Augenlicht; Variations for Orchestra; Cantata No. 2: Tony Arnold/Claire Booth/David Wilson-Johnson/Simon Joly Chorale/Twentieth Century Classics Ensemble/Robert Craft (Naxos)

Edgard Varèse (1883-1965)

Varèse was the first significant electronic composer. That his complete extant works (all but one of his early compositions -- before he moved to the U.S. in 1915 -- were lost, destroyed, or burned in a warehouse fire) can fit on just two CDs shows that he was not prolific, but his highly innovative 1920s compositions, which arguably changed the very definition of music, proved extremely influential on musicians ranging from John Cage to Frank Zappa.

Complete Works: Amériques; Offrandes; Hyperprism; Octandre; Arcana; Densité 21.5 for solo flute; Ionisation; Ecuatorial; Nocturnal; Intégrales; Déserts: Asko Ensemble, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra/Riccardo Chailly (Decca)

Alban Berg (1885-1935)

Berg's Romantic and Expressionist take on 12-tone music (with Baroque forms also influencing his work) make his the most accessible serial music. Densely structured, it's on the opposite end of the 12-tone spectrum from Webern's; Berg's Wozzeck is the greatest opera of the 20th century.

Chamber Concerto; Three Pieces for Orchestra; Concerto for Violin and Orchestra: Pinchas Zuckerman/Daniel Barenboim/Saschko Gawriloff/BBC Symphony Orchestra/London Symphony Orchestra/Pierre Boulez (Sony Classical)

Wozzeck: Boje Skovhus, Angela Denoke, Frode Olsen, Jürgen Sacher, Jan Blinkhof, Chris Merritt, Konrad Rupf, Kay Stiefermann, Frieder Stricker, Renate Spingler, Findlay A. Johnstone/Hamburg State Philharmonic Orchestra/Ingo Metzmacher (EMI Classics)

Bohuslav Martinů (1890-1959)

A late bloomer in the sense that it wasn't until his fifties that he essayed symphonies and found his mature style -- though he truly did continue evolving until the end of his career. Romanticism, jazz, neo-classicism, Impressionism, Czech folk music, Baroque concerto grosso style -- all these and more were incorporated. So it almost comes as no surprise that, after he'd moved to France and then fled from the Nazis to the United States, Burt Bacharach was one of his students.

Symphony Nos 3 & 4: Czech Philharmonic Orchestra/Jiri Belohlavek (Supraphon)

Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953)

A child prodigy who at age 13 had composed four operas already, Prokofiev developed a piquantly dissonant style that adheres to no school or system, but tends toward mordant wit. An excellent pianist, he wrote some of his most scintillating works for that instrument.

Piano Concertos Nos. 1-5; Overture on Hebrew Themes; Visions Fugitives: Michel Beroff/Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra/Kurt Masur; Michel Portal/Quatour Parrenin (EMI Classics)

Romeo and Juliet: London Symphony Orchestra/Valery Gergiev (LSO Live)

Complete Music for Solo Piano: Piano Sonatas Nos. 1-9; etc.: Frederic Chiu (Harmonia Mundi)

Arthur Honegger (1892-1955)

Though Swiss, Honegger was born in France and spent much of his life in Paris. Unlike his fellow members of "Les Six," he rejected neither Romanticism nor German music as influences, and thus wrote some of the weightiest music to come out of France in the 1920s-‘40s.

Symphonies Nos. 1-5; "Pacific 231" (Symphonic Movement No. 1); Symphonic Movement No. 3; Prelude for The Tempest of Shakespeare: Czech Philharmonic Orchestra/Serge Baudo (Supraphon) Lili Boulanger (1893-1918)

Lili Boulanger (1893-1918)

The world lost a great composer when Boulanger, younger sister of famed music teacher Nadia Boulanger, had her life cut short at age 24 due to Crohn's Disease. Her instructors included not only Nadia but also Gabriel Faure, and Lili became -- at age 19 -- the first woman to win the Royal Academy's Prix de Rome first prize (Nadia had won second prize five years earlier; their father had won first prize in 1835). Lili had been so precocious that she managed to leave a significant, albeit small, body of her work, which is especially strong in vocal works.

Psalm 24; Faust et Helene; D'un Soir Triste; D'un Matin de Printemps; Psalm 130: Jason Howard/Lynne Dawson/Bonaventure Bottone/Ann Murray/Neil MacKenzie/City of Birmingham Symphony Chorus/BBC Philharmonic Orchestra/Yan Pascal Tortelier (Chandos)

Federico Mompou (1893-1987)

Thanks to jazz pianist Richie Beirach for turning me on to the music of Mompou, and especially for the advice to seek out Mompou's own recordings. If you've ever wanted Satie without the japes or Debussy in sparer yet more concentrated form, here you go. The most delicately ethereal piano music imaginable (but without even the slightest hint of New Age vacuousness, I hasten to reassure, if that description set off warning alarms).

