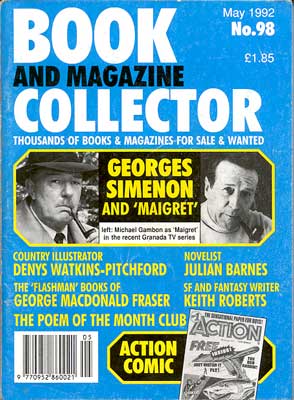

The Belgian-born Georges Simenon (1903-1989) was a literary phenomenon of the 20th century, giving Balzac a run for his money, at least in terms of output. According to Wikipedia, he wrote over 200 novels plus many shorter works. The New York Times estimates that number (including his memoirs and nonfiction works) as being between 400 and 500. Not unexpectedly then, Simenon is considered by some to be the most successful author of the 20th century, and his creation, Inspector Jules Maigret, who appeared in about 75 works, "ranks only after Sherlock Holmes as the world's best known fictional detective." (I'm not sure how Poirot feels about that.) In preparation for viewing and reviewing six of the celluloid offerings in the series Cine-Simenon: George Simenon on Film, presented by Anthology Archives with Kathy Geritz and the Pacific Film Archive, I nestled down with the textural Simenon, and within a week, I had plowed through five of his works, four featuring Maigret. An addiction had been born.

In No Vacation, Maigret escapes Paris, his home base, for a few weeks in Les Sables d'Olonne when his wife immediately has an appendicitis attack. While he's visiting Madame in the hospital, a nun slips a note into his pocket urging him to chat with the girl in Room 15, who "accidentally" fell out of her brother-in-law's car while on the way to a dance concert. Before Maigret can do so, the young woman dies -- or was she murdered? And who's next? And can the brother-in-law, a doctor and one of the most respected citizens of this small resort town, be culpable? Vivisecting both cultural and economic prejudices, while side-slapping nuns and the press a bit, here's a truly pleasant crime novel.

Inspector Cadaver (1944) follows along in a similar vein. Maigret, now as a favor, unofficially travels to the provincial town of Saint-Aubin-les-Marais to decimate the rumors that his friend's brother-in-law, Etienne Naul, the richest man in the locale, had anything to do with the untimely death of a young man fatally run over by a train late one evening. But to his uneasy surprise, Maigret finds that Naul, his wife, the victim's mother, and most of the residents want the crime specialist to depart as rapidly as he arrived. Leave well enough alone, Monsieur. Of course, Maigret cannot. Once again finances play a role in how much justice a populace actually deems appropriate for the loss of a life.

Maigret and the Killer (1969) plays off Simenon's prime strength, besides his capability to instantly hook in a reader. Few writers, indeed, have his ability to lay open the psychology of a soul that murders not for personal gain but to fulfill some emotional vacancy. Here a hippyish "tall, thin fellow in a suede jacket," with one of those huge tape recorders on a strap around his neck, is stabbed seven times in the back in front of witnesses on a rainy Parisian night. He's heir to a mega perfume fortune. Is there a connection to his dad's eau de toilette? Or did he accidentally record a crime on his recorder? Or...? The culprit here could give Norman Bates a run for his money.

In the latter work, take a moment to note how the everyday Frenchman constantly reflects on every gent having long hair. Besides Simenon concocting a delicious crime or two or three in each of his tomes, he also captures the charms and prejudices of each of the five decades in which Maigret is trying snare his killer(s).

Maigret and the Madwoman (1970) renders Maigret at his most guilt-ridden. A highly ingratiating, elderly lady arrives at his office and complains, "At least four times in the past two weeks, I've noticed that my things have been moved."

"What do you mean? Are you saying that after you've been out, you've come back to find your things disturbed?"

"That's right. A frame hanging slightly crooked or a vase turned around. That sort of thing."

"Are you quite sure?"

"There you are, you see! Because I'm an old woman, you think I'm wandering in my wits. I did tell you, don't forget, that I've lived forty-two years in that same apartment. Naturally, if anything is out of place, I spot it at once."

But nothing has been stolen, so what are the police to do? Not much until this pleasant oldster is strangled to death. Expect a pimp, a manly masseuse, two dead husbands, a musician, plus a crime boss or two to get involved before Maigret can solve this one.

But many of Simenon's novels are not crime-ridden, and the majority lack his loveable commissaire. A classic example, and apparently his last effort in the non-crime milieu, is the superb The Innocents, one of the best portraits of a marriage you'll venture across. (It might be mentioned here that while Simenon was wed several times, he was a constant adulterer, often with the live-in help, and he claims to have bedded over 10,000 women, many of them prostitutes.)

The hero here is Monsieuer Georges Celerin, an exceedingly happy man. He's been blissfully married for 20 years, he has two delightful children and a perfect live-in maid, and is a co-owner of a distinguished jewelry concern that is acclaimed for the designs he himself creates.

Then on page seven, a policeman comes to his office and announces, after touching his cap, "I'm sorry, Monsiuer Celerin, I have bad news for you. You are, are you not, the husband of Annette-Marie Stephanie Celerin?"

"That is my wife's name, yes."

"She has met with an accident."

"What sort of accident?"

"She was run over by a truck on Rue Washington...."

"Is it serious?'

"She was dead on arrival at the hospital -- the Lariboisiere."

"Annette? Dead?"

Suddenly, Celerin's life is put into a tailspin. During bouts of extreme mourning, he realizes his wife was everything to him, she and his job. Even his children were secondary. But as he starts going over his past memories, he begins to realize there is another way to recall each of those events.

Reminiscing about the early days of his honeymoon and marriage, Celerin realizes he "had been happy. He had been full of his own happiness. From now on he would be living with her. He would see her every day, at breakfast, lunch, and dinner, and he would be sleeping next to her at night.

"That same evening, they had taken the Blue Train to Nice. His happiness had persisted. He was living in a dream, in spite of his wife's frigidity."

Maybe he and Annette hadn't been the ideal couple. Maybe when there were tears in her eyes while they were making love, those weren't droplets of gratitude. And what was she, a social worker, doing in a rather wealthy neighborhood in the middle of the day when she fatally slipped in front of that truck?

Brick by brick, his past two euphoric decades are dismantled, and Celerin slowly gets to know the woman he loved far too late. Yes, there is a mystery of sorts here, but the type of mystery many of us have to confront daily. Do we actually know the people we are smitten with or are we examining the world in a way that alters reality?