Many consider Dmitri Shostakovich the greatest composer of the 20th century. Born September 25, 1906, he might not have lived past his teens if he hadn't been talented. During the famines of the Revolutionary period in Russia, Alexander Glazunov, director of the Petrograd (later Leningrad) Conservatory, arranged for the poor and malnourished Shostakovich's food ration to be increased. Shostakovich's Symphony No. 1, his graduation exercise for Maximilian Steinberg's composition course at the Conservatory, was completed in 1925 at age 19 and was an immediate success worldwide. He was The Party's poster boy; his Second and Third Symphonies unabashedly subtitled, respectively, "To October" (celebrating the Revolution) and "The First of May" (International Workers' Day).

His highly emotional harmonic language is simultaneously tough yet communicative, but his expansion of Mahlerian symphonic structure, dissonances, sardonic irony, and dark moods eventually clashed with the conservative edicts of Communist Party officials. In 1936 he was viciously denounced by Pravda in an article title "Chaos Instead of Music" after a sexual scene in his opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk offended the prudish Josef Stalin, who with his entourage walked out of the performance. This was not like a Western artist getting a bad review; artists disapproved of by Stalin had a tendency to turn up dead. In fear, Shostakovich withdrew his Fourth Symphony after rehearsals. His seemingly less controversial Fifth Symphony was dubbed "a Soviet artist's creative answer to just criticism," but if the posthumously published memoir Testimony (the authenticity of which is highly controversial) is to be believed, the Fifth's finale is hollow, a secret mockery: "The rejoicing is forced, created under threat."

His Seventh Symphony, the "Leningrad," written while Russia resisted the Nazi invasion and Leningrad underwent a 900-day siege, was smuggled out of the U.S.S.R. on microfilm to be played in the West, where in the anti-German climate of World War II it became a symbol of heroic resistance and so did the composer, depicted on the cover of the July 20, 1942 Time no less, wearing a fireman's helmet in his purported role as fire warden guarding against air raid attacks.

In 1948, his Eighth and Ninth Symphonies were attacked by Tikhon Khrennikov, First Secretary of the Union of Soviet Composers. (The former was considered too dark and therefore defeatist; the latter too trivial and thus not the desired celebration of victory. This Soviet Goldilocks did not, however, find something between them that was "just right.") Against his will, Shostakovich was called on to act as a Soviet propagandist, a role at which he was utterly unconvincing but which he was afraid to reject. It was not until 1958 that he was officially "politically rehabilitated" and more or less allowed to work under a bit less scrutiny.

According to Testimony, from his Fifth Symphony on, his major works often have double meanings: a "social realist" program, and hidden anti-Stalin messages. His use of Jewish themes was perhaps his clearest resistance in the anti-Semitic U.S.S.R.; his 13th Symphony, "Babi Yar," was censored for using a poem by Yevgeney Yevtushenko that dealt with a Nazi massacre of Russian Jews.

Shostakovich did write mediocre music constructed to please Soviet bureaucrats (mostly ballet suites and film scores), but when he was writing for himself, or surreptitiously against the authorities, his music speaks movingly of disillusionment and pessimism. ("The majority of my symphonies are tombstones," he is supposed to have stated.) The likelihood that his music showed secret resistance to Soviet authority has posthumously raised his reputation in the West.

Whatever the programmatic elements of his music, Shostakovich's work can stand on its own merits apart from political programs. His 15 Symphonies are arguably the greatest such cycle since Mahler (whose influence is clear); cumulatively his 15 String Quartets are the supreme achievement in that format since Beethoven's. His concertos have become repertoire favorites, at least by the standards of 20th century fare. Now, a look at his most important work.

Symphonies

For a few years, the choice was easy. Rudolf Barshai, a longtime collaborator with Shostakovich and an excellent conductor, recorded a generally fine and often brilliant set of the fifteen symphonies that was reissued at an ultra-bargain price by Brilliant Classics. That seems to have gone out of print, although it may still be available as an import (though not nearly as cheaply as before). One of its benefits is that the lesser works in the cycle -- Symphonies Nos. 2-3 and 12 -- get unusually persuasive readings. He's exceptionally good, even great, in some of the masterpieces as well, with the Fifth taut, the Sixth nearly definitive, the Eighth profoundly intense, the Ninth capturing its subversiveness, the Tenth powerfully dramatic, the Eleventh aptly tragic, the Thirteenth ("Babi Yar") arguably the best and certainly the most soul-shaking recording ever, the Fourteenth (which Barshai premiered) highly perceptive in interpretation and deeply nerve-wracking. In the Seventh ("Leningrad") and the Fifteenth, Barshai offers streamlined alternatives to the top recommendations, downplaying the sarcastic bombast of the former (for those who find its apparently deliberately tasteless "invasion" sequence too over-the-top) and favoring humor rather than morbidity in the latter. There's a new complete SACD set on Capriccio led by Dmitri Kitaenko that's got somewhat superior sonics and competitive interpretations, though overall I still prefer Barshai. Either way, it's worth looking at key performances of the cycle's best works.

