A man wakes up in a cheap motel room. A woman lays next to him bathed in blood. He tries to wake her but she’s dead. He can’t remember what happened but does recognize her as the half naked woman who knocked on his door earlier, claiming to be pursued, and ran into the bathroom.

We are clearly in Film Noir territory.

Over the next 100 minutes or so, the intriguingly titled Cinema of Sleep will switch us back and forth between past and present, terror and regret, substance and style. We’ll track the man’s effort to vindicate himself. But hey, he’s on his screen too: in a cutaway, we see that the man sits in a darkened movie theater, watching himself waking up. Shadowy figures surround him and accuse him of murder. As they lead him out, the man pleads for someone—anyone—in the audience to help. But everyone in there is asleep in their seats.

Cinema of Sleep takes place mostly in that motel room. It’s the tale of refugees. The man, Anthony, is from Nigeria. He’s looking for a job, planning to bring his family to the US. He and his children are inveterate movie-goers. He assures them, “I will be invisible, but you will feel me in the cinema.” He speaks with them by cell phone when the reception is good, but they have their own problems and appear to be in imminent danger (when reception is poor, he rants: “This is America! I thought you always had cellular service!”). The woman, Abrihet, is escaping an abusive marriage. She’s from Ethiopia, an immigrant like Anthony. They are “stuck between two worlds,” she tells him.

Cinema of Sleep is in black and white, its aspect ratio, or screen shape, a tight square that confines the action and heightens the claustrophobia. Its handheld camera recalls Cassavetes’ Faces in some places, Ulmer’s Detour, even Lynch’s Eraserhead in others. Its characters bring up Casablanca and The Maltese Falcon, and its credits are superimposed over Charlie Chaplin’s 1917 film The Immigrants. And don’t forget the nod to Herk Harvey. An old TV set in the room is propped on a chair and tuned to a channel that shows silent movies.

Cinema of Sleep comes from writer/director Jeffrey St. Jules, whose other features include 2014’s Bang Bang Baby and 2024’s The Silent Planet (Cinema of Sleep was made in between those, in 2021, but is only now available on VOD). Mr. St. Jules made his bones as who The Globe and Mail has called “Canada’s master of the surreal short form.” In this film, Jordan Oram’s cinematography and Dev Singh’s editing are crucial to the aesthetic vision.

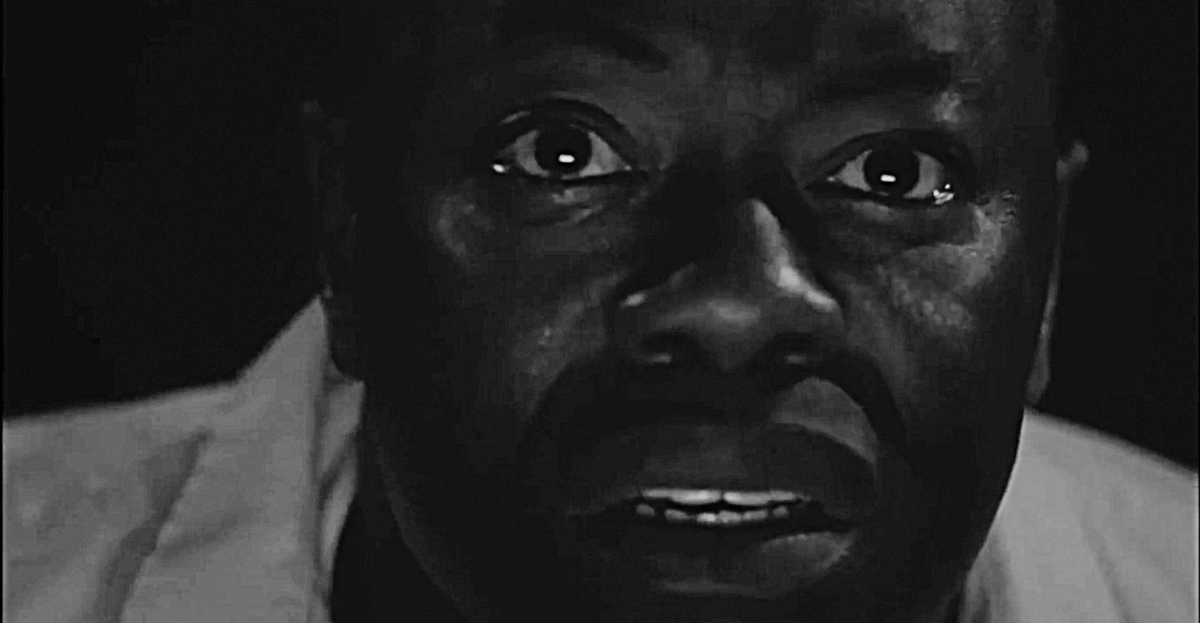

As Anthony, Dayo Ade commands the screen (the filmmakers know the visual impact of a very dark-skinned man in a very bright white shirt). He runs the full range of emotions, and his performance is intense and nuanced. Getenesh Berhe is an able foil as Abrihet, the woman of mystery, whose distress turns to warmth. The pair’s relationship grows and anchors the film, especially in their extreme closeups while recounting their pasts. Other notable cast members include David Lawrence Brown and Felix Montogomery as seedy detectives, Olunike Adeliyi as Anthony’s wife, and Jonas Chernick as Anthony’s neighbor Frank, a hipster who knows the score.

Speaking of scores, composer Darren Fung channels Bernard Herrmann, providing lush music that would make Hitchcock proud.

Cinema of Sleep touches on dislocation, family, connection, the illusion of film and its restorative power. The good news is that while it echoes other films, it does so with depth and affection. Cinema of Sleep is not just a genre exercise. It’s bold and original.

__________________________

Cinema of Sleep. Directed by Jeffrey St. Jules. 2021. Available on VOD. Runtime