"It's hard being a Jew nowadays," began my 2023 coverage of this annual fest. Well, it's still not a breeze, but not just for the Jews. Ask the Angelenos, the Ukrainians, the Yemenis, and the Palestinians whose plight is so shatteringly captured in the documentary No Other Land, screened at last year's New York Film Festival.

At the critics' screenings that September afternoon, an odd juxtaposition occurred. No Other Land was immediately followed by Jesse Eisenberg's nigh-perfect comedic drama, A Real Pain, which captures the lingering effect of the Holocaust on present-day Jews, a memory expiring far too swiftly. From the Middle East to Auschwitz within four hours, that's a handful.

Which got me thinking, can you compare pain? Or the memory of pain? The posthumously declared anti-Semite Joseph Campbell sidestepped the issue and advised: "Find a place inside where there's joy, and the joy will burn out the pain." Does that work against prejudice in the long run? Against genocide?

Maybe.

I do have a black-and-white snapshot of my stepmother smiling while sitting on a park bench in 1930s Berlin, a bench bearing a sign: "For Jews Only." She shortly escaped to the States but not before aborting what would have been her second child. Gerda Eisner Baum, as she was known then, refused to submit another soul to such a precarious future.

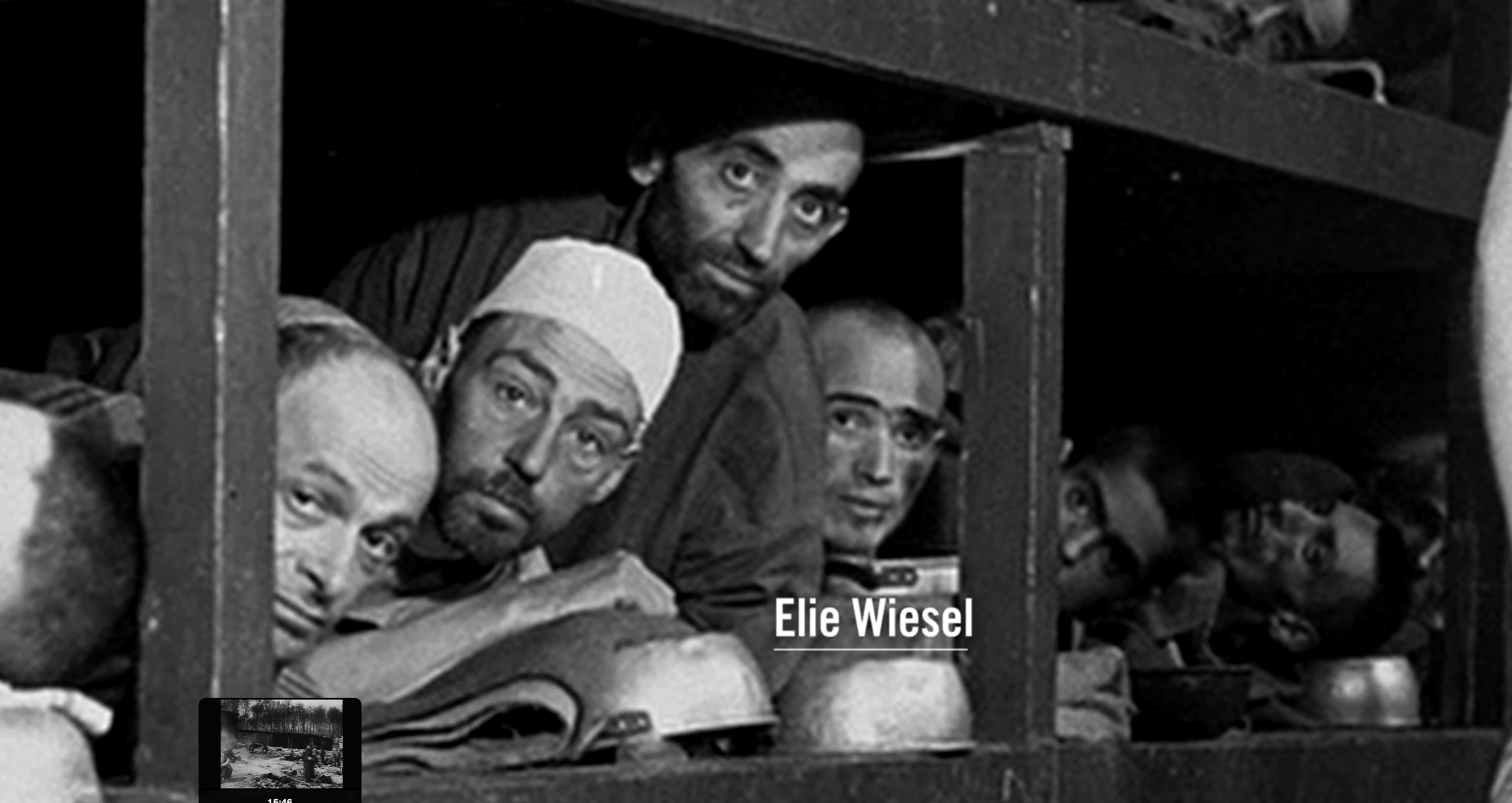

Our current future seems to be again approaching that sense of precariousness, and the 34th edition of the annual New York Jewish Film Festival perfectly captures that trembling-in-the-balance uneasiness through works of humor, nostalgia and tears. Works disclosing anti-Semitism past and present, interfaith coupling, and sectarian conflicts. [No wonder the author of Night, Elie Wiesel, once asked, "I'm a Jew, but I don't really know what it means to be Jewish."

Maybe the late Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, who was knighted by the Queen in 2005, best captures the gist of this year's NYJFF: "Jews have survived catastrophe after catastrophe in a way unparalleled by any other culture. In each case, they did more than survive. Every tragedy in Jewish history was followed by a new wave of creativity." Here, the creativity is on view.

Starting the Festival on a highly cheery note is Joe Stephenson's wry biopic of the man who discovered the Beatles, Midas Man, transforming them from a scraggly quartet playing in a Liverpudlian club for naught into the world’s most consequential band. Yes, Brian Epstein. He rose like a firework into the heavens for five years and then took permanent residence up there at age 32. Why?