For a few years, the choice was easy. Rudolf Barshai, a longtime collaborator with Shostakovich and an excellent conductor, recorded a generally fine and often brilliant set of the fifteen symphonies that was reissued at an ultra-bargain price by Brilliant Classics. That seems to have gone out of print, although it may still be available as an import (though not nearly as cheaply as before). One of its benefits is that the lesser works in the cycle -- Symphonies Nos. 2-3 and 12 -- get unusually persuasive readings. He's exceptionally good, even great, in some of the masterpieces as well, with the Fifth taut, the Sixth nearly definitive, the Eighth profoundly intense, the Ninth capturing its subversiveness, the Tenth powerfully dramatic, the Eleventh aptly tragic, the Thirteenth ("Babi Yar") arguably the best and certainly the most soul-shaking recording ever, the Fourteenth (which Barshai premiered) highly perceptive in interpretation and deeply nerve-wracking. In the Seventh ("Leningrad") and the Fifteenth, Barshai offers streamlined alternatives to the top recommendations, downplaying the sarcastic bombast of the former (for those who find its apparently deliberately tasteless "invasion" sequence too over-the-top) and favoring humor rather than morbidity in the latter. There's a new complete SACD set on Capriccio led by Dmitri Kitaenko that's got somewhat superior sonics and competitive interpretations, though overall I still prefer Barshai. Either way, it's worth looking at key performances of the cycle's best works.

Symphony No. 1 in F minor, Op. 10 The First, however youthful, is a mature and deeply affecting work that ranks in the pantheon of the great symphonies. It's witty in the fast movements, heartbreaking in the slow ones -- a tendency Shostakovich often showed later as well. Leonard Bernstein's first recording (with the New York Philharmonic) is still the best, but -- like way too much Sony stuff lately -- it's out of print, though presumably it will reappear. (His later recording with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, on Deutsche Grammophon, coupled with a spectacular Seventh, is a bit hysterical to be entirely apt for this early work.) Leopold Stokowski was a dedicated advocate of Shostakovich's symphonic work throughout his career, and conducted the American premiere of the First Symphony (as well as the Sixth, Eleventh, and Twelfth). The sonics of his 1933 recording (a 1958 Capitol recording in much finer sound is now unavailable) with the Philadelphia Orchestra are not up to modern standards, but it's easy to hear what a superb performance it is. It comes in a two-CD set on Pearl with equally recommendable versions of the Fifth and Seventh. Many listeners will prefer the classic 1959 Eugene Ormandy recording with the Philadelphia Orchestra, just reissued by Sony/BMG and coupled with a must-have First Cello Concerto (see below). The intensity is lower than with Stokowski, but the Philadelphians play beautifully and the sound is pretty much perfect.

Symphony No. 4 in C minor, Op. 43 Shostakovich's most daringly modern symphony in sound and construction, it sat in a drawer for 25 years after he decided it was suicidally similar to the opera that offended Stalin; the premiere came in 1961. There used to be an excellent Columbia two-fer of Ormandy/Philadelphia in the Fourth (in 1963) and the Tenth; here's hoping it reappears soon. There's a thrilling Mstislav Rostropovich rendition (National Symphony Orchestra, far superior to his London recording), but only available in an uneven and expensive Teldec box set. Fortunately, this is one of the few Barshai performances available separately (on Regis) from his box set, and at a bargain price to boot.

