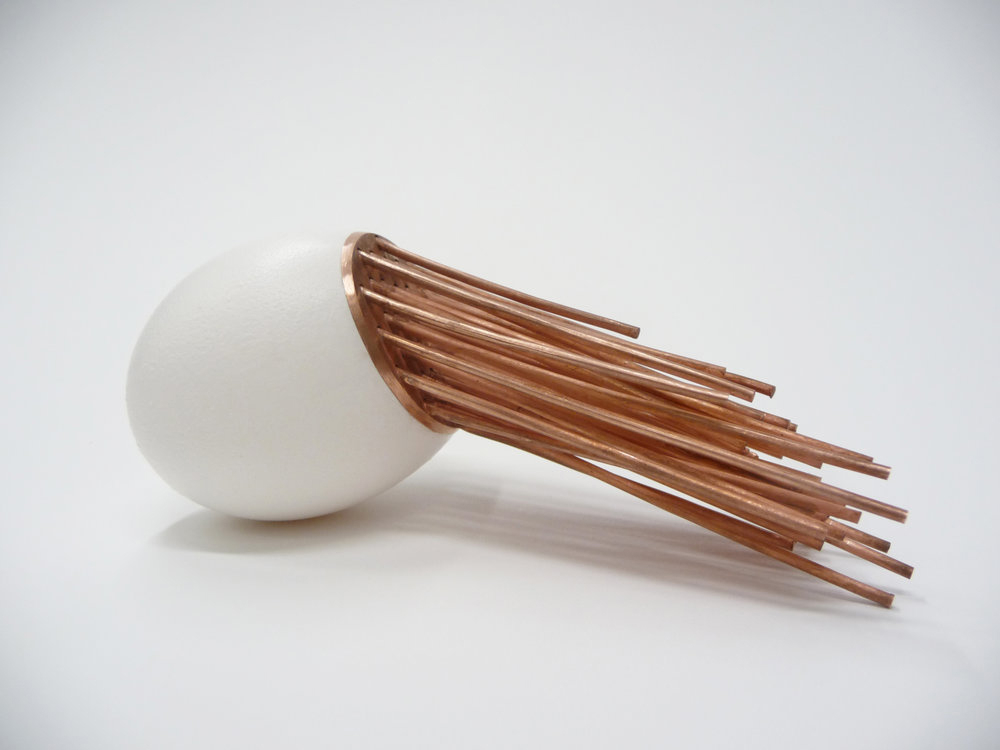

Image 1: Jaroslava Prihodova, Home Made (2015), stainless steel, bred, 8 x 2 ¼ x 2 3/8 inches (photo: courtesy of the artist)

Raised in Velký Šenov, in the Bohemia section of the Czech Republic, and currently living in Cortland, New York, Jaroslava Prihodova's life has truly been a tale of two cities. Growing up in a Communist state, with her parents, an aunt and uncle and her grandparents, Prihodova has largely happy memories of those early days. The bucolic setting of her childhood home, that was situated next to a fruit orchard and a vegetable garden, and where chickens and rabbits were raised, the young Prihodova saw life as wholly sustainable and quite secure. On the other hand, there was always that overriding system of order and intolerance for the West imposed by the totalitarian regime that brought change and inspiration to her thinking later in life.

Her art today, can be seen as a compelling and curious blend of what is considered to be the unfortunate divide between fine art and functional design. At times, Prihodova also employs humor while challenging her viewers to think creatively, with the desire to expand preconceived notions of the separation of form and function. I recently had the opportunity to ask her a few questions that I hope will shed light on her complex, and very pure vision about the marriage of art and design.

DDL: Having never lived further than 25 miles from my birthplace in the Bronx, NY, it is hard for me to imagine the personal mental and physical upheaval that would follow a move from Central Europe to upstate New York. Even given the fact that you have considerably more freedom in the U.S., and having left a country that has Soviet oversight, there is still a lot of reorienting to consider, let alone a language barrier. In reading about your past history in the Czech Republic, you feature quite a few reminiscences of past experiences that helped mold the artist you are today. Was it the Velvet Revolution of 1989 that effected you most, or is it some far less dramatic universal change? Or maybe, was it something far more personal such as the time spent with your grandmother, who really seemed to be the matriarch of the family?

