Maria Lassnig

"Man is the measure of all things: of things which are, that they are, and of things which are not, that they are not." Protagoras, quoted in Plato's Theaetetus

"Both the motor and sensory homunculi usually appear as a small man superimposed over the top of the precentral or postcentral gyrus, for motor and sensory, respectively. The homunculus is oriented with feet medial and shoulders lateral on top of both the precentral and the postcentral gyrus (for both motor and sensory). The man's head is depicted upside down in relation to the rest of the body such that the forehead is closest to the shoulders. The lips, hands, feet and sex organs have more sensory neurons than other parts of the body, so the homunculus has correspondingly large lips, hands, feet, and genitals. The motor homunculus is very similar to the sensory homunculus, but differs in several ways. Specifically, the motor homunculus has a portion for the tongue most lateral while the sensory homunculus has an area for genitalia most medial and an area for visceral organs most lateral. Well known in the field of neurology, this is also commonly called 'the little man inside the brain.' This scientific model is known as the cortical homunculus." Cambridge University Dictionary of Medical Diagnostics (Dr. Philip Kennedy, Editor, 2013 edition)

"I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking…some day, all this will have to be developed, carefully printed, fixed." Christopher Isherwood

Despite your best efforts and beliefs to the contrary, your life is a series of random events and experiences; you are merely in different rooms, at different times, in different places, with different people. Things around you are in a state of change—you are the only constant. John Updike wrote, “We walk through volumes of the unexpressed and like snails leave behind a faint thread excreted out of ourselves.” Maria Lassnig is someone who understands that these lipstick traces, tiny gestures, and human stains are of the utmost importance—the way we document our existence. For seven decades she has attempted to reconcile existential frailty and paint, creating a body of work that is both innovative in philosophy and style, as her retrospective at MoMA PS1 shows.

Lassnig was born in Carinthia, a rural Austrian state, in 1919, and attended the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna during the Second World War, a time when the Nazis had banned Expressionism as “degenerate” art and promoted a nationalistic form of social realism. Partly in reaction to this, and due to “[a desire] to go beyond skill, beyond the security of the real, into uncharted territory,” Lassnig developed an expressive form of self-portraiture she termed the “body awareness technique.” Drawing from time spent in Paris in the 1950s, where she met André Breton and absorbed elements of surrealism, automatic writing and painting, and existentialist philosophy, Lassnig returned to Austria and embarked on that voyage into “uncharted territory.” She created a series of abstract portraits; exteriorizing their interiority, they were stripped of their most identifiable physiognomic features of eyes, nose, and mouth. Executed with palette knives instead of brushes, (for example, Head, 1956), the paintings become assemblages of material created with crude instruments, prefiguring Lassnig’s later interest in machinery and prosthetic devices in her work.

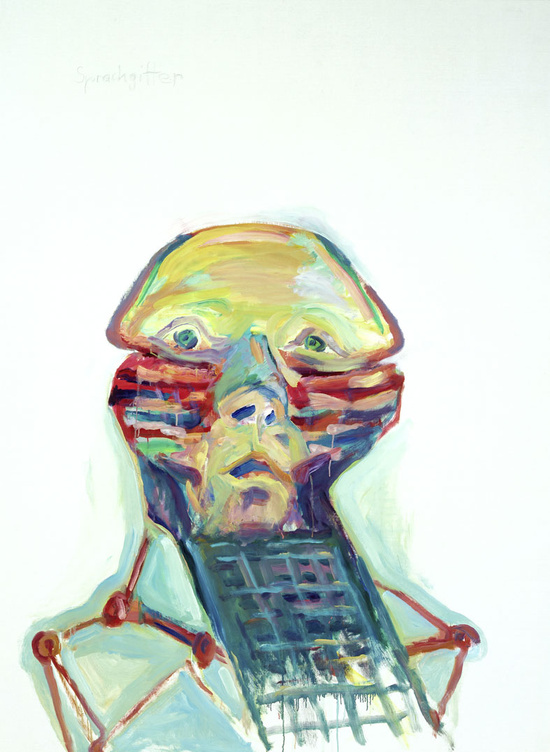

In her self-portraits, Lassnig’s fantasies and anxieties manifest themselves through a cast of mythical, monstrous, cyborg, and alien characteristics. The metaphoric use of technology in Language Grid (1999), with a head attached to a metal grate, sitting on an atomic structure of a body, gives us a rebus of imagery served as explanation of a personal, psychological state. She wrote, “I called my body awareness ‘paintings,’ then ‘introspective experiences’; later on I did not call them anything at all … I have only abandoned this ‘content’ when outside events were stronger than I was, when I encountered love…death…oppression.”