Symphony No. 5 in D major, Op. 47 Shostakovich "rehabilitated" himself in 1937 with his Fifth, and it's long been the most popular of his symphonies; the Largo is one of his most heartrendingly beautiful slow movements. The bombastic finale, his appeasement of the cultural commissars, contains grinding dissonances that slip by in faster tempos, so some Russian conductors like to take it slowly to emphasize these, but Shostakovich specifically praised Bernstein's manic 1959 recording with the New York Philharmonic. That's available on two issues, one coupled with Bernstein's also-recommendable reading of the neo-Classical-flavored "merry" Ninth, the other instead augmented by Barshai's recording of his own arrangement for string orchestra of Shostakovich's gut-wrenching String Quartet No. 8 (retitled Chamber Symphony, Op. 83a). Bernstein made an even better (and better-sounding) recording of the Fifth twenty years later, a little slower and more piquant; it's coupled with an excellent Cello Concerto No. 1 (see below). I believe that no maestro has ever bettered Stokowski's 1939 performance (Pearl) in terms of balancing emotional drama and coherence, and the sound is superior to most records of that era, so relatively little orchestral detail is lost. The strings in I and III -- two of Shostakovich's most heartrendingly beautiful slow movements -- are lushly ravishing, and the winds and brass are sprightly and characterful in II and IV. Above all, Stokowski balances the piece's contrasting moods vividly and perfectly contours the phrasing.

Symphony No. 5 in D major, Op. 47 Shostakovich "rehabilitated" himself in 1937 with his Fifth, and it's long been the most popular of his symphonies; the Largo is one of his most heartrendingly beautiful slow movements. The bombastic finale, his appeasement of the cultural commissars, contains grinding dissonances that slip by in faster tempos, so some Russian conductors like to take it slowly to emphasize these, but Shostakovich specifically praised Bernstein's manic 1959 recording with the New York Philharmonic. That's available on two issues, one coupled with Bernstein's also-recommendable reading of the neo-Classical-flavored "merry" Ninth, the other instead augmented by Barshai's recording of his own arrangement for string orchestra of Shostakovich's gut-wrenching String Quartet No. 8 (retitled Chamber Symphony, Op. 83a). Bernstein made an even better (and better-sounding) recording of the Fifth twenty years later, a little slower and more piquant; it's coupled with an excellent Cello Concerto No. 1 (see below). I believe that no maestro has ever bettered Stokowski's 1939 performance (Pearl) in terms of balancing emotional drama and coherence, and the sound is superior to most records of that era, so relatively little orchestral detail is lost. The strings in I and III -- two of Shostakovich's most heartrendingly beautiful slow movements -- are lushly ravishing, and the winds and brass are sprightly and characterful in II and IV. Above all, Stokowski balances the piece's contrasting moods vividly and perfectly contours the phrasing.

Symphony No. 7, Op. 60 "Leningrad" The controversial Seventh was begun in July 1941, after Hitler invaded the U.S.S.R. The Nazi army soon besieged Leningrad for 900 days; about a million people died, a third of the city's population. Testimony says it depicts "the Leningrad that Stalin destroyed and that Hitler merely finished off." It's also musically controversial; in the first movement, a deliberately banal theme (how Mahleresque) interrupts the normal sonata form to graphically embody the Nazi invasion. The other three movements are heart-wrenching. Leading the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, supreme Mahlerite Bernstein imbues the Seventh with the fullest measures of his great emotive power in a brooding live recording on a two-CD set that's pricey but well worth the expense (his earlier NYPO recording of the Seventh, on Columbia/Sony, has 40 bars cut from the first movement and thus can't earn a whole-hearted recommendation in spite of its good points.) Stokowski's 1942 recording of the Seventh, with the NBC Symphony Orchestra, was made in the notoriously dry acoustics of NBC Studio 8-H (nor does it appear that Pearl had especially clean disks for its transfer). Arturo Toscanini and Stokowski -- then sharing conducting duties at NBC -- competed bitterly for the first American performance of the Seventh. Toscanini in later years expressed an aversion to the piece, but at the time it was an important symbol for the devoutly anti-Fascist Italian conductor: Shostakovich supposedly disliked Toscanini's exciting but ultimately one-dimensional reading (formerly on RCA, but not worth searching for). Stokowski's version is much more full-blooded, and collectors not averse to period sonics need to hear it.