John Lennon might have been recalling Brian when he put forth: "The basic thing nobody asks is why do people take drugs of any sort? Why do we have these accessories to normal living to live? I mean, is there something wrong with society that's making us so pressurized, that we cannot live without guarding ourselves against it?"

Well, Brian was both a Jew and a homosexual in a country that rewarded both with an outsider status. Queerdom could also get you arrested, beaten, and blackmailed, but for some, the double whammy might also spur you on to succeed at any cost, as it did with the gent who gave us Help (1965).

Midas Man commences with the future entrepreneur working out of his father’s furniture store where he created within several square yards the hippest, most successful record store in Liverpool.

One day several customers requested "My Bonnie," a recording from a small German company by an unknown band. "What's this?" Brian wondered. Discovering the group was a local one, he sought out the lads, became their manager, replaced their drummer with Ringo, and after being rejected by Decca and a gaggle of other record companies, he got the Beatles a record deal. "I Want to Hold Your Hand" became their first number one hit, and the rest is part of our history.

Yes, those executives who laughed when Brian insisted, "My boys will be bigger than Elvis," laughed no more. Without this tortured Jewish homosexual, there might not have been a British Invasion, and we’d still be listening to Perry Como.

With a vivid recreation of all this hoopla, the superb Jacob Fortune-Lloyd as Brian, Emily Watson as Mom, Jay Leno as Ed Sullivan, and four lookalike, often sardonic Beatles, Midas Man is a never-less-than-engaging look at not totally surviving the sixties, a perfect Brit counterpart to A Complete Unknown.

Moving on to the more disquieting, writer/director Oren Rudavsky's devastating, necessary documentary, Elie Wiesel: Soul on Fire, concerns being a witness to history and then disseminating the horrors that the world means to forget or maybe worse . . . distort and make light of.

"I'm sure that many people went to their death not even believing afterward that they were dead," Wiesel wrote of the Holocaust.

Utilizing archival footage, interviews both new and old, salvaged photographs, and the blistering animation of Joel Orloff, Soul on Fire is a biography of a teen survivor of the concentration camps who when freed refused to weep: "We didn’t cry maybe because people were afraid. If they were to start crying, they would never end."