Mompou Plays Mompou: Música Callada: Federico Mompou (Ensayo)

Francis Poulenc (1899-1963)

The second-youngest member of "Les Six" (by a month), Poulenc was at first the most flippant in his music. Then the deaths of several friends led to a deepening of religious conviction, and the combination of wit and faith led to some of the finest religious music of the 20th century.

Mass in G major; Quartre motets pour un temps de pénitence; Quartre motets pour le temps de Noël; Exultate Deo; Salve Regina; Quatre petites prières de Saint François d'Assise; Laudes de Saint Antoine de Padoue; Ave verum corpus: Netherlands Chamber Choir/Eric Ericson (Globe)

Kurt Weill (1900-50)

No classical composer more consistently and innovatively incorporated popular music into his style than this German Jew whose use of music hall jazz rhythms and textures outraged the Nazis (he fled from them twice, first to France and then to the United States). His most famous work is The Threepenny Opera, one of many superb collaborations with Bertold Brecht; Das Berliner Requiem and the vocal ballet The Seven Deadly Sins of the Petty-Bourgeois are equally great.

Kleine Dreigroschenmusik, Mahagonny Songspiel, Happy End, Berliner Requiem, Violin Concerto: Nona Liddell/Mary Thomas/Meriel Dickinson/Michael Rippon/Benjamin Luxon/Ian Partridge/Philip Langridge/London Sinfonietta/David Atherton (Deutsche Grammophon)

Aaron Copland (1900-1990)

The quintessential American composer moved from the confrontational avant-gardism of his early music to a stunningly distinctive populism that is lyrical yet shows some spine. Later in his career he even fit Serial techniques into his style. Unsurprisingly, the middle period works proved most popular, and have aged quite well.

Symphony No. 3; Quiet City: New York Philharmonic/Leonard Bernstein (Deutsche Grammophon)

Appalachian Spring; Billy the Kid: Ballet Suite; "Fanfare for the Common Man"; El Salon Mexico; excerpts from The Tender Land and Rodeo: Boston Symphony Orchestra/Aaron Copland; Philadelphia Orchestra/Eugene Ormandy; Boston Pops/Arthur Fiedler (RCA Victor)

Harry Partch (1901-1974)

Another American iconoclast/outsider who if anything was even more innovative than Ives, constructing new instruments to play music written for a scale consisting of 57 notes to the octave (as opposed to the usual 12, or 24 for Ives's quarter-tone pieces).

Harry Partch Collection, Volume 2: The Wayward; And on the Seventh Day Petals Fell in Petaluma: Thomas Coleman/Danlee Mitchell/Elizabeth Gentry/Gate 5 Ensemble/Jack McKenzie/Harry Partch (CRI)

William Walton (1902-1983)

Though Walton's status as one of England's greatest composers is secure, it's a shame that his best-known work is Façade, music over which the eccentric lyrics of Dame Edith Sitwell are recited. Much better to focus on his more conventional symphonic works; his cantata Belshazzar's Feast is also exemplary.

Symphonies Nos. 1 & 2; Violin Concerto; Cello Concerto; Overture "Portsmouth Point"; Comedy Overture "Scapino": Philharmonia Orchestra/Bernard Haitink; London Symphony Orchestra/André Previn; Ida Haendel/Paul Tortelier/Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra/Paavo Berglund (EMI Classics)

Maurice Duruflé (1902-1986)

One of the greats of the mighty French organ tradition (having paid his dues as Vierne's assistant at Notre Dame); though he worked in several formats, it's his church works that are most important to his legacy. His gentle Requiem in particular is much loved.

Sacred Choral Works/Organ Works, vol. 1: Requiem; Scherzo for Organ, Op. 2; 4 Motets on Gregorian themes; Prélude et fugue sur le nom d'Alain; Notre Père: Béatrice Uria-Monzon/Didier Henry/Michel Piquemal Vocal Ensemble/Orchestre de la Cite/Michel Piquemal/Eric Lebrun (Naxos)

Michael Tippett (1905-1998)

Even if Tippett had not written three fine symphonies (and one not-so-fine), a masterful piano concerto, several excellent operas, etc. -- even if he had stopped composing entirely after the first work that gained him international attention -- he would still be on this list, because that work was the improbable oratorio A Child of Our Time. It was inspired by a political assassination that ignited Hitler's infamous Kristallnacht; this atheist British composer transformed that raw material into an uplifting (albeit troubling and questioning) masterpiece through the incorporation of African-American spirituals.