Symphony No. 7, Op. 60 "Leningrad" The controversial Seventh was begun in July 1941, after Hitler invaded the U.S.S.R. The Nazi army soon besieged Leningrad for 900 days; about a million people died, a third of the city's population. Testimony says it depicts "the Leningrad that Stalin destroyed and that Hitler merely finished off." It's also musically controversial; in the first movement, a deliberately banal theme (how Mahleresque) interrupts the normal sonata form to graphically embody the Nazi invasion. The other three movements are heart-wrenching. Leading the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, supreme Mahlerite Bernstein imbues the Seventh with the fullest measures of his great emotive power in a brooding live recording on a two-CD set that's pricey but well worth the expense (his earlier NYPO recording of the Seventh, on Columbia/Sony, has 40 bars cut from the first movement and thus can't earn a whole-hearted recommendation in spite of its good points.) Stokowski's 1942 recording of the Seventh, with the NBC Symphony Orchestra, was made in the notoriously dry acoustics of NBC Studio 8-H (nor does it appear that Pearl had especially clean disks for its transfer). Arturo Toscanini and Stokowski -- then sharing conducting duties at NBC -- competed bitterly for the first American performance of the Seventh. Toscanini in later years expressed an aversion to the piece, but at the time it was an important symbol for the devoutly anti-Fascist Italian conductor: Shostakovich supposedly disliked Toscanini's exciting but ultimately one-dimensional reading (formerly on RCA, but not worth searching for). Stokowski's version is much more full-blooded, and collectors not averse to period sonics need to hear it.

Symphony No. 8 in C minor, Op. 65 From the Fifth on, Yevgeny Mravinsky led the premieres of most of Shostakovich's Symphonies. The desolate five-movement Eighth of 1943, mournful and monumental, is dedicated to him. One of Mravinsky's finest talents was making massive, potentially unwieldy structures cohere, a must in this work which opens with a nearly half-hour movement as tortured and intense as any by Mahler. His historic 1947 Melodiya recording is out of print, but a fiery 1960 concert recording released by the BBC's label is in better sound, of course, and absolutely earth-shattering in its emotional impact. As usual, he leads the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra. (Avoid an out-of-print 1982 recording that Philips mastered a half-step too high.) Andre Previn made two fine recordings with the London Symphony Orchestra, first for Angel (later EMI) in 1973, then for Deutsche Grammophon in 1992, but both are now gone -- too bad, both had excellent sonics.

Symphony No. 10 in E minor, Op. 93 The Tenth is perhaps Shostakovich's most formally satisfying symphony; written immediately after Stalin's 1953 death, its Allegro is said -- by no less an authority than Shostakovich's son Maxim -- to portray Stalin. The Ormandy (Columbia) is still the best. Why does he not get the respect of other conductors at his level? Maybe because he didn't care about image, just about music. Mravinsky's reading is also great but in a more forceful manner, emphasizing the pain in the music. His 1976 concert recording on Erato with the Leningrad Philharmonic, which he ruled for decades, is the most intense. The 1966 recording by Herbert von Karajan, who recorded none of the other symphonies but essayed this one twice, is also excellent. It's on Deutsche Grammophon, which also has a 1981 digital version that doesn't sound as good and isn't as exciting.

Symphony No. 11 in G minor, Op. 103 "The Year 1905" Another highly programmatic work that operates on two levels. In 1957, Shostakovich and his fellow composers were expected to commemorate the fortieth anniversary of the Revolution. He'd already been there, done that with his Second Symphony, "To October." instead, he depicted the 1905 massacre of a crowd by Czar Nicholas's palace guards. He did so soon after Soviet tanks had crushed the liberal regime in Budapest and hard-liners had been installed to keep Hungary in line with the U.S.S.R., so of course there's a double meaning: on the surface, sentiments the authorities couldn't criticize, but under that an implicit accusation. For a long time the Stokowski with the Houston Symphony Orchestra (Capitol/EMI), overflowing with drama and emotion, was the #1 choice. In 1996 Valery Polyansky with the Russian State Symphony on Chandos stretched every movement to excrutiating lengths (he takes 73:57 compared to Stokowski's 62:38, already on the longer end of the spectrum) and wrung every ounce of emotion from it in an absolutely devastating rendition. Some may find Polyansky too over-the-top, though, and want to stick with Stokowski.

Symphony No. 13 "Babi Yar" Shostakovich stirred up more trouble with this work, which uses poems by Yevgeny Yevtushenko, including "Babi Yar," addressing a Nazi massacre of Jews and the way the government had basically ignored it because of anti-Semitism. It caused a stir, and eventually the authorities required textual changes to soften the accusation. Barshai's rendition is available separately on Regis and features an excellent Russian bass, Sergei Alexashkin. Kurt Masur's stirring performance with the New York Philharmonic and Sergei Leiferkus (Teldec) comes with Yevtushenko reading "Babi Yar" and "The Loss."