JP: Yes, it was a culmination of factors and realities that impacted the angle from which I view the world. As you alluded, my life took an unexpected trajectory when I moved to the Unlined States. In 2002, I was a freshly minted graduate from the Studio of Natural Materials at the School of Art and Design in Usti nad Labem, the Northern part of Czechia. I left everything behind to be with my partner, an American artist I met during my short residency in 2000. After I arrived, I welcomed a period filled with productivity and artistic growth. At the same time, it was a long stretch that was underlined by feelings of displacement and a sense of disillusion. As I spent more time here, a physical and mental distance from my motherland afforded me the ability to evaluate my roots and influences with a certain objectivity. It became more apparent that in contrast to the culture I was trying to understand and adapt to the way I was brought up had everything to do with the way I process my ideas, approach to materials, art in general and also life.

I was in the seventh grade when the Velvet Revolution broke out. Even as a teenager, I understood that the situation was charged with an historical significance and would shape the future in a completely new way. The urgency and the weight of events that followed are permanently embedded in my memory. As one ages, the gift of time passed allows seeing reality (transformed in history), in a broader context, personal as well as cultural. When I see footage from the revolution, I am instantly taken back in time. It is an emotional event. It is curious that I feel similar when I come across documents from an earlier time when I was not even born. I once read that trauma or intense emotional experiences are passed on genetically from our ancestors to new generations. I often think that the human body retains memory and associations, almost like other materials such as paper or metal, that the aftermath, the evidence of distress, is always present. For instance, I recall my reaction visiting the Josef Koudelka retrospective at Getty a few years back (Nationality Doubtful, 2014-15). His political images adjacent to photographs from his series from Slovakia and other included series caused me to hold back tears. I had to leave the gallery several times to compose myself. Although I was not even born at the time these images were circling the world, I left undeniably connected to the content, and I felt like I shared this visceral moment with my parents who were young adults at the time 1968 Soviet occupation occurred.

I hold fond memories of my childhood, my home, and the village where I grew up. As I mentioned, my experiences as a child, my interactions with my parents, and my sister, who are all remarkably creative people and my relationship with my grandmother, imprinted sets of templates through which I view my surroundings.

DDL: It is amazing, how as you can sense that: "…trauma or intense emotional experiences are passed on genetically from our ancestors to new generations." I believe this, too, as I accept the theory of the Collective Unconscious.