A Child of Our Time: Faye Robinson/Sarah Walker/Jon Garrison/John Cheek/City of Birmingham Chorus & Symphony Orchestra/Michael Tippett (Naxos) Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

Shostakovich took the Mahlerian symphony – post-modern, referential, occasionally deliberately grotesque – and gave it a Russian flavor and, it has been said, secret anti-Soviet messages (which helps make up for the pro-Soviet stuff he was obliged to put on the surface – sometimes in the same works). In non-orchestral works, where he had a little more freedom, he worked in a far more personally emotional vein, especially in his string quartets. For more on his music, go here.

Symphonies Nos. 1-15: West German Radio Symphony Orchestra; Rudolf Barshai (Brilliant Classics)

String Quartets Nos. 1-15: Emerson String Quartet (Deutsche Grammophon)

Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992)

Messiaen was one product of the French organ tradition whose impact turned out to be strongest in other formats, though one can listen to his sole symphony through the ears of an organist and surmise a connection between his orchestrational choices and the unique sound of French cathedral organs. Three years ago, on his centenary, I looked at more of his music.

Turangalîla Symphony: Yvonne Loriod/Jeanne Loriod/Toronto Symphony/Seiji Ozawa (RCA Red Seal)

Quatour pour la fin du temps (Quartet for the End of Time): Tashi [Peter Serkin/Ida Kavafian/Fred Sherry/Richard Stoltzman] (RCA Victor Gold Seal)

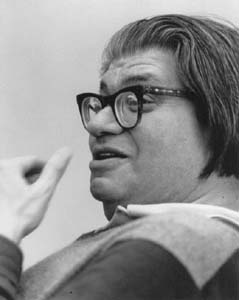

Elliott Carter (1908- )

Note that the date above is correct and that Mr. Carter is not only alive at the time of this writing, he's still actively composing past his hundredth birthday. He's written more from the age of 90 on than some composers on my list managed in their lifetimes. His rhythmically complicated, atonal music – the study of which even generated the new terminology of "metric modulation," which suggests how innovative he's been. It may not ever make inroads among mainstream classical fans, but listeners willing to give it an unbiased listen may find that its counterpoint and conversational aura, well displayed in his strings quartets, offer a way into a sound world full of great rewards.

Complete String Quartets, Vol. 1: Nos. 1 & 5: Pacifica Quartet (Naxos)

Complete String Quartets, Vol. 2: Nos. 2-4: Pacifica Quartet (Naxos)

Samuel Barber (1910-1981)

Barber's best-known piece by far is his Adagio for Strings, arranged for string orchestra from a movement of his String Quartet in B minor. The go-to piece for filmmakers to accompany scenes of grief -- and long before that, played on the radio to mark the passing of President Franklin D. Roosevelt -- it's as perfectly beautiful as could be, but doesn't hint at the bite his other works often have. His post-Romantic lyricism is spiced with just enough dissonance to sound modern.

Adagio for Strings; Medea's Meditation and Dance of Vengence; Overture to The School for Scandal; Second Essay for Orchestra; "Andromache's Farewell"; Intermezzo from Vanessa: Martina Arroyo/New York Philharmonic/Columbia Symphony Orchestra/Thomas Schippers (Sony Classical Masterworks Heritage) John Cage (1912-1992)

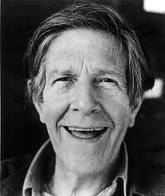

John Cage (1912-1992)

Cage's extreme openness about what can constitute music was most notoriously displayed in his "silent" piece 4'33" -- which, like many of his (slightly) more conventional works, was constructed using chance operations inspired by the I Ching. This openness has helped him inspire several generations of composers in widely disparate styles. One of his most inspired innovations was the "prepared piano": putting various timbre-altering objects on the instrument's strings made it into a self-contained one-person percussion orchestra, as displayed in his Sonatas & Interludes. For more on Cage, here's my overview.

The Complete John Cage Edition, Vol. 14: The Piano Works 2: Sonatas & Interludes: Philipp Vandré (mode)

Benjamin Britten (1913-1976)

Britten's opera Peter Grimes, his Sinfonia da requiem, and his Piano Concerto are masterpieces, but as much as anyone on this list, he owes his place on it to one overwhelming work: his War Requiem. He was a devout pacifist, and in this work written for the reopening of a bombed cathedral, he excelled himself.