Symphony No. 15, Op. 141 Shostakovich's last symphony presents difficult questions of interpretation too complex to go into here, though interested readers can read my in-depth review here. This can easily be seen as a dark and bitter work, yet Shostakovich's music is never merely depressed; there are always touches of sardonic humor. Early performances by Russian conductors either played down the darkest moments (Mravinsky, 1976 concert on Melodiya and Olympia) or emphasized the sardonic aspects (Kiril Kondrashin, Moscow Philharmonic, 1974 on Icone). Another early reading is Ormandy's (he gave the U.S. premiere), which sounds great and balances the different aspects of the score well. (On RCA, it's coupled with an unbeatable Emil Gilels rendition of the Piano Sonata No. 2.) The Bernard Haitink/London Philharmonic Orchestra recording is commendable both for excellent sound and for much more expansive slow movements; altogether, it lasts 45 minutes and 39 seconds (the score suggests a duration of "approximately 48 minutes") as opposed to the much quicker Mravinsky (39:31) and Kondrashin (40:11). It includes an equally fine reading of the devastating song cycle From Jewish Folk Poetry with soloists Elisabeth Soderstrom (soprano), Ortrun Wenkel (contralto), and Ryszard Karczykowski (tenor). But for the most emotionality, Kurt Sanderling's second recording (1991, Erato) is the one to get -- plus the Cleveland Orchestra sounds wonderful.

Symphony No. 15, Op. 141 Shostakovich's last symphony presents difficult questions of interpretation too complex to go into here, though interested readers can read my in-depth review here. This can easily be seen as a dark and bitter work, yet Shostakovich's music is never merely depressed; there are always touches of sardonic humor. Early performances by Russian conductors either played down the darkest moments (Mravinsky, 1976 concert on Melodiya and Olympia) or emphasized the sardonic aspects (Kiril Kondrashin, Moscow Philharmonic, 1974 on Icone). Another early reading is Ormandy's (he gave the U.S. premiere), which sounds great and balances the different aspects of the score well. (On RCA, it's coupled with an unbeatable Emil Gilels rendition of the Piano Sonata No. 2.) The Bernard Haitink/London Philharmonic Orchestra recording is commendable both for excellent sound and for much more expansive slow movements; altogether, it lasts 45 minutes and 39 seconds (the score suggests a duration of "approximately 48 minutes") as opposed to the much quicker Mravinsky (39:31) and Kondrashin (40:11). It includes an equally fine reading of the devastating song cycle From Jewish Folk Poetry with soloists Elisabeth Soderstrom (soprano), Ortrun Wenkel (contralto), and Ryszard Karczykowski (tenor). But for the most emotionality, Kurt Sanderling's second recording (1991, Erato) is the one to get -- plus the Cleveland Orchestra sounds wonderful.

Concertos

In all three cases, the first concerto Shostakovich wrote for an instrument is more popular than its successors. There's a Columbia disc that combines the premiere recordings of two of them. The Violin Concerto No. 1 in A minor, Op. 77 (99)was another "drawer" work, finished in 1948 but saved until 1955 (resulting in dual opus numbers) for publication and performance. Dedicated to David Oistrakh, who premiered it, it's a real virtuoso showcase and stands out sonically for its omission of trumpets and trombones. He's accompanied superbly here by the New York Philharmonic led by Dimitri Mitropoulos. The Concerto for Cello & Orchestra No. 1 in E-flat major, Op. 107 is another dazzler, thanks especially to its massive written-out cadenza. It was written in 1959 for dedicatee Mstislav Rostropovich, who amazingly learned the solo part in just four days. Ormandy and the Philadelphians support him in fine style. Both the performances on this CD were taped in the U.S. in the late 1950s, when a certain amount of cultural exchange had begun. The second concertos shouldn't be forgotten just because they are less ingratiating. Oistrakh's best version of the Violin Concerto No. 2, Op. 129, was the premiere recording with Kondrashin that used to be available on a two-CD RCA Red Seal Artists of the Century set, The Essential David Oistrakh, that also included a thrilling First Concerto with Mravinsky accompanying. (Could this label please be less cavalier about keeping its treasures available to the public?) Fortunately, a concert reading with Yevgeny Svetlanov and the USSR State Symphony Orchestra on the BBC's label, also paired with the First (with Gennady Rozhdestvensky and the Philharmonia Orchestra), picks up the slack, though it's an iota less precise and exciting. And the 1990s recordings by Maxim Vengerov must also be heard for their superhuman energy. They come on separate Teldec discs, each paired with the Prokofiev concerto of the same number. Mstislav Rostropovich conducts the London Symphony Orchestra, or perhaps it would be more accurate to say he leads them along the same razor's edge that Vengerov is walking!