Wiesel, who died in 2016, was a winner of the 1986 Nobel Peace Prize for his defense of human rights and his crusade to prevent the Holocaust from being forgotten through his plays, 57 books, and teachings. Describing himself as "a storyteller, a teller of tales," not unlike the Ancient Mariner, his journey's end is still far in the future, as this documentary proves again and again.

Phinehas Veuillet's Neither Day Nor Night focuses on the Gabais, a French family of Sephardic heritage, who have resettled in Israel within an ultra-orthodox Ashkenazi community. For the uninitiated, this could be a cause of some tsuris.

Ahuva (Maayan Amrani), the mom, has gone whole hog with the religiosity. The only remnants of her wild, bare-midriff youth are snapshots hidden in a cardboard box under her bed. Her once flowing locks are now concealed in a tightly wrapped headscarf. Her smiles are now fleeting and forced.

Shmuel (Eli Manashe), the dad, spends his days renovating apartments, apparently an unorthodox vocation. He also embraces his Judaism, but his dress, prayers, and temperament avoid the severe restrictions that his wife embraces. Spin-off: trouble on the mattress leading to sleepless nights.

The center of this story, however, is the bar-mitzvah boy, Rafael (Adam Hatuka Peled), the couple's oldest son. The lad is a brilliant scholar, the best in his Talmud Torah class, which should easily earn him a spot in the best Yeshiva in town, but it's not to be so.

The headmaster, Rabbi Shimon, who teaches that true scholarship brings its just rewards, will betray his own precepts. There is only one opening at Rafael’s preferred Yeshiva for a Sephardic student, and the good rabbi allows a dull-witted youth with a rich dad to weasel his way in.

So where will all this unkosher hypocrisy lead? Well, what you expect from life? A little tragedy, some shopping, a rethinking of past joys, a lot of prayer, some geschrei-ing, and an unanticipated finale. With fine thesping throughout, especially from Peled, a bubbe’s dream with his sorrowful eyes and pinchable cheeks, Neither Day Nor Night, described by an Australian festival as a “crime-thriller,” is a pleasing tale of overcoming adversity in an unsuitable manner.

Moving back in time once again, Annette Insdorf, in her classic Indelible Shadows: Film and the Holocaust, wrote: "Filmmakers and film critics confronting the Holocaust face a basic task—finding an appropriate language for that which is mute or defies visualization. How do we lead a camera or pen to penetrate history and create art, as opposed to merely recording events? What are the formal as well as moral responsibilities if we are to understand and communicate the complexities of the Holocaust through its filmic representations?"

Writer/director Yoav Potash seems to have the answers with his 13-minute short "A Great Big Secret." The film opens in October of 2023 with Anita Magnus Frank standing by a screen, clicker in hand, addressing a group of attentive San Franciscans: "I am a Holocaust survivor. I survived the war as a child in hiding. I lived under a false name."

Born in 1936 to an Orthodox Jewish family in the Netherlands, Ms. Frank had an ideal childhood, and the photographs prove it: "My father adored me, and by his description, I was a bright, delightful child. I was also a tough little girl."

But then Hitler invaded her wonderland on May 10, 1940. At this point, this teller of tales morphs into an animated white-line drawing on a black background, the only color being the yellow Jewish star she must wear. Worse, at the same time, her Jewish classmates began disappearing one by one.

Finally, one morning, her family was forewarned that unless they wanted to wind up in a concentration camp, that night was their last chance to escape the fate of their Jewish neighbors. "I remember my mother saying to my brother and me, Anita and Norman . . . you're going to go and live with a family that you don't know. . . You never will tell anyone you're Jewish, or you will die."

"I lived in constant fear, and I learned to hide my Jewishness," Ms. Frank admits. Then, from that first shelter, she was moved to a farm where a group of boys sexually violated her multiple times. She submitted out of fear of being exposed. Weeks passed, and she was reunited with her mother; the Americans showed up, and the war ended only to expose that post-war anti-Semitism had flourished among the gentile Dutch populace.

Still forced to hide their Judaism, the family moved to the States, and Frieda, at age 16, got a job taking care of a director's brood on the West Coast, gained 50 pounds, went to Harvard, got a job with the Rand Corporation, married, became a mother, and now within her final decades, shares a story again and again. Why become a memory for others?