War Requiem: Galina Vishnevskaya/Peter Pears/Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau/Bach Choir/Highgate School Choir/Simon Preston/Melos Ensemble/London Symphony Orchestra & Chorus/Benjamin Britten (Decca)

Witold Lutoslawski (1913-94)

In the 1950s, Lutoslawski came up with his own version of 12-tone composition, combined it with what he dubbed "limited aleatorism," and somehow managed to receive awards from his country's Communist government while writing extremely and defiantly "formalist" music. With his music built primarily from manipulation of intervals rather than harmony per se, he then spent nearly four decades composing some of the most individualistic music of his era.

Symphonies Nos. 3 & 4, Les espaces du sommeil: John Shirley-Quirk/Los Angeles Philharmonic/Esa-Pekka Salonen (Sony Classical)

Milton Babbitt (1916-2011)

Compared to the late Milton Babbitt's music, that of Carter and Lutoslawski is practically easy listening. In spite of Babbitt's use of abstruse systems, though (he openly admitted that he wrote for cognoscenti), his work hints at a jazzy sort of energy that listeners with an ear for dissonance will find rather invigorating.

Philomel; "Phonemena"; "Post-Partitions"; Reflections: Robert Miller/Lynne Webber/Jerry Kuderna/Bethany Beardslee (New World)

Iannis Xenakis (1922-2001)

Xenakis certainly has the most interesting biography of anyone on this list since Gesualdo: Born in Greece, he fought in the Resistance against the Nazis and then against the British; he was struck directly in the face by an artillery shell but somehow survived (with severe facial disfigurement). He fled to France and worked as an architect, for which he had been trained (he collaborated with Le Corbusier), meanwhile trying to study music; Nadia Boulanger and Honegger rejected his style, things didn't work out with Milhaud, but Messiaen recognized his talent and gave him free rein. Influenced by Greek folk music, Serialism, and advanced mathematics (including stochastic processes), he built a unique style that also used microtonality and electronics. By picking a piano album, I ease you into his idiom.

Works for Piano: Evryali; Dikhthas; Herma; Palimpsest; Mists; A.R. (Hommage à Ravel); Suite for Piano:

György Ligeti (1923-2006)

Stanley Kubrick liked the buzzing, inhuman grandeur of Ligeti's music so much that he used four of his pieces in the soundtrack for 2001: A Space Odyssey to use four pieces by Ligeti instead. One of them, "Lux aeterna" (Eternal Light), uses the same mensuration canon technique as Ockeghem; its otherworldly sound comes from stacking dissonances so thickly that it's amazing any choir can sing it. (Kubrick used Ligeti pieces in The Shining and Eyes Wide Shut as well.)

Chamber Concerto; Ramifications; String Quartet No. 2; Aventures; Lux aeterna: LaSalle String Quartet; Ensemble InterContemporain/Pierre Boulez; North German Radio Chorus Hamburg/Helmut Franz (Deutsche Grammophon)

Pierre Boulez (1925- )

Boulez was for a while the most doctrinaire of the Serialists, and proselytized strongly for organizing all aspects of composition, not just pitches, using Serial techniques (a concept developed by his teacher Messiaen). Later, looking for more expressiveness, he loosened his strictures. Then, starting in 1957 with Pli selon pli, he even introduced a bit of improvisation into his work (for the conductor, not individual performers). An inveterate reviser, he has produced several versions of and additions to what has become his longest piece, and most recently (1989) removed some of the open-ended aspects; that latest version is listed here.

Pli selon pli: Christine Schäfer/Ensemble Intercontemporain/Pierre Boulez (Deutsche Grammophon) Morton Feldman (1926-1987)

Morton Feldman (1926-1987)

Feldman influenced Cage in his use of indeterminate aspects. He anticipated Minimalism in his early work, and then in his late work embraced something parallel to it but different in its methods. (The recommendation below provides an example of each.) The earlier piece, Rothko Chapel, shows a marvelous mastery of timbres; the later one, Why Patterns?, exhibits two aspects Feldman came to emphasize most, drawing permutations of small patterns out over large time-scales (though he could be much more extreme: his String Quartet No. 2 lasts upwards of six hours) and extremely quiet dynamics.

Rothko Chapel; Why Patterns?: Deborah Dietrich/David Abel/Karen Rosenak/William Winant/UC Berkeley Chamber Chorus/Philip Brett; California EAR Unit (New Albion)

Hans Werner Henze (1926- )

Henze's early works (after a brief flirtation with a neo-Baroque style) were Serialist, but in the '50s he moved away from atonality and incorporated a wide range of musical influences, sometimes influenced by his leftist politics. His symphonies tend to be dissonant, even a bit violent at times, yet overall displaying a sort of colorful sternness and unswerving integrity. No composer since Shostakovich has contributed more powerfully to the continuation of the great symphony tradition.