It's inevitable that just as Oistrakh dominates the Violin Concertos that were written for him, Rostropovich dominates the Cello Concertos composed with him in mind. His best reading of No. 2, Op. 126 came with Seiji Ozawa and the Boston Symphony Orchestra, now available on a two-CD Deutsche Grammophon set. There is also a cheap two-CD EMI set on which Rostropovich plays both concertos, with Gennady Rozhdestvensky leading the Moscow Philharmonic in the First and Yevgeny Svetlanov the USSR State Symphony Orchestra in the Second. There has so far been no Vengerov of the cello to seriously challenge Rostropovich's supremacy in these pieces.

Shostakovich was a pianist himself, and though the gloomy works are taken most seriously, he also wrote effervescent music as witty as Poulenc's; his two concertos with piano (the one adding trumpet is really No. 1) display this side of his personality. Pianists more assured than the composer have recorded them, but he did get a diploma of honor in the 1926 International Chopin Competition. His 1958 readings, now in EMI's Great Recordings of the Century series, have unsurpassed vitality and soul. The solo piano passage in the fourth movement of the First Concerto at times seem rather hectic, but the notes are all there and the effect is somehow appropriate. Trumpeter Ludovic Vaillant's vibrant tone is practically echt-Russian. Andre Cluytens leads the French National Radio Orchestra. There is more of the composer's dark humor in these performances than in any others. Some solo pieces, especially five Preludes & Fugues (despite some gabbled contrapuntal passages), are valuable filler. I also recommend Bernstein's effervescent performances of the concertos, but guess what? You'll have to look for them used. Yefim Bronfman's set with the Los Angeles Philharmonic under Esa-Pekka Salonen (Sony) is also excellent and offers fine sonics. For the most high-energy First, Martha Argerich is dazzling with trumpeter Guy Touvron and Jorg Faerber leading the Wurttemberg Chamber Orchestra Heilbronn on Deutsche Grammophon.

Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk

Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk

Ironically, the work that caused Shostakovich the most trouble was a massive success at first, hailed as a "triumph of Soviet musical theatre" and a "giant step toward Socialist Realism." Its very success led Stalin to attend a performance, where the dictator was offended by the eroticism of the story (famously, a sex scene is accompanied by lascivious trombone glissandos) and the extreme dissonances in the harmonies, leading directly to the infamous Pravda denunciation. Unheard for years, it now lives on the fringe of the repertoire, still shocking to conservative audiences. This classic performance led by Rostropovich (EMI) features soprano Galina Vishnevskaya and bass Nicolai Gedda, two of the greatest Russian singers of the second half of the 20th century. Rostropovich was a student of Shostakovich and became friend and collaborator. When Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk was allowed to be revived in the 1960s, culminating in a film, Rostropovich led the cello section, and his wife, Vishnevskaya, sang the title role. Valuable experience with the composer leading, but Shostakovich had felt obliged to revise the work. Rostropovich says Shostakovich asked him to use the original 1932 score if he ever recorded it, and Rostropovich found a copy of this lost score in, surprisingly, the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. One month before this set was recorded in April 1978, Rostropovich and Vishnevskaya had their Soviet citizenships revoked. This stunning two-CD set oozes sarcasm, fury, black humor, and even deeply touching beauty, but always emotional intensity. Vishnevskaya's indelibly etched performance as Katerina Ismailov is the focus, and she earns all of the many kudos this performance has garnered, but the entire cast is inspired.