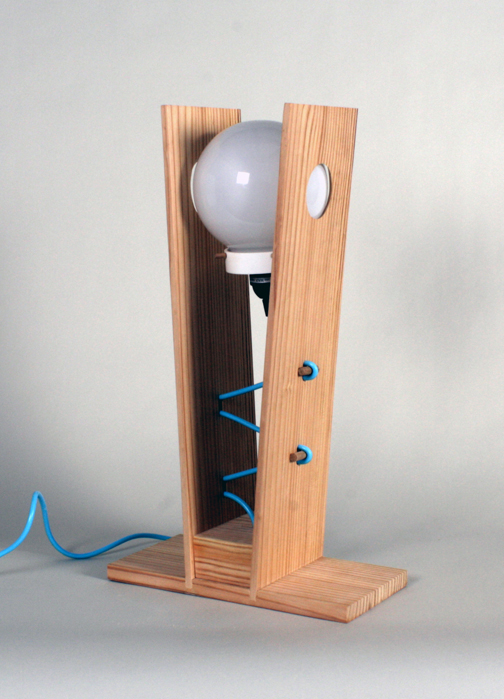

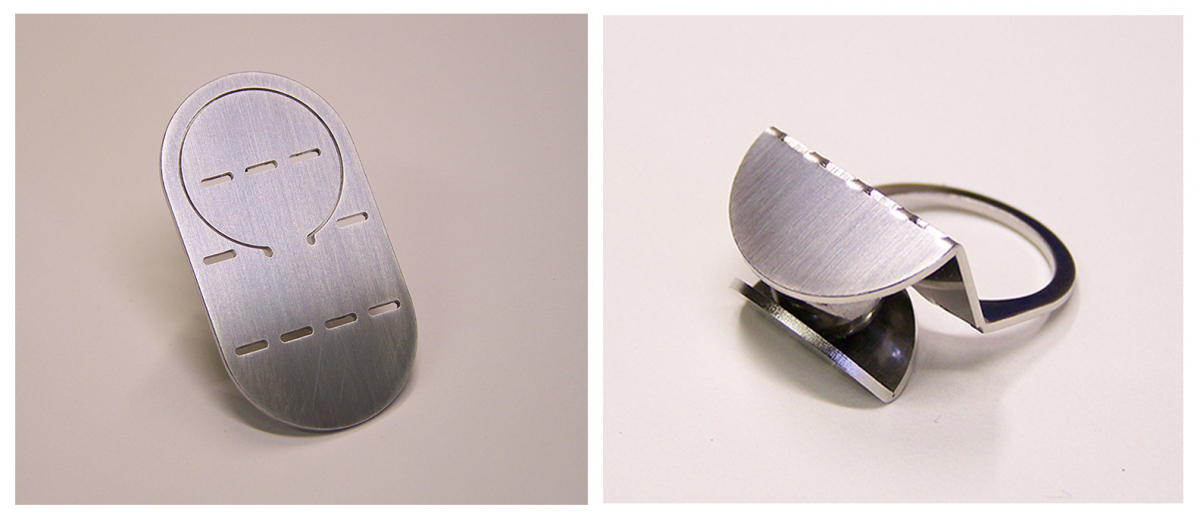

In looking at your Dislocation series of 2016, I see a very palpable visual weight coming across. You mention on your website "the expulsion of the German population from Sudetenland after World War II," and how the ensuing vacancies of the homes must have affected your grandfather Ladislav upon his return in 1946. That history very definitely haunts the Dislocation series. Then I look at your Vase from 2010, the Planes and Table Light of 2015, and your design sense applied to the Vklad Series, a ring created in 2012, and I see so many contrasting elements, yet they all somehow relate. Perhaps it is the directness you take to the narrative or the forwardness of the function, mentally and physically, that ties everything together. As Federico Fellini is quoted as saying: "All art is autobiographical; the pearl is the oyster's autobiography." On the other hand, one can also be of many minds. Which is most true for you?

JP: My practice as an artist evolved from mostly formal considerations (aesthetics, use of materials, execution, scale, function, etc.) into a field of deeply personal themes solidified out of the pulp of memories and experiences in the framework of historical amnesia. With the Dislocation series, I let my work break free from obligatory principals and self-inflicted rules, allowing ideas to expand into a contextual narrative. This project is a personal attempt to come to terms with a troubled historical event, with consequences imprinted onto my family legacy. The work challenges the notion of a forgotten collective past, an unresolved political conflict filtered through my experience as someone who is permanently yet voluntarily dislocated from my homeland. Upon reflection, it is also important to acknowledge that the series was conceived here, on stolen land, in a place where I settled. So, how do we resolve the inner conflict with history? Is it possible to surrender to reconciliation instead of letting one be hindered by the burden of tragedy? I believe one can start with an acknowledgment.

I often try to imagine what it was like, starting life over in a new place and physically rewriting history. It is difficult to imagine what my grandfather must have felt when he arrived at this unfamiliar site, and moved into a home that was formerly occupied by a German family, filled with personal artifacts that only echoed a vibrant life. I never had a chance to speak to him about his experience since he died long before I was born. I can only speculate, but my instinct tells me that the prevailing sentiment centered on responsibility for his family. However, I think the place where everything was lost for the family that abruptly departed his home prior to his arrival left a lasting impression.

You mentioned the other side of my practice. I don't divert from my work methods too much when I produce objects with utility. Design has always been an interest. I studied the design of lighting for four years, and I adopted some of the principles of art in general. Both art and design are rooted primarily in communication. I was fortunate to study in institutions that were largely built on the legacy and philosophy of modernism. Bauhaus's educational principals were undeniably present in my schooling. Although there are some apparent differences between art and design, I'd like to consider them as twins. One of my favorite designers is Dieter Rams. His ten commandments for good design can apply to both aspects of creative practice. In my opinion, one cannot exist without the other, as Bruno Murani said in his book, Design as Art: "The designer is therefore the artist of today, not because he is a genius but because he works in such a way as to reestablish contact between art and the public, because he has the humility and ability to respond to whatever demand is made of him by the society in which he lives, because he knows his job and the ways and means of solving each problem of design. And finally, because he responds to the human needs of his time, and helps people to solve certain problems without stylistic preconceptions or false notions of artistic dignity derived from the schism of the arts."