Symphonies Nos. 1-6: Berliner Philharmoniker, London Symphony Orchestra/Hans Werner Henze (Deutsche Grammophon) Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928-2007)

Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928-2007)

Long the gray eminence of the avant-garde to believers, a subject of vehement controversy to others, the late Karlheinz Stockhausen was a hugely polarizing figure for decades, but also greatly influential. Even the Beatles were influenced (by his electronic music), as well as musicians as wide-ranging as Miles Davis and Frank Zappa, while his students included members of Krautrock band Can. His influence outside of his circle arguably diminished after his decision to abandon his long and successful affiliation with Deutsche Grammophon; he regained the rights to his music and reissued it himself in expensive (but lavish and beautiful) editions available only directly through his company's website. Practicality was not one of his strong points. He wrote a string quartet in which each player performed in a separate flying helicopter, the four players' outputs and the helicopter noise radioed into the concert hall; compared to that, having to mail a check to Germany is small potatoes. Fortunately a few works have been recorded by other performers, most notably his monumental piano cycle Klavierstücke I-XI (though even that is on a German label that lately seems hard to find in the U.S.).

Electronic Music 1952-1960: Kontakte; Gesang der Jünglinge; Etude; Studie I; Studie II: Stockhausen (Stockhausen)

Klavierstücke I-XI: Herbert Henck (Wergo)

Einojuhani Rautavaara (1928- )

The greatest Finnish composer since Sibelius has long gone his own way; even when he used Serial techniques, it was hard to tell since the resulting music sounded tonal. He is best known for large-scale works that are rhapsodic, even calmly ecstatic, and continues to work in standard forms.

Symphony No. 4; Symphony No. 5; Cantus Arcticus (Concerto for Birds & Orchestra): Leipzig Radio Symphony Orchestra/Max Pommer (Ondine)

George Crumb (1929- )

A user of extended instrumental techniques (to create new timbres) and occasionally electronics (usually integrated with instruments), Crumb won a Pulitzer Prize for Echoes of Time and the River, but his best-known work is the 13-movement Black Angels, for amplified string quartet using extended techniques (playing with paper clips and thimbles, etc.), with the members also playing percussion, making vocal sounds, and bowing glasses. The effects are quite visceral, frankly scary at times, and a vivid evocation of the violent era in which it was written: 1970, influenced by the Vietnam War, which led Crumb to inscribe "in tempore belli" (in time of war) on the manuscript when he finished it.

Black Angels; Unto the Hills: Miró Quartet; Orchestra 2001/James Freeman (Bridge)

Tōru Takemitsu (1930-1996)

Takemitsu was drafted into the Japanese in 1944, a shocking and bitter experience for one so young, but it was then that he heard his first Western music. Almost entirely self-taught, he was strongly influenced by Debussy, Webern, Messiaen, Stockhausen, and Cage. After a youthful rejection of Japanese music in a reaction against nationalism, he eventually incorporated his own take on traditional sounds and techniques into his largely Impressionist style.

Requiem for strings; November Steps; Far Calls. Coming, Far!; Visions: Kinshi Tsuruta/Katsuya Yokoyama/Yuzuko Horigome/Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra/Hiroshi Wakasugi (Denon)

Tod Dockstader (1932- )

Most of the early electronic music practitioners were academics with access to university studios. Dockstader was an outsider who was only able to create his tape-based works (using musique concrete) because he worked in a studio as an audio engineer; when the studio went out of business, he was unable to get a university job, despite having had several LPs released, because he lacked academic credentials. But Fellini used music from his first LP for the Satyricon soundtrack, and in the CD era Starkland compiled Dockstader's '60s work on a pair of discs, one of which is recommended below. This enticed Dockstader back into creating music, this time via the more convenient computer.

Apocalypse: Traveling Music; Luna Park; Two Fragments from Apocalypse; Apocalypse; Drone; Four Telemetry Tapes: Tod Dockstader (Starkland)

Krzysztof Penderecki (1933- )

Krzysztof Penderecki (1933- )

Perhaps the most radical of the avant-gardists in post-WWII Poland, Penderecki found international fame in 1960 with the gratingly dissonant string work Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima, full of tone clusters, quarter-tones, and extended techniques that created new sounds and required him to invent a new notational language. In the '70s he stepped back from the avant-garde, but his music remains challenging even when tonal.