String Quartets It has often been noted that, where the Symphonies were Shostakovich's public face, the String Quartets -- also 15 in number -- were his private expression. Partly this of course is inherent in the genre, but in his case it's also because the bureaucracy paid relatively little attention to chamber music, giving him much greater latitude for self-expression. No quartet cycle of the 20th century matches Shostakovich's 15 in sheer nerve-wracking impact, emotional breadth, and imaginative variety, not to mention debatable subtexts and hidden meanings. The angst-ridden Eighth is the boldest scream of anguish and anger, while the Fifteenth is a stunning, numbing acceptance of oncoming death, bereft of hope. The Borodin Quartet's classic second cycle (for Melodiya, the Soviet state label) is overwhelming in its outpouring of emotion, and includes the Piano Quintet with Sviatoslav Richter. Unhappily, both this set as reissued by BMG and their earlier, incomplete cycle of 1 through 13 (because the last two hadn't been written yet) reissued by Chandos have both disappeared again. Nor is the Beethoven Quartet, which premiered many of the quartets and worked closely with the composer, currently represented in the racks, though there is a reissue scheduled for November. But not only is the Emerson Quartet's 2000 cycle on Deutsche Grammophon available, it was repackaged earlier this year in a bargain box that goes for under $40 for five CDs. The Emerson's intense, energetic survey of the cycle was recorded in concert at the Aspen Music Festival in 1994 and '98-99. Intonation, blend, and balance are impeccable; this is the lean, knife-like alternative (similar to the Beethoven Quartet) to the Borodin's more expansive approach. The sonics are as good as studio sound, but the "live" playing carries an extra edge that's undeniable.

Sonata for Cello & Piano, Op. 40; Sonata for Violin & Piano, Op. 134; Trio for Violin, Cello & Piano, Op. 67 Shostakovich's chamber music is intimate and highly personal, aspects highlighted by this remarkable Eclectra collection on which the composer plays the piano parts. The 1968 Violin Sonata was recorded that year at Oistrakh's Moscow apartment. The Cello Sonata with Daniil Shafran comes from a 1946 Melodiya session, while the Piano Trio with Oistrakh and cellist Milos Sadlo dates from 1947 for Supraphon. Sound on all three items is remarkably good under the circumstances, and the performances are stunning.

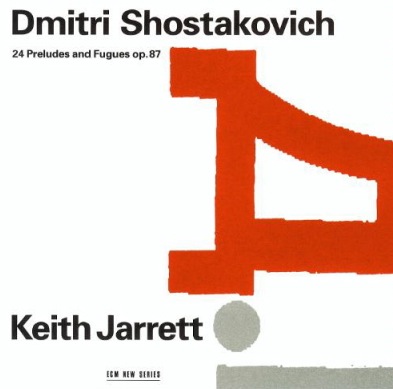

24 Preludes & Fugues for Piano, Op. 87 This intimate, abstract 1950-51 cycle was inspired in the bicentennial of Bach's death by the example of the Well-Tempered Clavier. It's in stark contrast to his usual modes of writing, and as played with tonal sheen and digital dexterity by Jarrett, quite beautiful. Keith Jarrett's 1992 recording (ECM) is much easier on the ears than the dour, labored recordings by the cycle's dedicatee, Tatiana Nikolaeva (first Melodiya, then Hyperion). Though Jarrett's playing is polished and generally moves at a quicker pace than either Nikolaeva or Vladimir Ashkenazy, darker works -- for instance, No. 14 -- are given their just weight and mysteriousness. If his reading abjures overwhelming Russian angst, that seems reasonable and fittingly Bachian; if you want the angst, get Ashkenazy (Decca). Jarrett also has the best sound of the three. Choosing Jarrett in this music is a minority opinion, probably because he's -- gasp -- an American jazz musician rather than Russian, but hey, Shostakovich liked jazz.

24 Preludes & Fugues for Piano, Op. 87 This intimate, abstract 1950-51 cycle was inspired in the bicentennial of Bach's death by the example of the Well-Tempered Clavier. It's in stark contrast to his usual modes of writing, and as played with tonal sheen and digital dexterity by Jarrett, quite beautiful. Keith Jarrett's 1992 recording (ECM) is much easier on the ears than the dour, labored recordings by the cycle's dedicatee, Tatiana Nikolaeva (first Melodiya, then Hyperion). Though Jarrett's playing is polished and generally moves at a quicker pace than either Nikolaeva or Vladimir Ashkenazy, darker works -- for instance, No. 14 -- are given their just weight and mysteriousness. If his reading abjures overwhelming Russian angst, that seems reasonable and fittingly Bachian; if you want the angst, get Ashkenazy (Decca). Jarrett also has the best sound of the three. Choosing Jarrett in this music is a minority opinion, probably because he's -- gasp -- an American jazz musician rather than Russian, but hey, Shostakovich liked jazz.