In her self-portraits, Lassnig’s fantasies and anxieties manifest themselves through a cast of mythical, monstrous, cyborg, and alien characteristics. The metaphoric use of technology in Language Grid (1999), with a head attached to a metal grate, sitting on an atomic structure of a body, gives us a rebus of imagery served as explanation of a personal, psychological state. She wrote, “I called my body awareness ‘paintings,’ then ‘introspective experiences’; later on I did not call them anything at all … I have only abandoned this ‘content’ when outside events were stronger than I was, when I encountered love…death…oppression.”

It would be difficult to categorize these paintings into distinct "periods" as with Picasso or de Kooning, because Lassnig’s painterly decades are not so much a development of style or concepts as they are snapshots of the artist at different ages, exploring differing notions about her "felt self." Her figures are like the motor sensory homunculus, a distorted view of her view of herself, yet one that feels more exacting through its skewness (untitled, 2002). Her figures usually have eyes and noses, with seeing and breathing being something one might be aware of while working, but as she aged and began to lose her hearing, Lassnig began to leave the ears off her portraits (Momento Mori, 2002).

In a work called Small Science Fiction Self-Portrait (1995), the earless and hairless artist peers through a rectangular screen, a prescient imagining of an Oculus Rift, with eyes wide shut. She melds imaginary technology in a metaphorical way -- this isn’t science fiction like Star Trek and Terminator as much as it is Black Mirror or Blade Runner. In a painting called Illusion of Missed Motherhood (1998), an alien fetus emerges from the artist -- a meditation on Lassnig’s choice to not have children, as well as the artist’s feelings of being excluded from her own artistic historical moment. In a note she made after watching the movie Alien, Lassnig said, “Only a woman and a cat survive the apocalypse.” Through a combination of vestigial appendages and phantom limbs, Lassnig creates a psychological modern Prometheus, Frankenstein’s monsters of the soul.

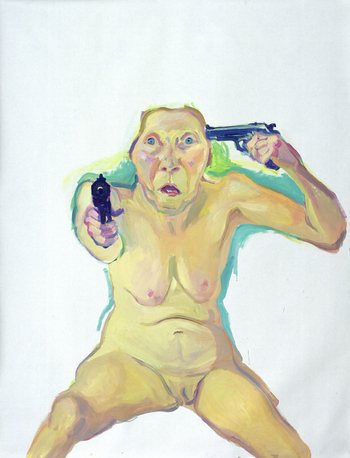

Lassnig lived in New York for nearly a decade, at first coming on an artist’s residency program, then living in the city during the height of anti-figurative and anti-painting conceptualism of the seventies, when she experimented with film (of particular note are Palmistry, 1974, and Shapes, 1972). This switch of medium might seem odd, considering the greater body of work her paintings comprise, but at her core Lassnig is a documentarian -- a realist in the tradition of Christopher Isherwood. She is both a camera and an x-ray machine. A later self-portrait, You or Me (2005), could be Lassnig’s version of Picasso’s Self-Portrait Facing Death (1972), the crayon and pencil nightmare of the artist looking in a mirror at his spent body. Pierre Daix said of his last visit to Picasso that he held the drawing up next to his head and that he did not blink. "I had the sudden impression that he was staring his own death in the face, like a good Spaniard." Lassnig, like Picasso, faces mortality head-on. In You or Me (2005) (image above), she confronts the viewer, naked (bald, flattened tits, shaved vulva) with two guns, one at her temple and one pointed to us, surrounded by an electric blue and green aura. It is a punk gesture, one of undisputed attitude. Juxtaposed against the sagging flesh of the artist, though, it is a measure of pure spirit. Lassnig shows an artist not going quietly into that good night, but one who will be leaving still kicking against the pricks.