Anaklasis; Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima; Fonogrammi; De Natura Sonoris Nos. 1-2; Capriccio; Canticum Canticorum Salomonis; The Dream of Jacob: Wanda Wilkomirska/Krakow Philharmonic Chorus; Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra; London Symphony Orchestra/Krzysztof Penderecki (EMI Classics)

St. Luke Passion: Izabella Klosinska, Adam Kruszewski, Romulad Tesarowicz, Krzysztof Kolberger/Jaroslaw Malanowicz/Warsaw Boys Choir/Warsaw National Philharmonic Choir & Orchestra/Antoni Wit (Naxos)

Morton Subotnick (1933- )

The first electronic composer to write specifically for the phonograph is a lot more than the answer to a trivia question. Echoes of that 1967 LP, Silver Apples of the Moon, commissioned by the Nonesuch label, can even be heard in jazz keyboardist Herbie Hancock's early '70s music with his group Mwandishi. In recent years Subotnick has devoted his time to creating computer programs that allow even non-musicians to improvise music using their computer's mouse to direct aspects of sound.

Silver Apples of the Moon; The Wild Bull: Morton Subotnick (Wergo)

Henryk Górecki (1933-2010)

Górecki was an obscure Polish composer until 1990, when against all odds his Symphony No. 3, three slow movements with soprano soloist, reached the pop charts in England and sold over a million copies. He'd been a Serialist and an avant-gardist, then (like his countryman Penderecki, only moreso) pared away the radical aspects. Often having a religious (specifically Roman Catholic) inspiration, the results were in a sort of Minimalist style, tuneful in a mournful and emotionally moving way.

Symphony No. 3 "Symphony of Sorrowful Songs": Dawn Upshaw/London Sinfonietta/David Zinman (Nonesuch)

Alfred Schnittke (1934-1998)

A polystylistic composer whose imagination ran wild in his often colorful and controversial symphonies, Schnittke (like Shostakovich) had a darker, more private side he exposed in his string quartets. Both styles are ultimately unsettling.

Symphony No. 4; Requiem: Uppsala Akademiska Kammarkör/Stockholm Sinfonietta/Okko Kamu, Stefan Parkman (BIS)

String Quartets Nos. 1-4; Canon in Memory of I. Stravinsky; Collected Songs Where Every Verse is Filled with Grief: Kronos Quartet (Nonesuch) Terry Riley (1935- )

Terry Riley (1935- )

Riley's seminal In C, a 45-minute (or more) piece that fits on a single page of music, kickstarted Minimalism. Consisting of 53 short modules played repetitively but only loosely synchronized among the musicians, resulting in kaleidoscopically shifting patterns, it is one of the most influential single pieces of music. Beyond the classical world, it also has influenced The Who ("Baba O'Riley" is named partly in tribute) and Sufjan Stevens, among others.

In C: Terry Riley/members of the Center of the Creative and Performing Arts in the State University of New York at Buffalo (Sony Masterworks)

Arvo Pärt (1935 - )

The best (by far) of the so-called Mystic Minimalists, this Estonian started out as a'50s/'60s avant-gardist of dissonant proclivities, but in the mid-'70s he stripped his music down to bare essentials in a style he called "tintinnabulism" (evoking the ringing of many tiny bells); over the past decade has been reintroducing touches of his knottier early style. I look at his career and more recommended recordings culturecatch.com/music/arvo-part-on-ecm here.

Tabula Rasa; Fratres; Cantus in memory of Benjamin Britten: Gidon Kremer/Keith Jarrett/Staatsorchester Stuttgart/Dennis Russell Davies/12 Cellists of Berlin Philharmonic/Tatjana Grindenko/Alfred Schnittke/Lithuanian Chamber Orchestra/Saulus Sondeckis (ECM)

Steve Reich (1936- )

One of the interesting things about Minimalism is how different the Minimalists sound from each other. And though one somewhat common tendency is that, to my taste at least, many don't tend to set texts very compellingly, Reich and Pärt are shining exceptions; in fact, The Desert Music is my favorite Minimalist piece.

The Desert Music: Steve Reich and Musicians/Chorus and Members of the Brooklyn Philharmonic/Michael Tilson Thomas (Nonesuch)

Philip Glass (1937- )

The prolific Glass has worked in many standard forms mostly avoided by other Minimalists, with notable successes in opera and the symphony, but the purest essence of his style is found in his soundtracks, especially the iconic Koyaanisqatsi with its alluring textures.

Koyaanisqatsi: Philip Glass Ensemble; Western Wind Vocal Ensemble; Michael Riesman (Antilles)

Charles Wuorinen (1938- )

Wuorinen took the world of modern music by storm as the youngest composer to ever win a Pulitzer Prize, for his all-electronics composition Time's Encomium. Developing a unique style derived from serialism but influenced at times by fractal geometry, he has been fairly prolific by the standards of the avant-garde yet has maintained a high standard of quality.