Mr. Wiesel once noted, "Without memory, there is no culture. Without memory, there would be no civilization, no society, no future."

What survives longer than a memory? Buildings, of course. Just ask Ada Karmi-Melamede, the subject of her daughter’s unflinching documentary, Ada: My Mother the Architect. As a voiceover notes: "She is the Madonna of Israeli architecture."

Ms. Ada, who's designed Jerusalem’s Supreme Court building, Ben Gurion Airport, and the Open University of Israel, is, at times, a slightly prickly soul who, after not receiving tenure from Columbia University, packed her bags and moved back to Israel, taking everything she needed with her except her three children and spouse. As she herself notes, "Maybe I'm really not that much of a Jewish mother. I have never really worried about you."

Catch the look on her daughter's face when Ms. Ada shares that. It’s priceless.

Well, she wanted a career and not to be stifled, and she succeeded. Now in her 80s, she is considered "one of a group of architects who built Israel from the ground up." Some of her mottos for designing: "The feet look for the shortest dimension. The eyes look for the longest." "Today, there are buildings with no art." "Architecture is not necessarily about harmony."

Talking about harmony, Ms. Ada is a bit distressed with the leadership of her country's leadership, which she calls "a bad dream now." That aside, for anyone with an affinity for a career involving light, glass, stone, and chutzpah, this is essential viewing.

As essential as Joan Micklin Silver's 1975-Oscar-nominated Hester Street. Yes, it's been 50 years since Carol Kane taught herself Yiddish to play Gitl, a young woman with a child who travels to New York City to join her very Americanized, now philandering, husband Jake (Steven Keats).

Can the head-scarfed Gitl win him back when she speaks not a word of English? Plus, her attire and stance are totally Eastern European. It's not sexy for this man who once loved her and is now ashamed of the same.

And what about her boy Yossele, whom Jake's renamed Joey? Will he soon distance himself from his "Momala"? Well, Dad snips off his payes while Momma puts salt into his pockets to ward off the evil eye whenever he leaves the apartment.

So you're asking, "What chance do centuries-old traditions have in the New World?" Who am I to tell you?

Discovering who wins is the delight of this beautifully textured recreation of a time when being an immigrant had its challenges, although winding up in Guantanamo was not one of them.

As for you TV bingers, don't feel left out. There are six award-winning episodes screened of German TV's answer to Dallas, The Zweiflers. Imagine that the Ewings were uncommonly Jewish, lived in the Düsseldorf of today, and instead of owning an oil company, they dealt with pastrami and potato salad.

Yes, there are four generations of Zweiflers, from concentration camp survivors to deli entrepreneurs to chronic kibitzers, each embracing their Judaism in a distinctive but overlapping manner. One might use ketamine and paint surrealistic group family portraits that are a bit graphic. Another might fall in love with a lovely Caribbean chef who's anti-circumcision." A third might insist: "Only money can free you from the ugliness of the world . . . . A defenseless Jew is a dead Jew."

And how's this for a marital chat?

Husband to his kvetching wife: "Isaac Beshiva Singer once said, 'Life is God's novel. Let him write it."

Kvetching wife: "You're trusting in God? When did he last help us?"

She later brags to her hubby, who suddenly wants an open marriage: "I never had an uncut penis in my life."

With a first-rate cast, a stunning male lead, an often-hilarious sendup of Jewish stereotypes, blackmail, a mohel, plus platters upon platters of delicious edibles, the Zweiflers never forget for long that even in the Germany of today, especially in the Germany of today, they are seen always as Jews.

Without a doubt, this festival is a tribute to Primo Levi's words: "The injury cannot be healed. It extends through time."

(Presented by the Jewish Museum and Film at Lincoln Center, the films for the 2025 New York Jewish Film Festival (January 19-29) were astutely selected by Rachel Chanoff, Founding Director, THE OFFICE performing arts + film; Lisa Collins, director, writer, special correspondent, programmer, and events/film producer; and Aviva Weintraub, director, New York Jewish Film Festival, the Jewish Museum; with assistance from Cara Colasanti, film festival coordinator, the Jewish Museum.)