My ultimate objective is the simplicity of form and function while employing the least amount of materials and manipulation. I believe that it is quite a challenging task in both art and design. A good example is a laser-cut stainless steel ring titled Fold (2010). Inspired by origami, the approach illustrates how to utilize material with minimum waste, transform a flat surface, introduce volume, tension, intentionality, and the perception of size and scale.

DDL: The creativity you show as a curator is as profound as your own artwork. At this time we are speaking, you have Measured Confluence on display at the Dowd Gallery at SUNY Cortland. As the curator of this exhibition, it is your desire to show how art influences science and science influences art -- and where they meet is the purity of design, as function and form coalesce. I imagine this show has been a great experience for the artists and the students to share.

First, what inspires your curatorial process, and finally, what is most important for you to project in all of your professional practices?

JP: I consider curating as another facet of my practice. It is an opportunity to think about art outside of my work, and to be creative in a specific way that does not involve my personal approach to making art. I am fascinated with the process of finding connections in places where they might not be evident to others. Vladimir Nabokov wrote, "There is no science without fancy and no art without facts." My primary focus is to develop impactful exhibitions that reflect and honor the diversity of thoughts, art concepts, and the people who create them. My objective is to bridge art with other disciplines to provide a broader context for our students and visitors. I want to illustrate that visual art is not an intimidating indulgence that exists in isolation, while linking it to various fields of science and humanities, as I believe that art transcends the ability to communicate disparate ideas across many areas of study. Therefore, the challenge for me is to present programs that are relevant not only to our school but also to our local cultural community and still deepen the intellectual engagement through object-based learning that fosters an appreciation for art and its cultural importance in general. We are a small gallery in a teaching institution, which allows us to be flexible with artists we bring to campus but also with collaborations with faculty members from other departments, schools, and institutions.

Mounting an exhibition is a big job that requires many details to align in a harmonious outcome both conceptionally and visually. That is where both the purpose and purity of design are most visible. The design of the show is something I take very seriously. That is the moment when everything comes together and where artworks live in a conversation with one another. It seems I push against prevailing trends in exhibition design. I prefer a minimal presentation where the work has a place to tell a story. In that aspect, I am a traditionalist.

As someone who navigates both sides of visual arts -- producing and presenting artwork, I strive to propose ideas and forms that might not be obvious on a first glance but somehow reveal themselves in small increments equal to time invested. The reward and impact are always difficult to assess, because all of the artistic aspirations are process-oriented, unfolding over time, and rely on intellectual inquiry. In both practices, I try to emphasize innovation, interdisciplinary investigation, and exposure to cultural inclusion in the world that is continuously in flux.

DDL: In a time of Covid, with shows being cancelled or rescheduled, lives and businesses being turned upside down, and the general way of doing things drastically changing for the foreseeable future -- how have your gallery and studio practices changed?

JP: When we started this interview many months ago, we did not anticipate that the world, not only the physical world but the field of art, could change in a matter of weeks. It is remarkable how much we need to prepare for, adjust, and adapt to. For our gallery, in light of the uncertainty caused by the pandemic, it is extremely difficult to proceed with planned shows, and frankly, justify the financial commitment when there is a good chance that the gallery will be closed on a day's notice. I think it's a common problem that many galleries and museums are facing right now.

I started to utilize a lot of technology to bring our visitors closer to the art we present. I believe that spatial context is still important. That is why I like to continue to install work in the gallery and employ digital tools to substitute for a lack of accessibility. It is interesting to think about new ways to consume and interact with art. We need to establish new modes of interaction between the viewer and the artwork. I see it as a challenge. If I have to predict what will occur, we might reevaluate our relationship with the immediate. Because most of us were forced to work from home for months, we faced the reality of where and how we live. I hope that this fact will emphasize more, how we live and what we surround ourselves with. This shift has the potential to offer a real platform for artists, designers, and architects to improve our living conditions and reevaluate that relationship to art. I find it fascinating and disturbing at the same time.

As for my personal practice, nothing has changed. I proceed with the way I have worked in the past. After all, art production can be a solitary activity that dictates isolation to some degree. In a way, this situation is ideal for artists and creators. The question is how to bring results and outcomes to the audience effectively. Certainly, we have entered a transformative period for the arts.

For more information about Jaroslava Prihodova's curatorial project Measured Confluence, follow this link.

For more information about Jaroslava Prihodova's studio practices go to his website.