Time's Encomium; Piano Sonata; String Quartet: Wuorinen; Robert Miller; Fine Arts Quartet (Nonesuch)

Ingram Marshall (1942- )

Mixing Minimalism and electronics in a highly distinctive style, this Subotnick student (who has also written for "normal" instruments) is especially adept at crafting music of deep emotional resonance from seemingly simple materials, as epitomized on the recommended album.

Three Penitential Visions/Hidden Voices: Cheryl Bensman Rowe/Ingram Marshall (Nonesuch) David Lang (1957- )

David Lang (1957- )

The youngest composer on the list (yeah, in classical music, you can be "on the rise" at 54) has tweaked Minimalism into an at times brasher and more confrontational style, but I most love the brooding sound heard on his long work The Passing Measures, where Lang's mastery of contrasting timbres is less flashily and more subtly displayed thanks to the clarinet mastery of Marty Ehrlich.

The Passing Measures: Marty Ehrlich/Birmingham Contemporary Music Group/City of Birmingham Symphony Chorus & Orchestra/Paul Herbert (Cantaloupe)

Extremely Honorable Mention (bringing the total to 150):

Magister Leoninus (c.1135-c.1201)

Magister Leoninus, Vol. 1: Red Byrd/Cappella Amsterdam (Hyperion)

Jacob Obrecht (1450/1-1505)

Missa Maria zart: Tallis Scholars/Peter Phillips (Gimell)

John Taverner (c.1490-1545)

Western Wind Masses by Taverner, Tye, Sheppard: Tallis Scholars/Peter Phillips (Gimell)

Nicolas Gombert (c.1495-c.1560)

Missa Media vita in morte sumus; Motets: Media vita in morte sumus; Salve Regina; Anima mea liquefacta est; O crux, splendidior; Quam pulchra es; Musae lovis: Hilliard Ensemble (ECM)

Cristóbal de Morales (c.1500-1553)

Officium Defunctorum & Missa Pro Defunctis: La Capella Reial de Catalunya/Hespèrion XX/Jordi Savall (Astrée Auvidis)

Tomás Luis de Victoria (1548-1611)

Requiem; Officium defunctorum: Tallis Scholars/Peter Phillips (Gimell)

Orlando Gibbons (1583-1625)

Choral and Organ Music: "O clap your hands"; "Great King of Gods"; "Hosanna to the Son of David"; "Out of the deep"; "Lift up your heads"; Fantasia a 4; etc.: Laurence Cummings/Oxford Camerata/Jeremy Summerly (Naxos)

Girolamo Frescobaldi (1583-1643)

Harpsichord Works, Volume 2: Toccatas, etc.: Richard Lester (Nimbus)

Heinrich Schütz (1585-1672)

Symphoniae Sacrae III: Cantus Cölln/Konrad Junghänel (Harmonia Mundi)

Dietrich Buxtehude (c.1637-1707)

Organ Music, Vol. 1:Magnificat primi Toni; Magnificat noni toni; Chorale Preludes, BuxWV 191, 192, 178, 224, 198, 190; Praeludiums, BuxWV 147, 139, 152, 149: Volker Ellenberger (Naxos)

Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber (1644-1704)

Rosary Sonatas: Andrew Manze/Richard Egarr (Harmonia Mundi)

Padre Antonio Soler (1729-83)

Sonatas for Harpsichord, Vol. 1: Gilbert Rowland (Naxos)

Johann Christian Bach (1735-82)

6 Sinfonias Op.3/6, Piano Concertos Op. 13: Academy of St. Martin in the Fields/Neville Marriner, Ingrid Haebler/Vienna Capella Academica/Eduard Melkus (Philips)

Luigi Boccherini (1743-1805)

6 Symphonies, Op.12: New Philharmonia Orchestra/Raymond Leppard (Philips)

Luigi Cherubini (1760-1842)

Requiem Mass in C Minor: Robert Shaw Chorale/NBC Symphony Orchestra/Arturo Toscanini (RCA)

Gaetano Donizetti (1797-1848)

Lucia Di Lammermoor: Beverly Sills/Carlo Bergonzi/etc./Ambrosian Opera Chorus/London Symphony Orchestra/Thomas Schippers (Deutsche Grammophon)

Hector Berlioz (1803-1869)

Symphonie fantastique; Harold in Italy; Le Corsaire Overture; Béatrice et Bénédict Overture; Roman Carnival Overture; Benvenuto Cellini Overture; Les Francs-Juges Overture: Donald McInnes/Orchestre National de France/Leonard Bernstein/London Symphony Orchestra/André Previn (EMI Classics)

Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901)

Falstaff: Bryn Terfel/Berlin Philharmonic/Claudio Abbado (Deutsche Grammophon)

Bedřich Smetana (1824-1884)

Má vlast (My Fatherland): Boston Symphony Orchestra/Rafael Kubelik (Deutsche Grammophon)

Alexander Borodin (1833-1887)

Symphonies Nos. 1 & 2: USSR Symphony Orchestra/Evgeni Svetlanov (Melodiya)

Edward Elgar (1857-1934)

Violin Concerto; "Enigma" Variations: Yehudi Menuhin/London Symphony Orchestra/Royal Albert Hall Orchestra/Edward Elgar (EMI Classics)

Louis Vierne (1870-1937)

The Six Symphonies for Organ: Pierre Cochereau (Solstice)

Alexander von Zemlinsky (1871-1942)

Lyric Symphony; Opera Preludes & Interludes: Soile Isokoski/Bo Skovhus/Gürzenich-Orchester Kölner Philharmoniker/James Conlon (EMI Classics)

Gustav Holst (1874-1934)

The Planets: Montreal Symphony Orchestra/Charles Dutoit (Decca)

Ottorino Respighi (1879-1936)

The Pines of Rome; The Fountains of Rome; The Birds; Three Botticelli Pictures; Ancient Airs and Dances, Suites 1-3: London Symphony Orchestra/Lamberto Gardelli; Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, Academy of St. Martin in the Fields/Neville Marriner (EMI Classics)

Frank Martin (1890-1974)

Mass for Double Choir; Songs of Ariel; Ode à la Musique; Cantate pour le 1er Août; Chansons (1944): The Sixteen/Harry Christophers (Collins)

Darius Milhaud (1892-1974)

La Création du monde; Le Boeuf sur le toit; Suite Provençale; L'Homme et son désir: Orchestre National de Lille/Jean-Claude Casadesus (Naxos)

Paul Hindemith (1895-1963)

Symphony "Mathis Der Maler"; Concerto Music for Strings & Brass; Der Schwanendreher: Boston Symphony Orchestra/William Steinberg, Daniel Benyamini/Société des Concerts du Conservatoire de Paris/Daniel Barenboim (Deutsche Grammophon)

Ruth Crawford Seeger (1901-1953)

The World of Ruth Crawford Seeger: Piano Sonata; Theme and Variations; Preludes; Five Canons; Kaleidoscopic Changes on an Original Theme, Ending with a Fugue; etc.: Jenny Lin (Bis)

Karl Amadeus Hartmann (1905-1963)

Concerto Funèbre; Sinfonie; Chamber Concerto: Isabelle Faust/Paul Meyer/Petersen Quartett/Munich Chamber Orchestra/Christoph Poppen, (ECM)

Jean Langlais (1907-1991)

Langlais at Notre-Dame de Paris: Maîtrises Notre-Dame de Paris/Quatuor de trombones de Paris/ Jean Langlais (Solstice)

Alan Hovhaness (1911-2000)

Symphony No. 2 "Mysterious Mountain"; Prayer of St. Gregory; And God Created Great Whales; Prelude & Quadruple Fugue; Alleluia & Fugue; Celestial Fantasy: Charles Butler/Seattle Symphony Orchestra/Gerard Schwarz (Delos)

Henri Dutilleux (1916- )

Cello Concerto "Tout un monde lointain"; Violin Concerto "L'Arbre des songes"; Symphony no 2 "Le double"; etc.: Mstislav Rostropovich/Renaud Capuçon/Aude Guirai/Timothee Collardot/Sarah Lecolle/Orchestre de la Société du Conservatoire Paris/Orchestre de Paris/Radio France Philharmonic Orchestra/French Radio New Philharmonic Orchestra/Toulouse Capitole Orchestra /Georges Prêtre/Serge Baudo/Myung-Whun Chung/Michel Plasson (EMI Classics)

La Monte Young (1935- )

The Second Dream of the High-Tension Line Stepdown Transformer: Theatre of Eternal Music/Ben Neill (Gramavision)

Charlemagne Palestine (1945- )

Strumming Music: Charlemagne Palestine (Felmay)

John Zorn (1954- )

Duras: Duchamp: John Zorn (Tzadik)

Erkki-Sven Tüür (1959- )

Flux: Symphony No. 3; Concerto for Violoncello and Orchestra; Lighthouse: David Geringas/Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra/Dennis Russell Davies (ECM)

James MacMillan (1959- )

Symphony No. 2; Sinfonietta; Cumnock Fair: Graeme McNaught/Scottish Chamber Orchestra/James MacMillan (Bis)

Aaron Jay Kernis (1960- )

Symphony No. 2; Musica Celestis; Invisible Mosaic II: City Of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra/Hugh Wolff (Argo) - Steve Holtje